When Jennifer Kent was first developing a horror film centered on grief, she kept coming up against folks who didn’t see a future in it. Many objected to her project’s proposed title, which doubled as the name for the ominous monster she’d created as a metaphor for unresolved trauma.

“You can’t call a film ‘The Babadook,’ ” she remembers being told. “That’s crazy. No one will ever remember it.”

Speaking to The Times over Zoom from her native Australia, Kent, 55, is no longer rattled by those early naysayers. They’ve been proven wrong. Her finished 2014 movie, which features a ferocious central turn by Essie Davis as a single mother struggling to stay tethered to her life in the years following the tragic loss of her husband, is returning for a limited theatrical run beginning Thursday.

The rerelease will mark a decade since Kent’s mother-son horror classic first terrified Sundance, earned rave reviews (from the likes of Stephen King and William Friedkin), won a coveted prize from the New York Film Critics Circle and netted more than $10 million in global box office on a $2 million budget.

Esteem for “The Babadook” has only grown — not in spite of its “crazy” name but perhaps because of it.

“I mean, people did say, ‘What a stupid name,’ ” Kent clarifies. “And it is. Like, it’s a nonsense name. But there’s something about him that people remember.”

Kent immediately lights up, as if she were talking about an old friend.

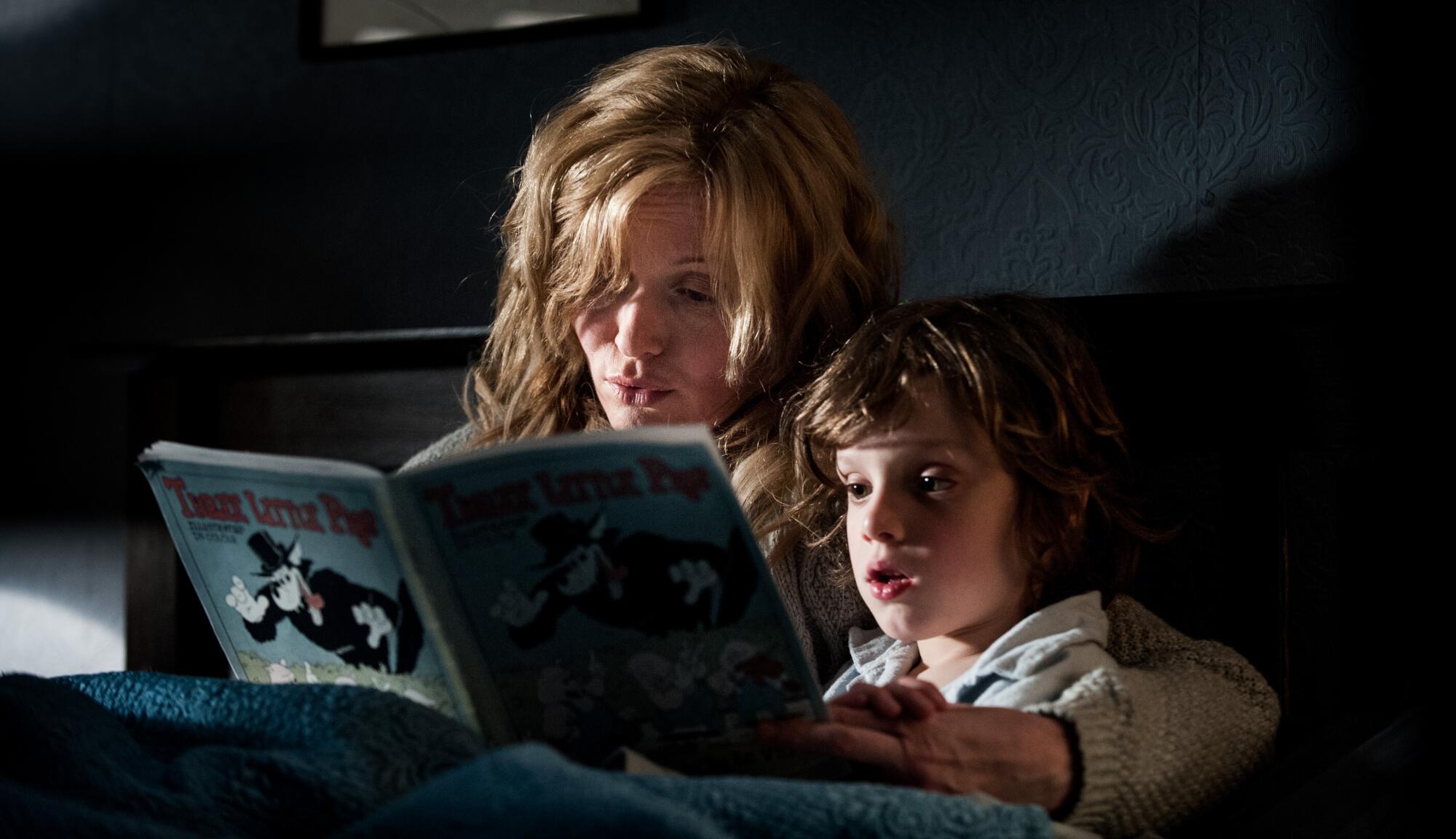

Essie Davis and Noah Wiseman in the movie “The Babadook.”

