When David Shelley, the CEO of Hachette, one of the “big five” publishing companies, was a teenager, he was living in Margaret Thatcher’s Britain and under a law called Section 28. The measure, which was in effect from 1988 to 2003, prohibited schools from “promoting the teaching of the acceptability of homosexuality.”

In the ’80s, Shelley said, his main sources of information came from teachers and libraries, and he described himself as being depressed because he didn’t see anyone like him. Then one day at the library, he stumbled across Aidan Chambers’ 1982 novel “Dance on My Grave,” about two teenage boys in love.

“That was a lightbulb moment for me, because finding that book in the library that somehow had escaped Thatcher’s law — it was actually a real lifeline,” Shelley said.

Shelley was named CEO of both Hachette’s U.S. and U.K. divisions last year, and the new job came with a move from London to New York City. Living in the U.S., he said, has brought back the complicated memories of his youth.

“It felt like I was back in Thatcher’s Britain in the 1980s. Not in all states, but in some states,” he said.

Shelley said he fears the yearslong spike in book censorship efforts in the U.S. will lead young people to face similar feelings of loneliness and isolation he experienced as a teen.

In observance of Banned Books Week, which started Sunday and runs through Saturday, two new reports were released. The first, from PEN America, documented a sharp increase in books removed from school shelves in 2023-24, tripling from the previous school year. More than 8,000 books were pulled in Florida and Iowa, two states with laws that restrict LGBTQ-themed books in schools and libraries. The second report, from the American Library Association, found complaints have dropped this year but still exceed numbers prior to 2020. The PEN and ALA reports don’t necessarily contradict each other, as the two organizations define book bans differently.

“I can understand some of the impetus where people are thinking they’re safeguarding kids or they’re protecting kids. But at the same time it’s very dangerous, because one person’s idea of what safeguarding means is actually depriving kids of valuable sets of information,” Shelley said, pointing out a sizable portion of banned and restricted books are written by people of color and LGBTQ authors. “So actually in the supposed safeguarding of kids, what you’re actually doing is depriving them of representation.”

What the reports do not quantify is the collateral damage of book bans, or so-called soft censorship, when a title is excluded, removed or limited before it is explicitly banned, out of fear of backlash. This could look like the removal of books due to complaints from parents or a librarian declining to carry a title out of concern about an impending ban or challenge. According to the ALA, surveys indicate 82%-97% of book challenges go unreported and receive no media coverage.

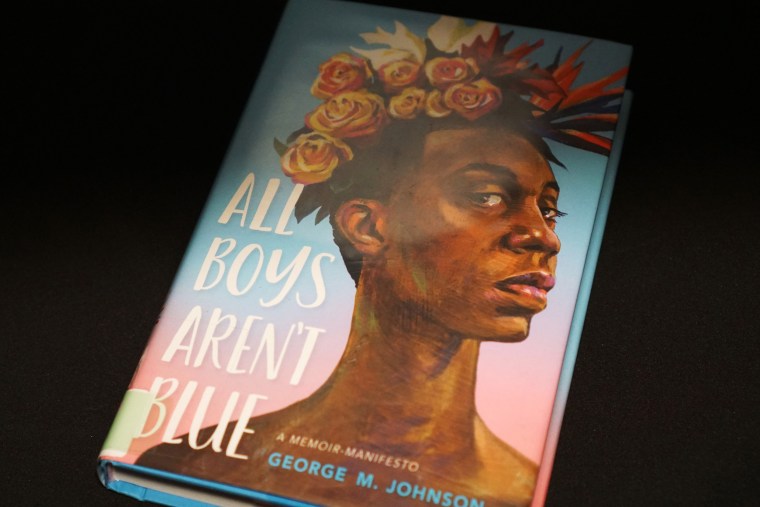

“I do think when we talk about soft-banning, where it applies heavily is schools and libraries. Where they won’t even order the books for their library,” said George M. Johnson, whose first book, “All Boys Aren’t Blue,” is one of the most banned books in the U.S. “So I think that is where the danger lies, because we can track the books that are being banned, but we can’t track books that are not being ordered.”

