The Royal College of Art (RCA)’s alumni roster reads like a who’s who of British artists, including figures such as David Hockney, Tracey Emin, Peter Blake, and Chris Ofili. These artists have all emerged from its iconic halls, each significantly contributing to the growth of modern and contemporary art. Emerging from the RCA’s sacred discourse is the promising artist Danny Leyland, a recent graduate of the Royal College of Art‘s painting program.

Leyland’s practice is a coalescence of expressive forms, where the alchemy of painting and the intricacy of drawing meet the layers of printmaking and the mighty power of pen. This multidisciplinary approach fuels his creative engine and lays a solid foundation for what promises to be an eminent career for the emerging artist.

At heart, Leyland is an artisan, a true painter’s painter. Working in the tradition of figures in landscapes, Leyland’s eye of inspiration is his connection to the blanket of Mother Nature, memory, and the chronologies of the ancient past.

For Leyland paintings begin from his initial drawings, sourced imagery, and even film stills. From here, Leyland teases out his account, as the artist states, “build a world into and around the image,” often portraying these findings in works organised by series.

Image courtesy of the artist

I’m interested in finding the moment just before something is about to happen. That frozen second before the embrace, the silence before the mushroom cloud envelopes everything

Danny Leyland

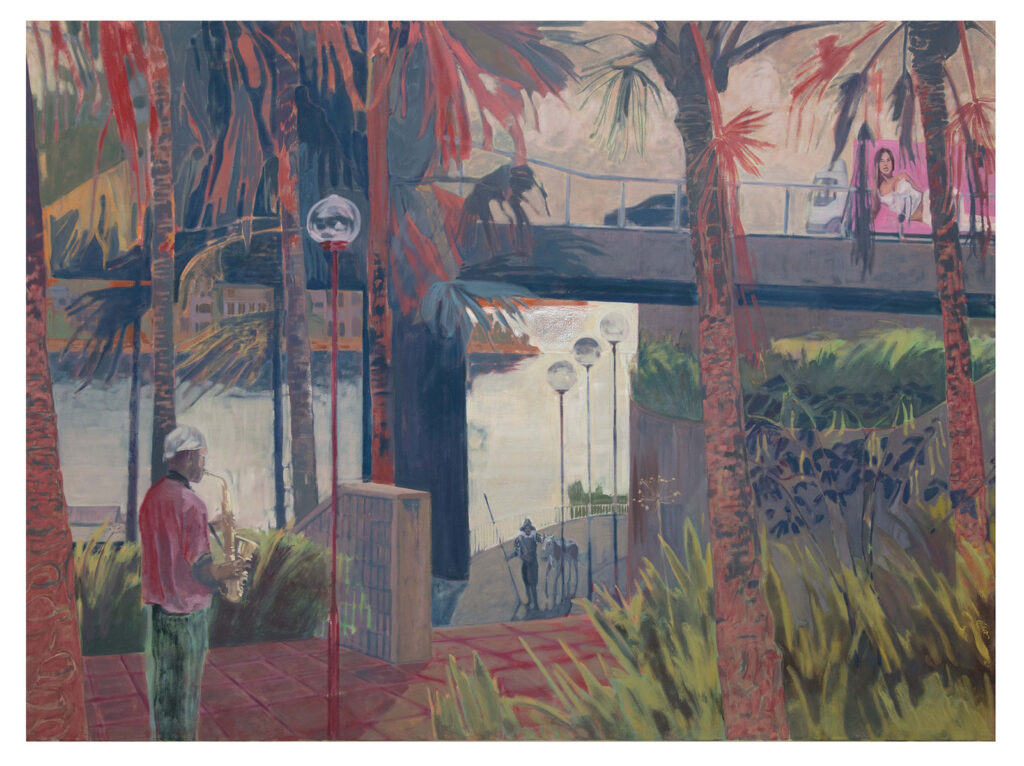

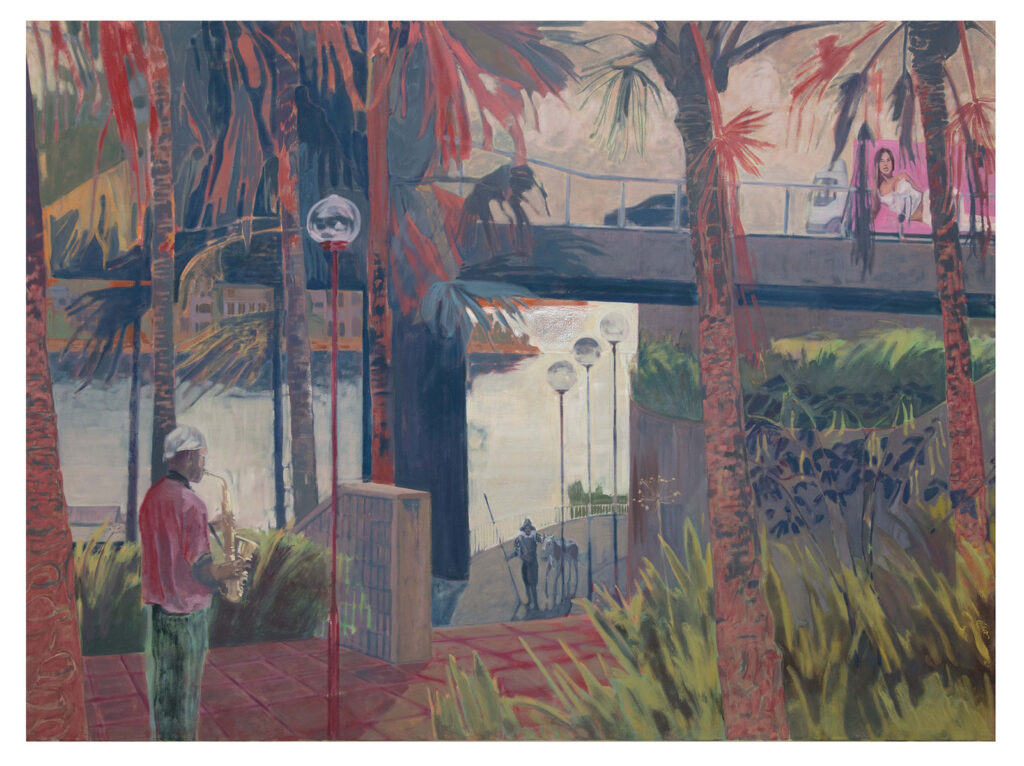

In his ‘Commonplace Dramas‘ series, Leyland tackles the mundane experience, revealing the quiet tensions and unspoken emotions that underlie our daily lives, accentuating these moments of drama with a surrealist perspective, emphasising their emotional and psychological effects.