(Matt Nettheim / IFC Films)

In “The Babadook,” viewers get a first glimpse of who (or what) that titular figure is in the pages of a bedtime book. Born on the same day that his father died in an accident, Sam (Noah Wiseman) is a troubled six-year-old who, by his very existence, irks his chronically sleep-deprived mother, Amelia (Davis). Every night he asks her to read to him. On one particular evening, days before Sam’s birthday — a date that looms large in the life of this lonesome duo — Amelia reads from a book she’s never seen before on the shelf.

“If it’s in a word or it’s in a look,” the opening lines read, “you can’t get rid of the Babadook.” (The nursery rhyme has a decidedly ominous feel.) It’s accompanied by hand-drawn charcoal illustrations that depict a creature with an old-fashioned top hat, a pair of bulging eyes, a matching devious grin and a bulky long coat that hides spindly hands.

“I had just lost my dad,” Kent remembers of the months in 2010 when she first developed “The Babadook.” “So I was really firsthand dealing with grief and the pain of that, just seeing it as a natural process. And I started to think, ‘What if someone couldn’t go through this?’ That came up largely out of some people’s response to me, to my loss. Some people either just couldn’t understand it. Or they were frightened of it.”

The look of the film — and of the Babadook, in turn — came from Kent’s work with illustrator Alex Juhasz, whose sparse minimalism fed into the handcrafted sensibility that Kent, originally an actor, imagined for her feature film debut. Just as she’d done with “Monster,” the 2005 short film which served as a clear predecessor to “The Babadook,” Kent wanted to harken back to the equally playful and nightmarish world of early silent cinema.

Director Jennifer Kent on the set of “The Babadook” with actor Noah Wiseman.

(Matt Nettheim / IFC Films)

“I wanted it to feel like something playing at being human,” she says of the creature. “And when I saw the stills of Lon Chaney in [the lost 1927 silent film] “London After Midnight,” it had that sort of macabre feel. But it was also a little bit hokey. And I thought that was perfect.”

Such simplicity in design, along with a winking sense of artifice, is partly what helped turn Kent’s bogeyman into an unlikely gay icon. No sooner was “The Babadook” becoming a horror classic in its own right that it ballooned into a ready-made meme machine that, by the summer of 2017, found traction within the LGBTQ+ community.

As one Tumblr user put it in a post from October 2016, “Whenever someone says the Babadook isn’t openly gay it’s like?? Did you even watch the movie???” Michael J. Faris, a scholar who’s written on the queer circulation of “The Babadook,” points to that very post as the likely origin for Kent’s film’s embrace within the LGBTQ+ community.

The brazen facetiousness of such viral posts was central to how Kent’s horror film has circulated within extremely online circles in the years that followed. To deny the Babadook’s queer credentials was to deny his very being. Here was guilt being closeted. Here was menace donning a top hat. Here was the suburban family under siege.

Noah Wiseman and Essie Davis in the movie “The Babadook.”

(Matt Nettheim / IFC Films)

“My initial response was confusion,” Kent admits, in between bouts of laughter, as she muses on her film’s unexpected queer legacy. “Then, when it persisted, I thought, ‘Well, there must be something in this, you know? And it’s delightful to me.’ ”

Fans were soon drawing Kent’s hokey monster against rainbow backdrops. They were bending his rhyming schemes to echo contemporary gay lingo (“BABAYAAAAAAAAASS!!!” one illustration read). They were photoshopping his face onto vintage photos of 1970s muscled men in short shorts. At the “RuPaul’s Drag Race” Season 9 finale taped in summer 2017, social media star Miles Jai showed up in full Babadook drag.

“If it’s a meme that was meaningless or someone tweeted about it or whatever, it would have just come and gone,” Kent says. “It would have been funny for a week. But there’s something that’s sticking.”

Kent has since seen her character enjoying a life unlike any she could have envisioned for him.

“I just wrote this really honestly for myself, from a very real place,” she says. “And yes, it’s about grief. But it’s also more about suppression, actually. And what the public is saying is, ‘You can’t get rid of me, guys! I’m here! I’m just going to get bigger and fatter and huger and more menacing if you try and suppress me!’ ”

In the film, he may be all looming shadows and insect-like vocal trills, but out in the wild, the Babadook has become synonymous with a sassy queer figure who suffers no fools: an antisocial, basement-dwelling narcissist who terrorizes young boys for the fun of it. Or, as a “Queer Eye”-inspired skit from the animated spoof series “Robot Chicken” puts it, he’s “a closeted recluse with a penchant for steampunk accouterments.”

Looking back, though, Kent thinks that such irreverence was already baked into how she first promoted the film herself.

“It was all very low-tech during the publicity and promotion for the film,” she recalls. “So I was the Babadook on Facebook. I would log on every day and give people s—. And they would love it. I feel he is a very hilarious character in that way. It was wonderful to play him — and to be him.”

Kent never anticipated “The Babadook” would have such long-lasting appeal. She can’t help but compare such an embrace with the way her follow-up film, 2018’s “The Nightingale,” struggled to find an audience.

“With ‘The Nightingale,’ because it came out in a time where there was so much focus on violence — and certainly violence toward women — I thought that that would be embraced, and yet it wasn’t,” Kent says, with some wistfulness. “It was sort of heavily misunderstood. Very divisive. And I didn’t see that coming.”

Meanwhile, “The Babadook” had an enviable trajectory, from eye-catching villain to social-media sensation and later still to cultural icon. Kent’s film was memeable before such a term had common usage. In time, the Australian filmmaker knows there’ll be plenty more to be surprised about as the film finds younger, newer fans.

“He loves the attention, I can tell you that,” Kent says, grinning, of her wily creation. “He’s lapping it up.”