I met him when I took his beautiful daughter Dorthy Williams on a date. It changed my life I wanted to be like him. He came into the room and he just had this presence about him and I wanted that for my life. He was a Dr of Psychology. I got to tell him at a conference how he changed my life and it made my year. He had to know what he had done for me. He was a rock star in my world. He was so kind and wonderful. He was for his people and he did not shy away from them trying to paint us as less intelligent. Ebonic was his term and we use it today. Peace be with you my God bless your whole family.

Robert Lee Williams II is a leading figure in American psychology known for his work in the education of African-American children and in studying the cultural biases present in standard testing measures, especially IQ tests. He was inducted into the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame in 2011.

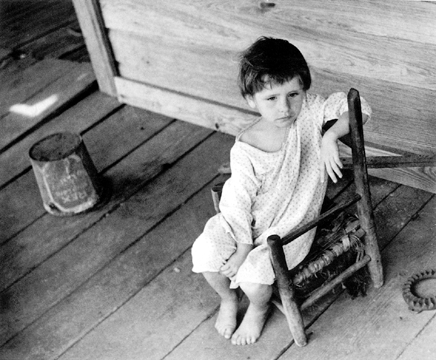

Robert Lee Williams was born on February 20, 1930, in Little Rock (Pulaski County). His father, Robert L. Williams, worked as a millwright and died in 1935; his mother cleaned houses. He had one sister. He graduated from Dunbar High School at age sixteen and attended Dunbar Junior College for a year before dropping out, discouraged by his low score on an IQ test. He married Ava L. Kemp in 1948. They have eight children.

After working a few different jobs, including in construction and in a carhop, Williams enrolled at Philander Smith College, graduating cum laude in 1953. From there, he went on to Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan, where he earned a master’s degree in educational psychology in 1955.

For several months, he was employed as the director of guidance at the high school in Mound Bayou, Mississippi. In 1955, he was hired by the Arkansas State Hospital as a staff psychologist. Encouraged by his supervisor to pursue a doctorate, he went on to study clinical psychology at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, where he earned his Ph.D. in 1961. He subsequently served as the assistant chief psychologist for the Veterans Administration Hospital in St. Louis (1961–1966); director of a hospital improvement project in Spokane, Washington; and consultant for the National Institute of Mental Health in San Francisco, California, starting in 1968. Following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in April 1968, Williams helped to organize the Association of Black Psychologists, founded in San Francisco on September 2, 1968. He served as president of the association from 1969 to 1970.

Following the assassination of King, Williams experienced a growing consciousness of the black experience and his own blackness. After briefly serving as the chief of psychology at the Jefferson Barracks Veterans Hospital in St. Louis, Williams took a position with his alma mater, Washington University. From 1970 to 1992, he was a professor of psychology there, where he also developed the African and African-American Studies program, serving as its first director.

In a paper presented to the American Psychological Association in 1972, Williams described the results of a 100-question intelligence test he had created, the Black Intelligence Test of Cultural Homogeneity, or the BITCH-100. Questions employed a cultural context more familiar to African Americans, and, consequently, white takers of the test scored lower than their black counterparts. This work has become part of a larger body of evidence showing how standardized IQ tests exhibit racial and cultural biases that result in lower scores for black students.

However, Williams’s most well-known work is his study of black linguistic practices. In 1973, he coined the term “Ebonics” to encompass the vernacular English often spoken by African Americans, claiming that some of the features of so-called Black English can be traced back to various African languages (though this claim is controversial among linguists). Two years later, he published the edited volume Ebonics: The True Language of Black Folks. His work on Ebonics remained relatively obscure in mainstream circles until 1996 when the Oakland School Board in California resolved to recognize Ebonics as a language employed by its students. This was done to access funding for bilingual education. The subsequent uproar from politicians and linguists resulted in Williams making numerous appearances on national television to explain Ebonics.

In 1980, while serving as a visiting professor at the University of Texas in Austin, Williams wrote his second book, The Collective Black Mind: Toward an Afrocentric Theory of Black Personality, which argued for the employment of African philosophical concepts and terms for the study of African Americans, rather than those derived from a European philosophical tradition. Williams also published “Racism Learned at an Early Age through Racial Scripting” (2007) and a 2008 history of the Association of Black Psychologists, in addition to more than sixty scholarly papers.

After retirement, Williams served as a visiting professor at the University of Missouri in Columbia from 2001 to 2004, holding the position of the interim director of Black Studies there from 2002 to 2003.