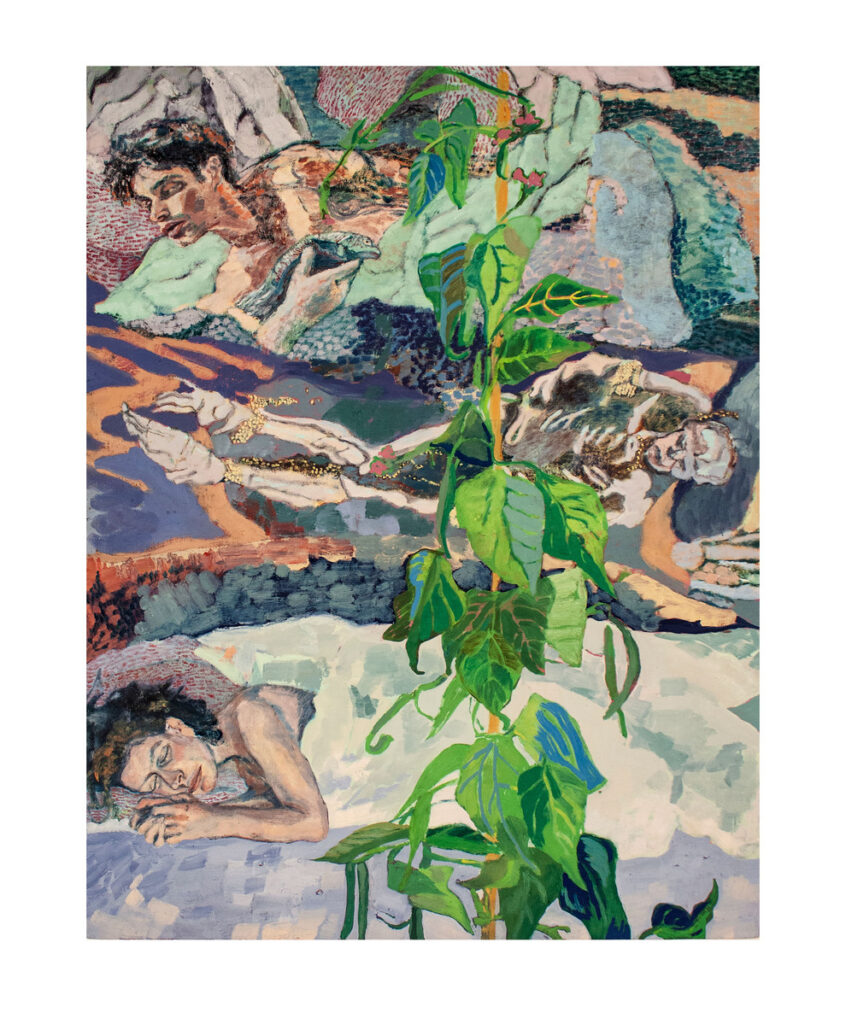

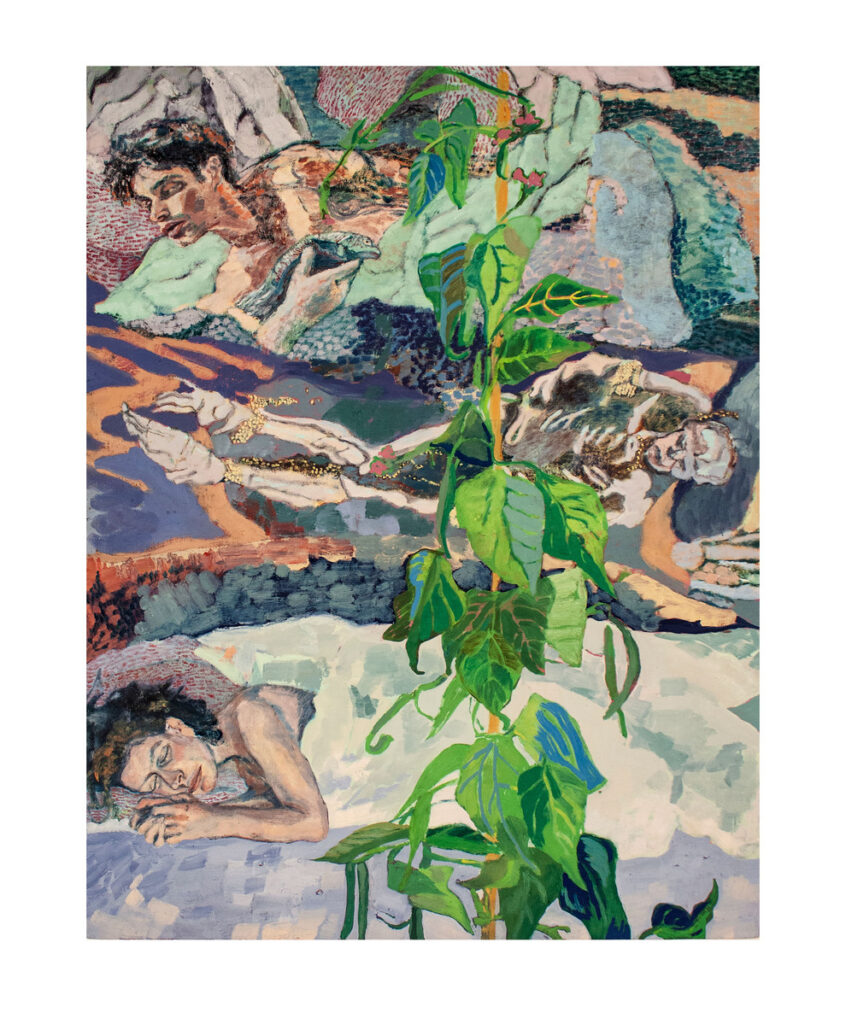

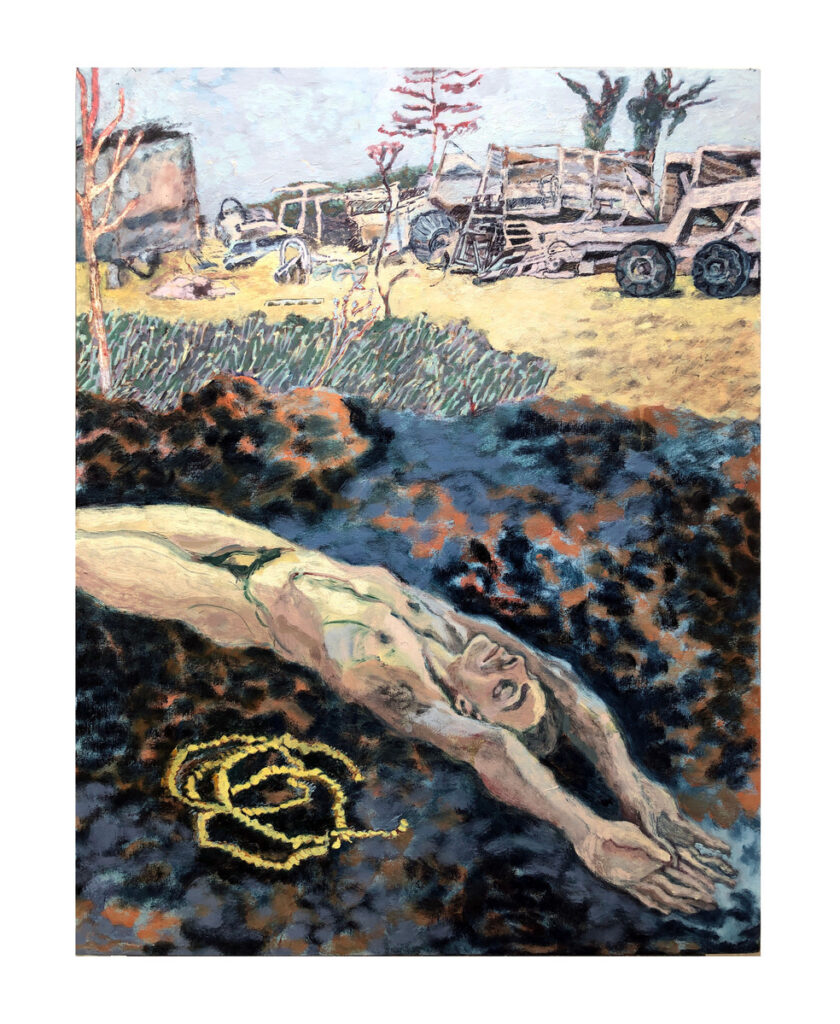

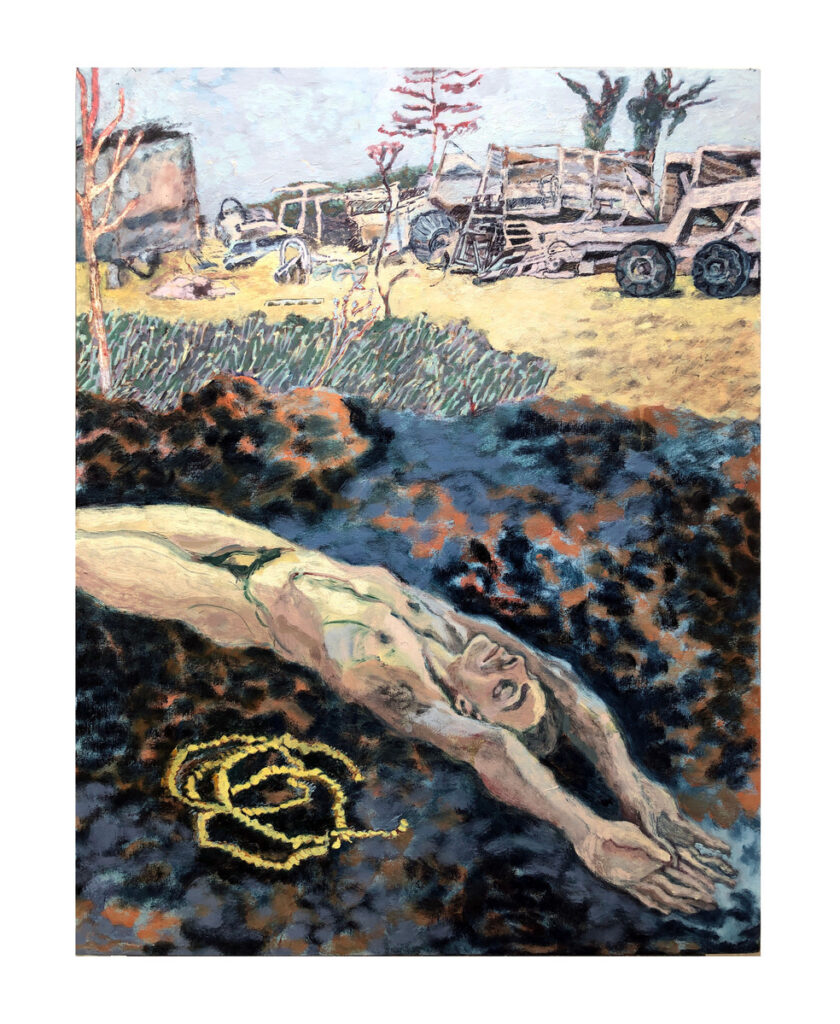

Then we have his burial paintings, a sombre yet intriguing take on a morbid subject. Leyland’s series dives into the dark peril of human fate with unconventional depth, examining his relationship with the dead and the buried, exploring themes of belonging and connection to a place, the last place of rest.

