In the late 1980s, my friends and I knew something called Dungeons & Dragons existed—and we knew that it was for us. But no shop in our little upstate New York hometown carried the books, and the World Wide Web was still a few years off. We did have a set of the dice, so we worked with the scraps we’d gleaned from related books and video games, crafting rules and settings to help us tell the stories we wanted to tell.

Article continues after advertisement

It was a messy process, but it worked. Over countless weekends and summer nights, we conducted our imaginary characters through marvelous journeys, high-stakes intrigues, and absurd escapades. Tabletop roleplaying games had been around for some fifteen years at this point, but we felt we were tapping into something both mythic and new.

Which is exactly what we were doing. D&D owes its existence to a peculiar mix of ancient legend and folklore, fantasy literature, tactical wargames, and improvisational theater. Now fifty years old, the game is more popular than ever, but what keeps it new is the players who gather with friends to make it their own. Little wonder that so many writers have emerged from these crucibles of unrehearsed storytelling. Holly Black, John Darnielle, Lev Grossman, and others have talked about their early encounters with the game and how it informed their later work.

Recently, celebrated writers including Renee Gladman and Brian Evenson have created original RPGs and adventure modules. I’m particularly interested in D&D as a folk practice for generating stories that are both visionary and ephemeral—and I believe that fiction writers can learn a great deal from that practice.

I consider the rules of tabletop RPGs as a kind of vessel for carrying the inventiveness of childhood play into other parts of our lives.

There are as many ways to play tabletop RPGs as there are tables at which such games have been played. But regardless of their chosen style, most players seem to have one thing in common: an appreciation for the unexpected. The referee of the game, whether working from a published module or an adventure of their own making, may plan challenges for their players—perilous settings to navigate, foes to outwit, factions to confront, etc.

But it’s impossible to anticipate everything that might happen in the course of play. Randomly determined events and encounters will alter the context of a scenario as originally envisioned. Small details established in a previous session may turn out to have unforeseen significance. And most importantly, players will come up with ideas the referee never anticipated. That giant snake you thought the heroes would have to fight in order to infiltrate the evil wizard’s tower? Well, one of your players uses the magic rope she found last week to bypass the snake’s floor and open the door at the top of the stairs, releasing it into the wizard’s study instead.

You can feel it in the air around the table in those moments: the crackle of excitement as you collectively discover, in real time, how the story is going to unfold. But how to achieve that kind of excitement in the typically solitary process of writing fiction? Here are a few approaches.

Leave Room for the Unexpected

Some writers prefer to outline every aspect of a story in fine detail before they begin drafting. I’ve tried at times to be one of those writers, but I always fail. Once I start drafting, I can’t help but change things, scrapping whole sections of my outline in order to accommodate ideas that occur only once I’m fully immersed in the language and flow of the story.

I have come to accept this tension between advance planning and spontaneous subversion of the plan as a positive, even vital part of my process. So instead of trying to plan everything in advance, I leave room for chance, for play. My outlines have grown more porous and more open to restructuring. In particularly desperate moments, I might even turn to a word chosen at random from the dictionary, to introduce that sense of the oracular provided by a game’s dice and random tables.

Here’s another technique, borrowed from RPG tools: in addition to an outline (or in place of one) write yourself a long list of words relevant to the story you want to write: images, feelings, themes, whatever has the gears turning. Then occasionally consult your list as you write, combining entries at random to see your ideas in fresh context or with new twists. It can feel a bit like opening a secret door you’ve only just learned is there.

Collaborate with Yourself

The story may exist outside of you, but it doesn’t exist without you. Honoring its will is honoring the part of your brain in which the story has taken up residence. This process can lead to richer, more compelling characters, because they are often the recipients of the control you cede to the story.

When running a tabletop RPG, the referee typically assumes the task of describing the world and its inhabitants, while the players take the parts of the main characters. The fiction writer is cursed with too much knowing, with having to perform the labor of narrator and protagonist both. But once we know our characters well enough—know their backstories, their loves and fears and wants—they may seem to act on their own.

We can also embrace inconsistency, letting characters surprise us by surprising themselves. Giving them space to act out, to push against our plans for them, can reveal new facets of who they are, and also save the story from the tedium of the expected. It’s a way of collaborating with ourselves.

The shared dreaming of tabletop RPGs have acted as the bridge between play and literature.

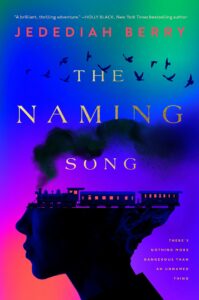

When running tabletop RPGs, great moments often come from putting the characters in trouble for which you do not know the best solution. The same can be done in fiction. In my new book The Naming Song, one of the main characters—a doppelganger of the protagonist’s sister—finds herself in a moment of crisis, emotional and physical, near the end of the book. When I wrote my way to this juncture, I was also writing the character into a corner. I did not know how or whether she would escape. The choice she ended up making—and what it cost her and the other characters—struck the story like a lightning bolt. It’s now one of the most important parts of the novel, and I didn’t see it coming until it was already happening.

Remember Play

In a 1983 interview with The Paris Review, Julio Cortázar talked about the importance of play in his work. “When children play, though they’re amusing themselves, they take it very seriously…Literature is like that—it’s a game, but it’s a game one can put one’s life into.”

I consider the rules of tabletop RPGs as a kind of vessel for carrying the inventiveness of childhood play into other parts of our lives. There are countless ways to access that sprit of serious play in our fiction as well, sometimes in the very structures we choose. Formal games like those Cortázar deployed in his book Hopscotch is one example. More recent game-like works include Peng Shepherd’s All This and More, a novel featuring branching paths for the reader to choose from, and GennaRose Nethercott’s Lianna Fled the Cranberry Bog, a story told in illustrated fold-up paper fortune tellers.

For me, the shared dreaming of tabletop RPGs have acted as the bridge between play and literature, between the promise of endless adventure and the endless demands of storytelling as craft and vocation. Sometimes writing is a less lonely process as a result—I can almost hear the exclamations of my friends, and feel my surprise joining theirs, as the story confronts us with some new facet of its many-sided wonders.

__________________________________

The Naming Song by Jedediah Berry is available from Tor Books, an imprint of Macmillan, Inc.