Twenty-six years ago, the Iowa metal band Slipknot arrived at the Malibu studio compound Indigo Ranch to make one of the gnarliest albums of the 1990s in one of the most beautiful places on Earth.

“I remember going down the PCH, the Pacific Ocean sparkling, headed up Barrymore Drive into Solstice Canyon with our 2-ton truck of gear and thinking, ‘We’re so out of our element,’” said percussionist and founding member Clown (Shawn Crahan). “I remember it being polar opposites, being in an insanely beautiful place, making this festering thing.”

The self-titled debut that emerged in 1999 raised the bar for scabrous yet song-driven riffing, at a time when nü-metal fought teen pop atop the charts and on MTV’s “Total Request Live.”

Making an immediate statement with its nine-piece lineup and grotesque masks hiding members’ identities, the band would go on to earn three No. 1 albums. Rather than compromise its sound for rock hits, though, the band became a full-on subculture. The drum throne of Slipknot is a hotly debated seat in heavy music; a slot on Knotfest announces your prowess to the scene.

Two years after its seventh LP, “The End, So Far,” the band is celebrating the anniversary of its self-titled debut album, whose corrosive imagery and experimentation still inform metal today. The tour hits Intuit Dome Sept. 13-14 (the first hard rock shows in the shiny new arena).

The Times spoke with Clown and the band’s ferocious new addition, 33-year-old former Sepultura drummer Eloy Casagrande, about the impact of that first album, the curse of phones at shows and Clown’s off-duty life in Palm Springs, of all places.

I wish I could have been there for Eloy’s debut at Pappy & Harriet’s in April. That’s not a venue you’d expect to see Slipknot in.

Clown: We came up the ladder in clubs that would allow us to be very interesting. Now that we’re celebrating this 25th anniversary, which is half my life, I wanted to prove to myself that we could still do that. I wanted to pick a location that didn’t sound obvious but still had good viewing. We put up a billboard and one of the maggots [Slipknot’s fans] took a picture and sent it out into the culture. The feeling was beyond expectations from the minute we stepped onto the grounds.

Eloy Casagrande: When I first got the call from management, I went crazy. I had to keep silent, just my wife and mom were the only ones who knew. I’ve listened to Slipknot since I was a kid in South America — I never imagined they’d choose a drummer from there.

I had four months to prepare for that show, and the homework was so intense. The whole day, I was in shock. My wife came and we spent a few hours in the city there, and 20 minutes before we went on, I felt really calm. The band came and gave me a hug, and the show was one of the best of my life.

This tour is revisiting the 1999 self-titled album. Those sessions were famously intense. Is anything lost now that many bands would make that album at home on a laptop?

Clown: Most people won’t make a record like that now. It costs too much. We spent so many weeks in preproduction, then doing 10-hour days cutting the whole album to 2-inch inch tape, just insanity. We were very blessed to work with producer Ross Robinson, but he was intense. It’s good to be pressured, it’s good to have someone point at you and to be scared because you’ve got to think differently.

Real music, from Roy Orbison to Phil Spector to Aretha Franklin and Muddy Waters, there’s a lineage of exploring sound put onto tape, how vibrations turn into electricity. We’ve gone from John Lennon to just putting a record out on YouTube. How much of that will be here in a year? Ten? My band is still relevant 25 years later and we’re at the top of our game because we came up within that lineage. When music’s no longer the truest vibration of itself, I can hear it.

Metal was doing well on the pop charts at that time. Did it feel like you were making a notably challenging record?

Clown: As a band, you have landscapes in your head. I had a dark forest, graves, a deep molten smell, and we found our own ways to unlock that. You hear it and think it’s gonna change the world. I remember people looking at the CD cover, seeing the band and going, “What the hell am I listening to? Who the hell is this on the cover? A circus? Bank robbers?“ Then they’d see us, put our faces with the instruments, then it’s over for everyone.

Eloy, what struck you about that album when you heard it as a kid?

Casagrande: It’s the energy, the way it’s recorded pretty much live. I did an album with Ross Robinson in Sepultura, I know the way he works. They were fighting for their life, for their art. The whole history behind it is very heavy, and the first time I listened, I was in shock, it was so different than everything — just raw, aggressive, natural and human.

People have an idea that metal sounds like a machine, but Slipknot’s the opposite, it’s all so human. I’m never trying to be a machine, I want to respect the moment we’re in. We don’t play with a metronome, I only have one onstage so I can look at it and count in at the right tempo. Ninety percent of bands use backing tracks and metronomes, but we play 100% live.