A piece from this series, “Pearly King,” depicts an almost dreamlike situation, showing three figures seemingly sharing a grave, like three in a bed, in various states of repose. Interwoven in the composition are two humans meticulously detailed by Leyland: one gently sleeping, while the other is awake, holding what appears to be a fish. In the middle of the layered composition is a decomposing skeleton, with pearls scattered across parts of its figure, with a green plant running through the layers of earth of the shared bed of death. Through this series, Leyland offers solace, stirring introspection into the shared mortal understanding of the final aspect of permanent rest.

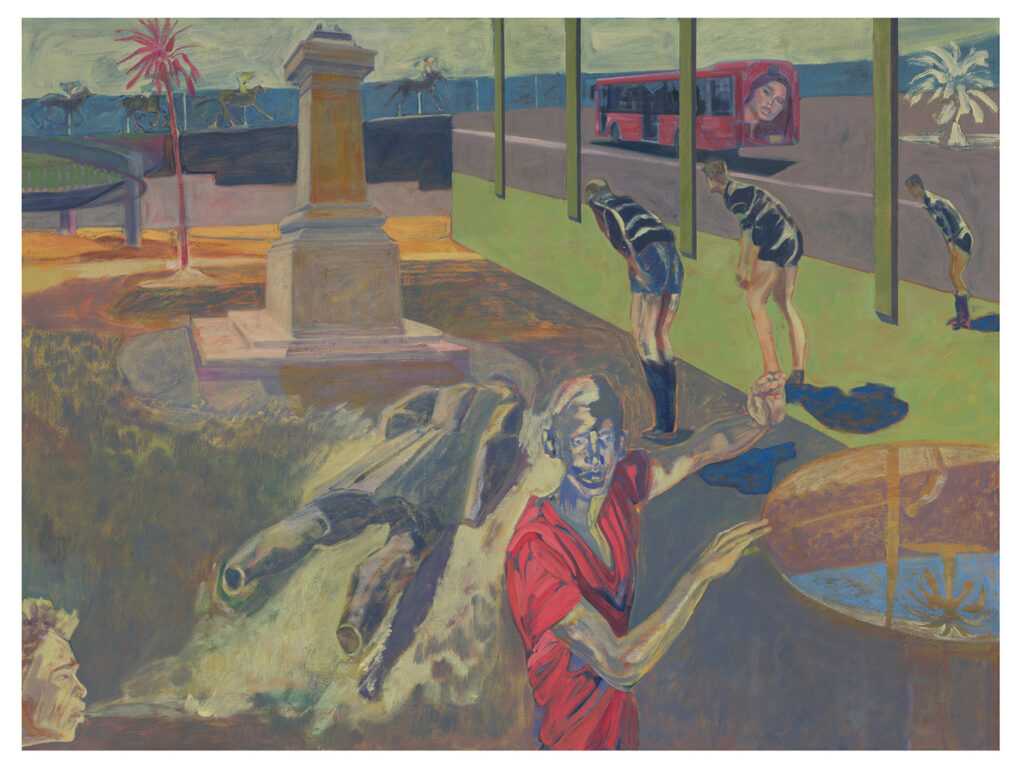

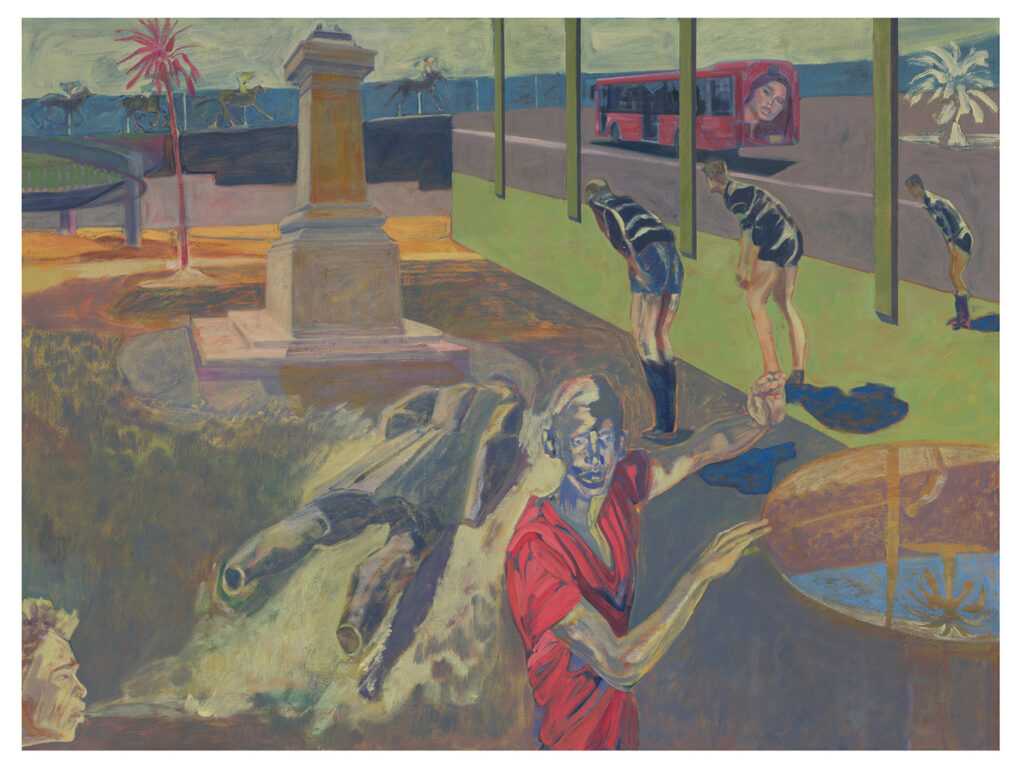

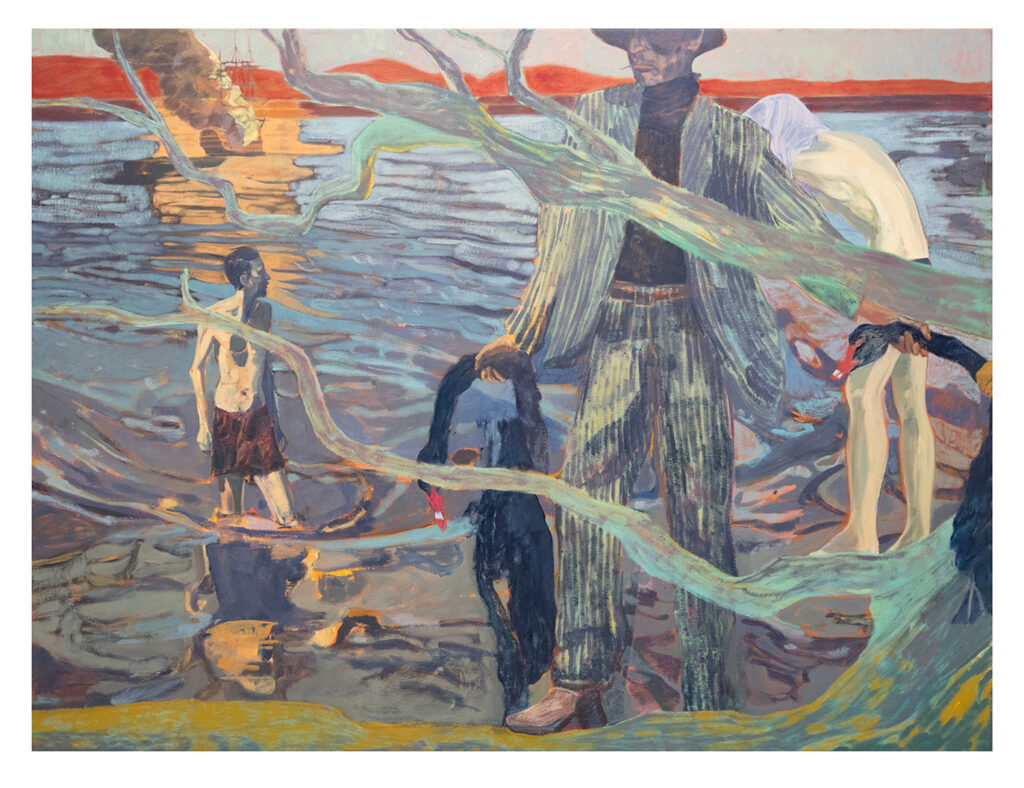

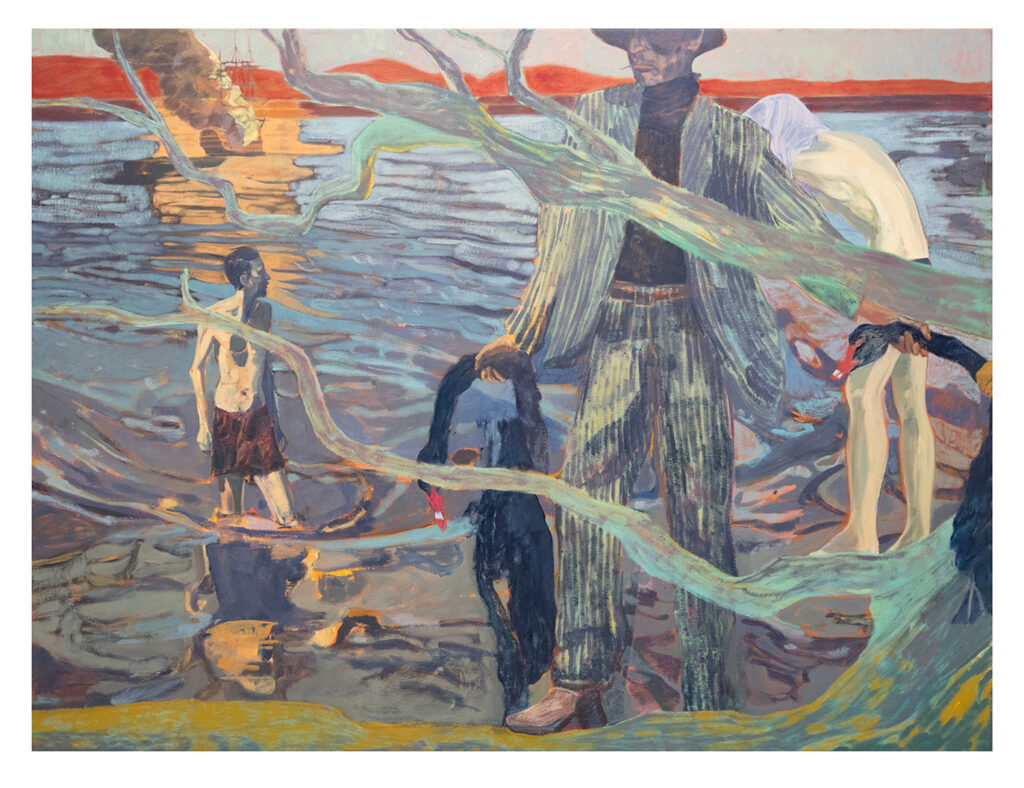

In his latest work, part of his “Predecessor” series, Leyland reaches deep into stories of the past as he approaches the unstable, conflicted, and often bewildering nature of colonialism in an articulated exploration of form, colour, and narrative.

In his piece “Pride of the Vanquished,” Leyland unfolds a socio-political critique of the collapse of authority. At first glance, we see the stamp of power structures dethroned from the plinth it once occupied, capsized by what appears to be the gust of new ideas from a nestled youth. Juxtaposed against rugby players bowed in a position of fatigue or defeat, this adds a coating of realism to Leyland’s otherwise surreal depiction.

A passing bus displays a surreal portrait as it moves along the street, introducing an uncanny element that blurs the lines just a little bit further. Leyland’s critique is dominated by a figure in a red t-shirt, whose facial expression is cautioning, as if warning us of something. The figure’s presence anchors the scene, drawing your eye to what is playing out on the canvas.