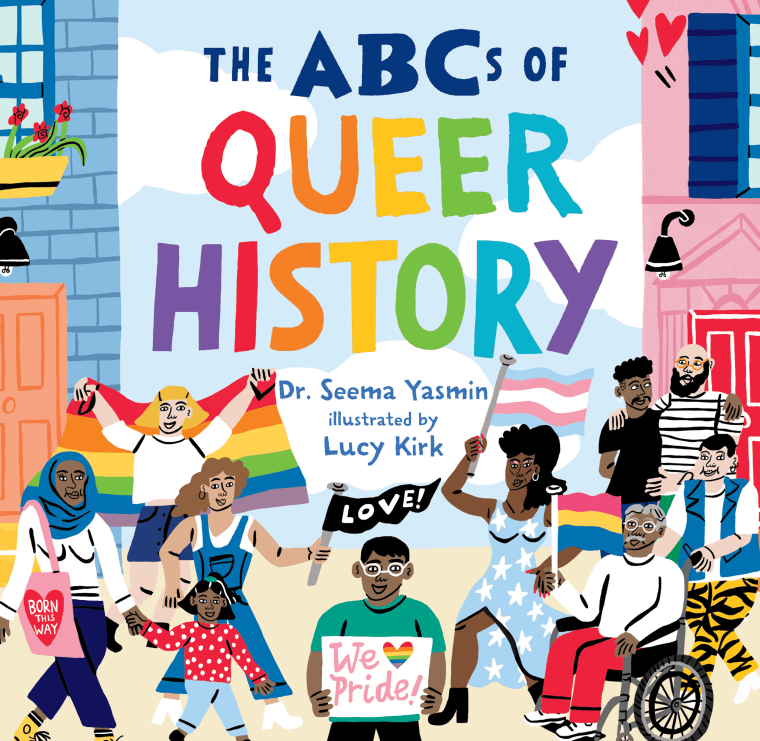

Dr. Seema Yasmin, an author and physician, said her debut book — “The ABCs of Queer History,” a children’s book published in April by the Hachette imprint Workman Publishing Co. — was soft-banned earlier this year. She said a big-box retailer, which she declined to name, canceled a large order of the book before it was even published, saying it was pulling back on Pride celebrations.

“What I expected was more of, ‘A parent in Dallas County has said they don’t want the book taught in their school.’ I did not expect a huge corporation to order and then rescind a 10,000-copy order, which is a whole print run. I didn’t see that happening.”

Yasmin joined the American Civil Liberties Union last week in Georgia for its “Know Your Rights Bus Tour.” She brought “The ABCs of Queer History” and her new book, “Unbecoming,” a young-adult novel published by Simon & Schuster about two Muslim teens in Texas fighting for abortion access. Yasmin said she began writing the book in 2019 after thinking about how abortion bans affect teenagers.

While teachers and librarians have praised her latest book, Yasmin said, some have told her they are not going to teach it or keep it in the classroom because they fear it’s going to get banned. “So what we’re seeing is this censorship happening before the book is banned because of the draconian ecosystem that we’re living in,” she said.

Teachers and librarians may face a variety of punishments if they are found providing a book that is challenged or banned, or, in some cases, if they share a book that is likely to be challenged. Depending on the state, it can be unclear how to comply.

In Florida last year, two school districts told teachers to conceal or remove every book while texts went under review for compatibility with a new state law. And in Utah, a recently introduced bill proposes teachers be charged with a misdemeanor if they keep materials available to students that have been classified as “objectively sensitive.”

In August of last year, an elementary school teacher in Georgia was dismissed for reading “My Shadow is Purple” to students, a bestselling children’s book about acceptance and the gender binary. The teacher, Katie Rinderle, was found to be in violation of a 2022 state law prohibiting the teaching of “divisive concepts.” Attorneys representing Rinderle said the definition of “controversial issues” is so vague that teachers can’t be sure what is actually banned, according to The Associated Press.

And in June, NBC News published an investigation into an officer in Texas who spent two years vigorously pursuing felony charges against local librarians for allowing children to access literature he deemed obscene (such as “The Bluest Eye” by Toni Morrison). The county’s district attorney ultimately turned down the officer’s request to indict the librarians, citing a lack of conclusive evidence.

This week, Johnson, who uses they/them pronouns, released their latest book, “Flamboyants,” a collection of essays about Black and queer icons from the Harlem Renaissance. Its release during Banned Books Week was a coincidence, though Johnson acknowledges the book will likely be banned at some point.

Johnson is a plaintiff in PEN America et al. v. Escambia County School District, a federal lawsuit alleging school administrators in the Florida county are in violation of the First and 14th Amendments because the district’s book bans violate a right to free speech and equal protection under the law.

Johnson said they joined the lawsuit to show “how serious I’m taking this and how serious I am about the protection of young people and their ability to learn about their identity.” Johnson said it was also their experience having their work banned that inspired them to take action. “I was like, OK, if they want to go this far, I have to take it a step further myself.”

Next year, Johnson will release a book co-written with author Leah Johnson (no relation), whose books center queer girls of color. One of her young adult novels, “You Should See Me in a Crown,” was placed under review by the Oklahoma attorney general in 2022 to determine if the book violated the state’s obscenity law.

Leah Johnson founded a “banned bookstore” called Loudmouth Books in Indianapolis last year. She said she was inspired to launch her bookstore after a library in Indiana moved more than 1,300 YA books into its adult section under a controversial new review policy that reshelved famous teen books like “The Fault in Our Stars” by John Green and Judy Blume’s “Forever.” While the library suspended its review policy after significant backlash, it was enough to convince her to take action.

“I know how important the role of the independent bookstore is not just in publishing, but also in local communities. It felt like a natural continuation of the work I was already doing,” Johnson said of starting her bookshop. “I think it’s worth remembering that they’re not trying to remove books from shelves. They want a removal of queer people from public life.”

Loudmouth Books is particularly interested in highlighting both banned books and the work of marginalized authors, with an aim to challenge the idea that diverse stories are inherently dangerous. (“But if they are, sign us up to read dangerously!” the bookstore’s website says.)

In the meantime, Leah Johnson’s book with George M. Johnson comes out next year, the first in the duo’s seven-figure, two-book deal featuring Black, queer characters.

“It’s just fun to write gay s— with your homie,” she said. “That’s what I want to do. That’s what I’m thinking about.”