How do you mesh the band’s style with your own Brazilian music background?

Casagrande: I was a little afraid, but the band wanted me to bring new ideas, new elements. I remember Shawn said to me, you can put your personality in there, you can be yourself.

I really respect what Joey [Jordison, Slipknot’s original drummer] and [former drummer] Jay [Weinberg] did for the band, they were both so special and they are legends. But I grew up playing Brazilian music, that’s in my blood. When I play metal, Brazilian stuff is inside of it. It’s only been six months, but Slipknot’s changed the way I play my instrument too. We designed my mask together that fits my personality, and when you put on that makeup and play a show, it changes you.

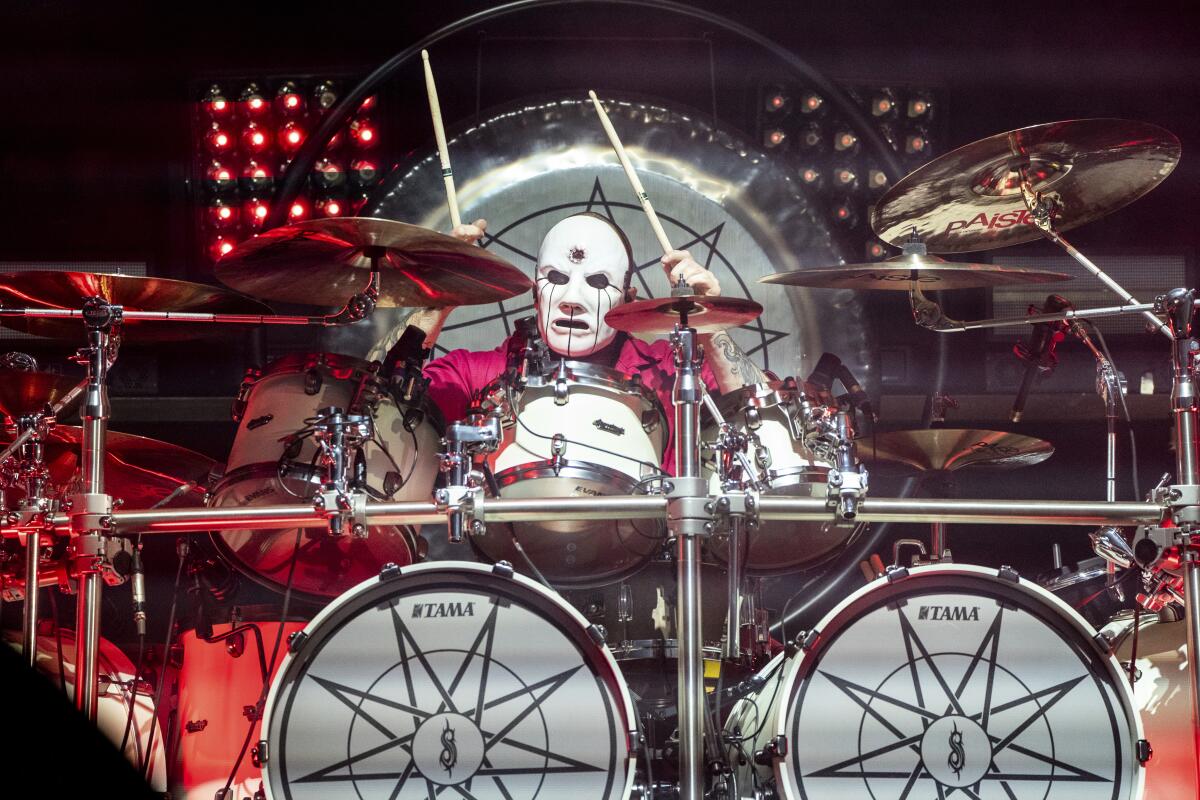

Eloy Casagrande of Slipknot performs during Sonic Temple Art and Music Festival in May at Historic Crew Stadium in Columbus, Ohio.

(Amy Harris / Invision / Associated Press)

What’s at the core of Slipknot’s aesthetic and community that still hits new generations 25 years later?

Clown: Every year you have young men and women in high school that want an aggressive song as the theme to the way they think. Young adults are looking for a cultural identity, dealing with their parents’ divorce, the pressure of isolation, chemicals. Like all good older brothers and cousins who hand out music they love, Slipknot does have a way of keeping your attention. What we created, they still get it. We have grandkids coming to shows, new babies brought to shows with Mom and Dad.