There are many ways to interpret “Pride of the Vanquished.” While it reflects the enduring strength of the human spirit, it also offers a compelling redefinition of what it means to be truly noble. This poignant exploration of resilience and inner strength amidst the aftermath of defeat and the winds of victory shows that in battle, dreams can turn to sand, eyes and spirits cast downward. Yet, a fire persists, for within defeat, a silent pride exists, and Leyland seizes it.

Throughout his works, Leyland seeks to apprehend the viewer’s attention like a moment of intense silence just before disaster strikes, or a breath held in anticipation—in other words, simply poetry in motion through painting.

Leyland has exhibited in various international exhibitions held in Australia, India, South Korea, and the UK. Furthermore, his exceptional talent has been recognised through his receipt of the Elizabeth Greenshields Grant not once but twice.

In an age dominated by art installations, digital media, video, and performance, what constitutes an artistic ‘practice’? This question gains new layers of complexity, perhaps more now than at any other point in the history of art.

Within this multifaceted context, Leyland’s dedication to the tradition of figures in landscapes finds its rationale. His adherence is not merely nostalgic; it underscores the enduring nature of painting. Despite the evolution of art forms, the timeless qualities of great painting persist and prevail. I caught up with the emerging artist to learn more about his practice, his sources of inspiration, and more.

Hi Danny, thank you for speaking with us. Could you introduce yourself to those who might not be familiar with your work?

Danny Leyland: I have made all kinds of different work, from performance and costume to video and artist-book work, much of it centred around my relationship to landscape, memory, narratives of the ancient past, and so on. In recent years, since about 2019, I have focused increasingly on painting, and, in a general sense, I might say I have been working in the tradition of figures in landscapes. It’s a tradition that spans from the early depictions of saints in the wilderness, through to the romantics, then Gauguin, Van Gogh, the Francis Bacon responses to Van Gogh, Munch, and, more recently, Peter Doig and Andrew Cranston.

Image courtesy of the artist

Can you share some early moments from your journey into the arts and explain what inspired you to pursue the path of an artist?

Danny Leyland: I never knew that you could study art at university! I don’t think I’d ever heard of art school. I had originally applied to study geography of all things! And then, one day, my art teacher turned around and said to me ‘have you thought about going to art school?’ and I was like, what’s that? He suggested that I apply for an Art Foundation, to see if I liked it, and I never looked back.

I didn’t set out with something in particular that I wanted to say, just that I knew I loved making things. I was enthralled by the excitement of “thinking with your hands”, or, to put it another way, of creating meaning through the handling of materials. I also loved the freedom of being encouraged to learn about whatever I wanted. And the way in which tutors, expanding on a discussion you had, would lead you down all kinds of weird and wonderful rabbit holes through different references and suggestions.

Your practice involves integrating drawing, print-making, and writing with painting. Can we delve into how these mediums interact with the themes you explore?

Danny Leyland: As an artist, I’ve found I’ve had to be really flexible in responding to my situation. I’ve moved around a lot and, in the “wilderness years” where I didn’t have access to a permanent painting studio, I would continue to work in other ways, whether it was writing short stories on the train or using the print facilities at the college where I worked in the evenings after class.

Different aspects of my practice remain quite separate I think. I don’t write about my paintings or paint from my prints. But I do find that each process allows me to address my interests and interrogate my research in different ways. Painting can feel immensely direct at times, because of its ability to hold the gaze, but it always exists very much within a certain language and tradition.

I find that in my writing, I can be much more personal and allow the imagination to run unchecked, probably because I don’t critically hold it to account in the same way. With print-making, on the other hand, I have found myself extending the way in which I organise and deliver a project, involving collaboration with other artists and writers and considering different ways to interact with audiences outside of exhibitions.

Image courtesy of the artist

In your work, do you find that one medium influences another more significantly, or do they coalesce seamlessly?

Danny Leyland: I don’t generally make mixed media works, if that is what you are asking. I’m quite a purist in painting, and I don’t tend to mix anything with the paints I use. Other aspects of my practice help support my painting. Most of the drawings I make are kind of plans or compositional ideas for paintings, although I do enjoy sketching for the sake of it, in museums and while travelling especially. I collect objects and photographs, and maintain constant notebooks. Going over these is like curating my own mini-museum. A joyful and often surprising process.

