In 2006, director Richard Linklater made his first foray into science fiction with a film adaptation of “A Scanner Darkly,” the 1977 novel by Philip K. Dick. Dick’s original story delved deeply — and with first-hand knowledge — into the bleak world of drug addicts. Dick has spoken frankly about his drug use, and one can see his paranoia caused by psychedelic drug experiences influencing his work, specifically in novels like “VALIS” and “The Transmigration of Timothy Archer,” but they are most explicit in “A Scanner Darkly.” In the future of the novel, the protagonist is addicted to a hallucinogen called Substance D, and there seems to be no workable social system in place that is capable of solving widespread drug use in America.

Linklater’s film version of “A Scanner Darkly” was made 29 years after Dick’s story was published, but the themes remained depressingly relevant. The film takes place in the future of 2013 after America has essentially lost the War on Drugs, and 20% of the population is now addicted to Substance D. The government claims to be rooting out dealers and growers of Substance D, but the unreliable protagonist — an undercover vice cop named Bob Arctor, played by Keanu Reeves — suspects that his bosses might be involved in the drug’s manufacture. Bob, however, finds that being addicted to Substance D is harming his ability to analyze the situation clearly.

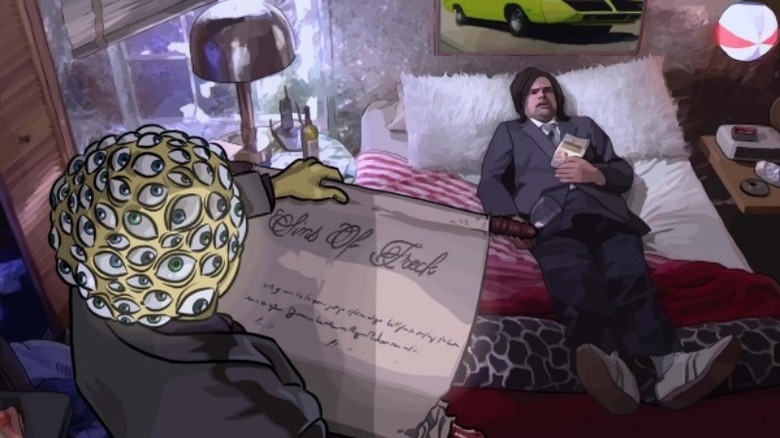

To accentuate the unreality of Bob’s life, Linklater presented “A Scanner Darkly” in a shimmering, vibrant, rotoscoped animation, meaning he filmed his actors in live-action, then hired animators to hand-draw directly into the film, giving the entire movie an off-kilter, wiggly appearance. It has the dizzying, hyperreal look of being high and/or hung over. It’s a gorgeous, fascinating film.

A Scanner Darkly’s rotoscoping fit perfectly with Dick’s creative vision

Most of “A Scanner Darkly” takes place in a relatively recognizable world. Indeed, Bob seems to inhabit run-down homes, overgrown urban fields, and dingy strip malls. The animation isn’t designed to make those things look more dynamic and textured, but rather hazy and indistinct. We can see the carwash in the background, but it’s an impressionistic version of a carwash. There’s nothing wrong with the world. The world is still boring. But there is something wrong with our eyes.

Linklater’s most impressive use of animation was used to visually realize Bob’s “scramble suit,” an innovative sci-fi invention taken from Dick’s original book. Bob is so deep undercover that even his contacts back at the police station don’t know who he is. To assure anonymity, he and his superiors wear head-to-toe holographic suits that scramble up their clothes and facial features. When he talks to his bosses, Bob goes by the name Fred. The constantly shifting faces of the scramble suits likely took a lot of time and attention to animate, and one cannot look away. And despite how high-tech and strange it looks, the scramble suits look natural, almost bland in this universe. The world of “A Scanner Darkly” lilts closer to a dingy, litigious dystopia than a high-tech futuristic wonderland.

There is also a dream sequence late in the film where the character of Charles Freck (Rory Cochrane) is visited by a hallucinatory judge encrusted with eyeballs. That sort of hallucination is best realized in animation.

More than anything, though, the animation is used to enhance the film’s style. “A Scanner Darkly” is meant to capture the drug-addled state of being slightly disconnected from reality. That way, when the heroes make grand discoveries, they feel suspicious. Is this real, or is this just another paranoid fantasy? Paranoia hangs over “A Scanner Darkly” like a cloud.

Critics had some issues with the movie

“A Scanner Darkly” was a modest production, made for only $8.7 million, which is downright minuscule for an animated feature. Despite the low budget, it wasn’t a huge hit, opening on only 17 screens and grossing about $7.7 million. The film was also beset with technical problems, as the various animation team had trouble learning how to use the software. Also, Linklater was busy filming his remake of “The Bad News Bears” when animation on “A Scanner Darkly” began, meaning he was absent from the process and frustrated with how slow everything was moving. Eventually, the first animation team was fired — the studio literally changed their office locks while they were out at work — and a new team was brought in. The initial budget was supposed to be $6.7 million, but the delays caused it to balloon.

The critical response to “A Scanner Darkly” was mixed. The film currently has a 68% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes, with many criticizing the film’s lack of narrative or thematic focus. Several critics noted that “A Scanner Darkly” was wise to lambaste the directionless punish-everyone tactics employed by the George W. Bush administration during its War on Drugs, but that the conclusions it reaches aren’t hard-hitting or outraged.

Manohla Dargis, writing for The New York Times, noted that the animation actually got in the way of the performances, saying:

“Rotoscoping makes certain sense for a film about cognitive dissonance and alternative realities, though both the vocal and gestural performances by Mr. Reeves, Mr. Harrelson and, in particular, the wonderful Mr. Downey make me wish that we were watching them in live action.”

Note that Robert Downey Jr. was experiencing a lull in his career in 2006, as he was recovering from his own addictions and hadn’t landed his lucrative “Iron Man” gig yet.

A Scanner Darkly wasn’t Linklater’s first rotoscoped movie

The difficulties Linklater encountered during “A Scanner Darkly” must have been especially galling, as it wasn’t his first animated feature. In 2001, he made “Waking Life,” an experimental “walk-and-talk” style movie about dreams and the nature of reality. It was realized using the same kind of rotoscoping as “A Scanner Darkly,” and it is one of the best films of its decade.

“Waking Life” follows an unnamed character played by Wiley Wiggins, who starred in Linklater’s “Dazed and Confused,” as he wanders around a shimmering, dreamlike version of Austin, Texas. Sometimes he engages in conversation, although sometimes he vanishes while random people chitchat. The topics of conversation hover around the nature of dreams and occasionally tilt directly into existentialist philosophy: The late Robert Solomon gives a brief lecture. Noted Texan crackpot Alex Jones appears to scream conspiracy theories. The conversations are never less than fascinating, and the animation is exhilarating to witness. It’s the kind of film one likes to watch over and over just to exist in that dreamspace.

“A Scanner Darkly” might serve as a dark mirror to “Waking Life.” It’s a bleak, cynical film about how there is no escape from addiction, and that a pervasive and indifferent police state only allows misery to perpetuate. It’s a film of mourning, lamenting the loss of the people lost to drugs. It’s not about pondering the nature of reality, but witnessing as reality unravels. “Waking Life” and “A Scanner Darkly” would make a fascinating double feature.

Linklater would return to rotoscoped animation again for the rather excellent “Apollo 10 1⁄2: A Space Age Childhood,” a nostalgic film about his childhood as a NASA brat in the 1960s. That film, however, used its animation to recreate the texture of a 1960s suburban landscape, and only occasionally leaned into dreams and the nature of memory.

Our advice? Watch all three. They’re all good.