You might be an aggressive male when you’re younger, then you learn from great people and get more confident, but you never lose that past. Metal fans always come back to our philosophy, and I do believe metal is a behavioral thing. When you find something like Slipknot that speaks to you, you never give that up.

So little popular music uses live drummers to make records anymore. Slipknot is first and foremost built on drumming. Eloy, where is interesting drumming flourishing right now?

Casagrande: Rock and metal bands, we have an old-fashioned mentality. Look at pop, it’s totally different, you just hire random musicians to play with you. You can find creative drummers everywhere, and there’s a lot of good music being made, but for the creative stuff in jazz, fusion and metal, you have to find the people who want to make it. In metal, we all know each other, and for the fans who follow metal, they know the band members, they care who the drummers are.

It’s been a challenging few years for the band, beyond big lineup changes and [singer] Corey Taylor’s struggles with manic depression. Former drummer Joey Jordison passed in 2021. Clown, you lost your daughter in 2019. Slipknot helps people make sense of bleak emotions — do you get the same thing out of the band?

Clown: The last few years, there have been a lot of things with Slipknot. It takes time and communication. We’ve been through stuff, but we’re still doing it. I’ve been through a lot. I lost a child. It’s important to acknowledge when you’re not happy, and man up and be a good human for the right reasons.

It’s hard to talk about the 25th anniversary without Joey and Paul [Gray, bassist who died in 2010]. They would have so much to say, and I’d love to hear what they have to say. Now I have to talk and it makes me feel weird. But I do get something out of it. The only way I get up onstage is because I dance with my god, music. I’m in awe of the musicians I keep company with. If I didn’t have 90 minutes onstage, there would be no me.

I came from an extremely alcoholic father, but he’s my best friend, and rock ’n’ roll helped me with that. It brought me together with him and with people who suffer. I don’t know if we’re considered a great big rock band, but we will always be considered a culture.

Have the live audiences for metal changed in the film-everything-on-your-phone era?

Clown: You have the OGs who teach people what’s up. If you’re on your phone, just going from one thing to another, it’s hard to get a vibe. It’s different now, but hard music is always gonna be there, it’s very consistent to human behavior that we need to fulfill our aggressive side even if the tech has changed.

Casagrande: You come to a show and have fun, bang heads and go crazy. But some people are more concerned about recording a video you’re never gonna watch again instead of being in that moment, which is something we always fight for in metal.

Slipknot arrives on the 2024 Grammys red carpet at Crypto.com Arena in Los Angeles.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

People are worried about young men drifting into antisocial subcultures. To me, a band like Slipknot is crucial to channel those feelings into something creative and communal. What does your band understand about the disaffected?

Clown: I learned by talking to people like soldiers and cops. I talk to a lot of police and military guys about the music that keeps them going. It’s a needed thing. Men need to blow off steam. I had real problems growing up, but thank God I found music and an instrument. The minute I started playing drums, it was a physical thing to take it all out. I broke knuckles, broke cymbals. Then you learn technique, which starts with breathing, and now you can harness it. Drums helped me harness and wear off my bad side. I went through a lot, but music grounded me.

Eloy, you spent almost half your life in Sepultura. Do you see yourself in Slipknot until the end?

Casagrande: I would love to spend years to the end of the band with them. The decision to leave Sepultura was because the band was ending, but I was too young to stop playing. I respect them, I have a lot of gratitude for my 13 years with them, but I had to move on. I want a band that’ll keep me alive, a living band open to everything that will keep moving forward.

Last thing: Clown, I hear you’ve moved to Palm Springs, which is not exactly a Slipknot kind of town. How’d you end up there?

Clown: My wife and I wanted to get out of Des Moines three years ago, and we wanted to live somewhere hot. We went to Palm Springs to see if it had the magic, and it was a religious experience with the heat, it gets in your bone marrow. After a couple of weeks, we were lying out by the pool, and she said, ”I could live here.” We’ve had unfortunate things happen and we wanted to get away to a special place, and this was just the best thing for us — no clouds, just sunny days.

Do your more straitlaced neighbors know you’re Clown from Slipknot?

Clown: Nobody knows yet, and the very few that do don’t understand until they’ve witnessed it in person. Some people from our day-to-day here came to Pappy’s, and once you see Slipknot, you’re a fan. But we lay low here — I’ve got a pool, I can decompress, I chill, I love it.