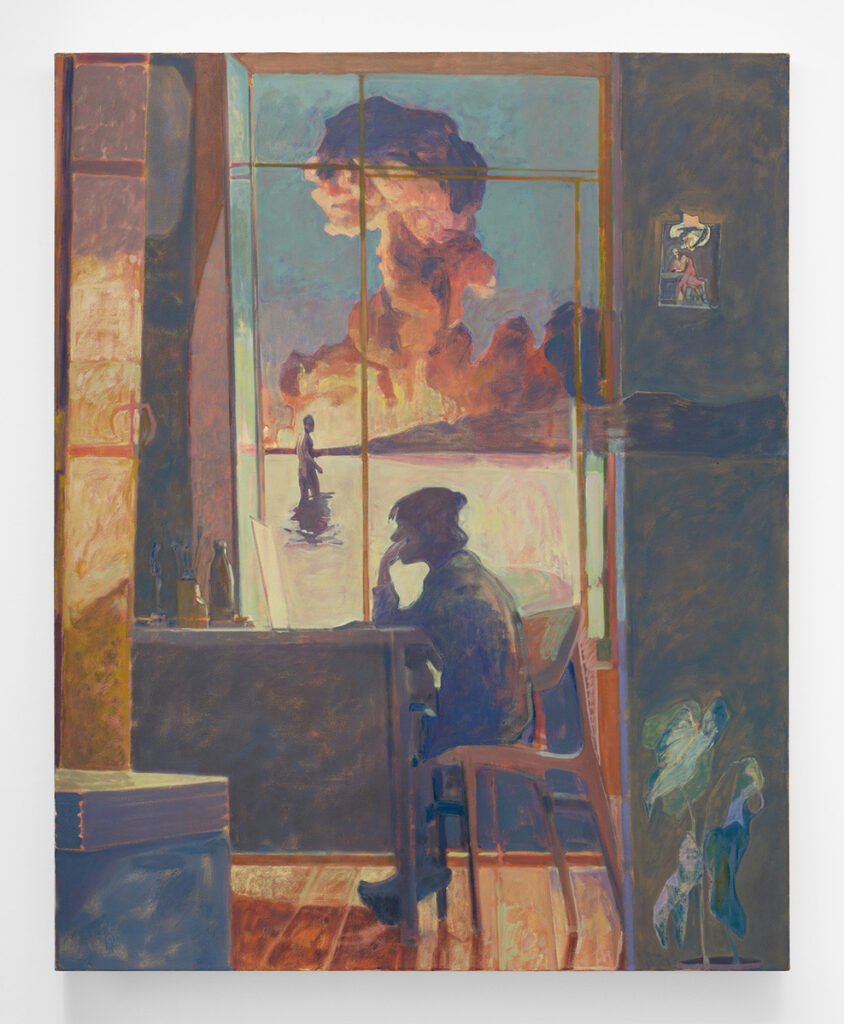

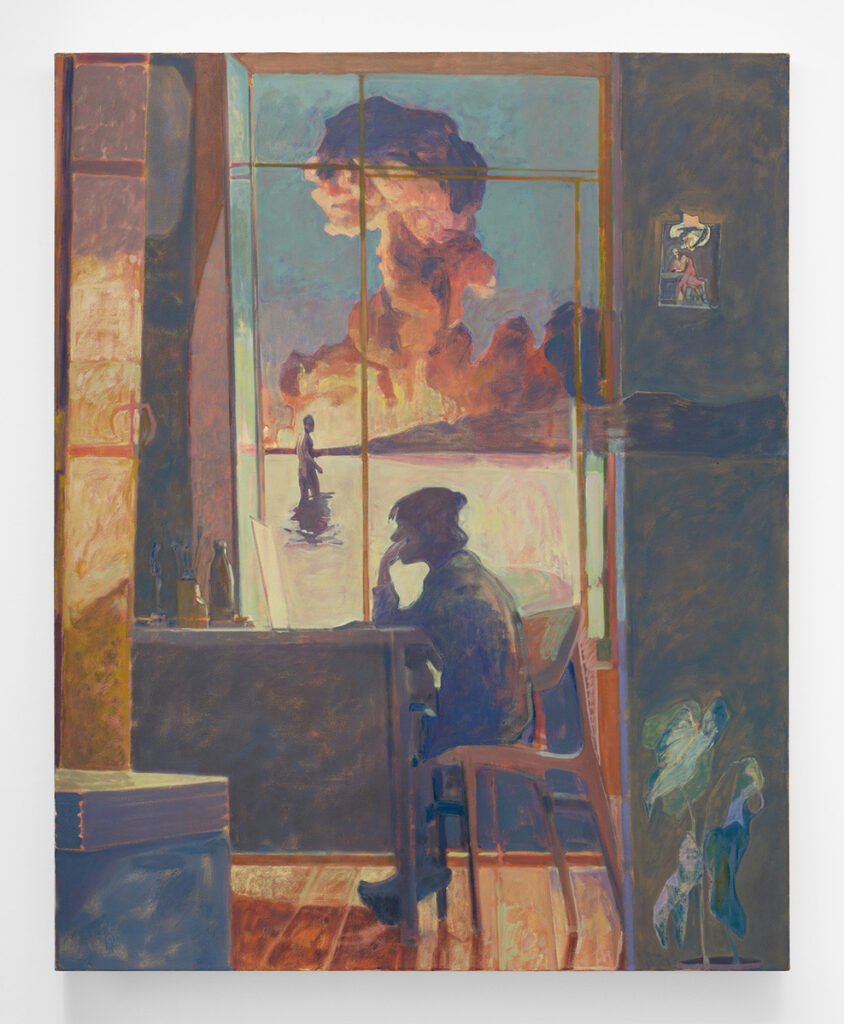

You’ve described moments in your paintings that “promise a sense of imminent eruption or contact”. How do you build this tension within your compositions?

Danny Leyland: I’m interested in finding the moment just before something is about to happen. That frozen second before the embrace, the silence before the mushroom cloud envelopes everything. – What Oli Hazzard called, in relation to Andrew Cranston’s paintings, ‘that sense of emotional vertigo’. Where this may be achieved in my own work, it is all to do with the contingency of selecting and using images, whether from my own collection of photos or from film-stills or reference books or whatever.

In some of the images, there is a transfixed quality to the figures, poised in mid-action, where the immediate past and present of the figures’ actions remain unexplained, caught in a ‘frozen present tense’ – to use John Fowles’ phrase. Elsewhere, I’ve used images in which the figure’s gaze or position interacts directly with the audience. In either case there may be a kind of sympathetic exchange between the subjectivity of the viewer and the figure in the painting.

A great example of where this exchange takes place is Piero della Francesca’s The Baptism of Christ, in which the body, pale and beautifully outlined, steps out from the painting and towards the audience, and you really feel as if you are about to come into the proximity of this person. Above, frozen in suspension, the trickle of baptismal water from the upturned bowl is just about to come into contact with his head.

In front of such a painting we can approach the idea of something like an ecstatic union, an experience which also encapsulates the opposite experience, the destructive potential of rupture or parting. My paintings are not religious paintings, but I guess I want them to operate in a similar kind of way, where the figures are not kept at a distance but appear with all the immediacy and presence of a vision. If the paintings are about closeness and imminence, they are equally about estrangement and disconnection.

Image courtesy of the artist

How does the concept of time influence your choice of scenes or subjects?

Danny Leyland: At one point a few years ago I studied a short course in archaeology. I volunteered for Archaeology Scotland, and I participated in an excavation on an Iron Age hillfort in North Wales. And so you could definitely say that I’m fascinated by the study of the past! Around the time of the pandemic, I was making these “burial paintings”, scenes of prehistoric burials reimagined in a contemporary environment. I was coming from this place where I was thinking about my relationship with the dead and buried in the landscape to re-conceptualise a sense of belonging to a place.

Part of my own experience of living in Briain’s wonderful layered and complex historical landscape, is this powerful sense of presence and closeness which at times I’ve found to be powerfully moving, the past suddenly making itself felt even in the most mundane and everyday moments.

See also

In my recent work, I have been using images from different sources, combined as part of the painting process into a single composition, bringing together their own light conditions, direction of shadow, their sense of movement and proportion, and also different kinds of clothing or objects from different time periods. As they converge, these shifting temporalities can help to create these slippages, these moments of eruption, where the past coexists with the present.

What reactions or interpretations from viewers have surprised or challenged you, and how important is the viewer’s role in completing the narrative of your works?

Danny Leyland: T.S.Eliot said that good poetry communicates before it is understood. A good painting is probably the same, in that, even if you don’t understand what’s going on, it should still engage an audience through its form, images, colour work, and so on.

I don’t want to give too much or make things too easy for an audience. I’m interested in creating the kind of painted surface which offers a “slow release” of information, requiring a sustained interaction from the viewer. To this end, I tend towards obfuscating and burying forms within the painting to merge together different spaces and perspectives, to fudge boundaries, and mute tonal contrasts. On the other hand, the coherence of the painting as a whole, its central images and so on, need to be allowed the space to cut through the painting and speak directly to the viewer. This is something I’ve been trying to work on across this year at the RCA. – To gain the confidence to realise the potential of the visual material I’m working with.

Image courtesy of the artist

In ‘You’re the Last’ series, you challenge the nature of reality with hunting scenes interlaced with tactile imagery. What inspired this theme, and what are you hoping to communicate or question about reality through these depictions?

Danny Leyland: Both of these paintings draw imagery from a colonial-era photograph I saw whilst travelling in Tasmania last year. My paintings often expand from an initial drawing or photograph, or film still, a thing chosen for the particular way in which it seems to recall an experience. I subsequently build a “world” into and around the image, adding elements of visual information, being led by the way in which these elements may disrupt or contribute to the composition or narrative, or both.

This photograph of the swan hunters was just such a case. I knew instantly when I saw it that it would make vivid and intriguing material for a painting. The beauty of the black swans, and the heroic poses struck by the hunters against the backdrop of the water, forms a striking contrast with the bleak history of ecological destruction and colonial violence committed against the aboriginal people. The images and stories of the past remain so alluring and beguiling, even when we are trying to educate ourselves as to the damage caused by the colonial project. I’m interested in the place where these conflicting emotions occur.

Image courtesy of the artist

Hunting scenes often carry rich symbolic meanings. In this series, what metaphorical dimensions are you exploring, and how do the disruptions you introduce play into these themes?

Danny Leyland: Hunting involves an element of ritual, strongly expressed through the costume and garb of the huntsman. In ritual displays, costume allows the participant to remove themselves from normal societal constraints, and so enter into a realm of transformed possibility.

In much of the imagery I use there is a quality of costume and performance, in images of horse-racing for instance, or rugby players, or woodcutters. I’m interested in the possibility that what we are seeing may only be a re-enacted or replica version of events, rather than the real thing.

In mediaeval romance literature, the hunt provides magnificent displays of courtly masculinity, where the knights all get the chance to show off their chivalric virtue and martial prowess. In the Gawain poem, for example, there is a section where the poor hero is dreadfully ashamed because he spends all day in bed being teased by the host’s wife, while his host goes off hunting every day. We are supposed to understand that Gawain is being emasculated twice-over, both because he isn’t galloping around the woods proving what a good sport he is, but also because his manly virtue is being tarnished.

In the mediaeval hunt, masculinity asserts itself through violence and establishes an exploitative relationship with the natural world. It’s broadly understood that the victorians were obsessed with mediaeval ideas of chivalry. They even re-enacted their own jousts and pageants! The men who went on to become army officers and government administrators in the colonial period, were brought up on the same chivalric lessons of violence and exploitation.

You’re the Last, my painting for the RCA show, is presenting these two forms of exploitative activity alongside one another. The model ship in the foreground is a Liquid Natural Gas carrier (it has LNG emblazoned on the hull), a key part of the global system of reliance on fossil fuels. And above the ship there is a band of working settlers from the 19th century, in what was then Van Diemen’s Land, hunting black swans.

The courtly hunting described in the mediaeval romances might have looked like Uccello’s 15th century masterpiece The Hunt in the Forest, but the swan hunters in their shabby coats share more of a resemblance to Pieter Bruegel’s famous hunters, slouching with bent backs through the snow. These are men with hats, toting guns. “Boys with toys”. I’m aware that I am a male-identifying artist, and that my paintings have this interest in masculinity.

Culturally we have been in a transitional period, through which many of the traditional myths of masculinity (including those involving hunting and fighting) have been found lacking and unfit for contemporary society, and, for some men, this has produced a crisis of identity. The title for my painting You’re the last, which comes from a line in the novel ‘Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy’ by John le Carré, refers to this crisis. ‘Poor loves. Trained to Empire, trained to rule the waves… You’re the last George’.

Looking to the future, are there any themes or techniques you haven’t explored yet but are interested in incorporating into future works? How do you see your art evolving in the next few years?

Danny Leyland: Yes, I’m working towards some exciting projects over the next year, including my first solo show in London. And really I would like to focus on creating a full response to the challenge, in a way that goes beyond a body of paintings. In collaboration with technicians and designers, I would like to develop the possibilities of my paintings-as-objects, in ways that might situate the work and the gallery within a domestic and more personal imaginative space.

Image courtesy of the artist

Lastly, could you share the philosophy that guides your art? How do you understand the core importance of art in your life and career?

Danny Leyland: I think I’ve always had the sense that being an artist is less important or less interesting to me than making art. – In other words, I do not think that artists are necessarily different from other people, or have been singled out as “one of the select”. I’m much more drawn to the idea of the mediaeval artist who is a bit of a journeyman, a travelling artisan. Someone who just puts the hours in, and gets on with the job! In terms of the work itself – well, there was an adage I learned whilst training to be a teacher, and that was that teaching is always professional, personal, and political – and I think the same is very true for art! None of us make work in a vacuum.

@danny_leyland

©2024 Danny Leyland

Len is a curator and a contributing writer at Art Plugged, a platform for contemporary art; he also engages in web development, design, and marketing.