“It is always instructive to read European newspapers on American affairs. It gives us the much needed opportunity to see ourselves as others see us – with their eyes shut. . . Do we not all reek with malodorous lucre? Are we not a nation of tradesmen?”?

Thus W. J. Henderson, in the New York Sun (March 8, 1908), on the arrival of Gustav Mahler in New York to conduct at the Metropolitan Opera. Henderson – for half a century, a great name in music journalism — was commenting on exaggerated Viennese accounts of Mahler’s financial terms of engagement at the Met. He added:

“The coming of the new interpreter of German operas was awaited with interest and received with pleasure, but there was no public excitement. The stock market was not affected.”

Henderson was merely correct. New York critics knew far more about musical Vienna than Vienna – including Mahler himself – knew of musical New York. When Mahler reported “absolute incompetence” at the Met, he did not realize that Heinrich Conried, the impresario who hired him, was a clownish successor to the Met regimes of Anton Seidl and Maurice Grau, during which New York boasted ensembles of German and Italian vocal artists that no European house could match. And when Mahler called his New York Philharmonic “a real American orchestra – talented and phlegmatic,” he had no idea what he was talking about. The premiere American orchestra was the Boston Symphony, whose conductors had already included Arthur Nikisch. Mahler’s Philharmonic was a shaky aggregation, a pathetic sequel to the concert orchestra Seidl had led.

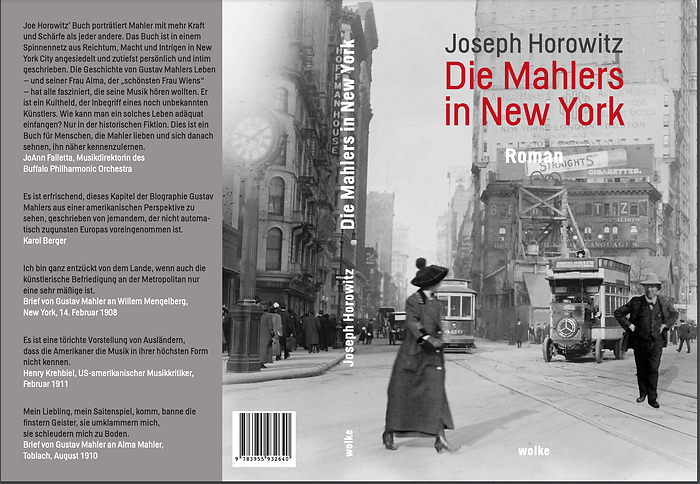

My novel The Marriage: The Mahlers in New York (also published in German as Die Mahlers in New York) attempts to set the record straight. The most recent (full-page) German review, in the Frankfurter Rundschau, calls it “an important addition to the European Mahler literature. In contrast to Mahler, Joseph Horowitz paints an extremely positive picture of the American musical scene.”

In fact, I would not be at all surprised if my revisionist take on Mahler in America more impacts abroad, where cultural history doubtless retains some degree of vigor. In the US, the institutional history of classical music in America has never excited much interest among scholars. Even our orchestras and opera companies – including the Met, the New York Philharmonic, and the Boston Symphony – show little awareness of their own past achievements.

I am reminded that the current Sesquicentenary of Charles Ives is, at this moment, more celebrated in Europe than in the US. Fifty years ago, when Ives turned 100, Leonard Bernstein and Michael Tilson Thomas were prominent celebrants, and a major Ives Centenary conference was mounted by H. Wiley Hitchcock and Vivian Perlis. Nothing like that is transpiring in 2024 – excepting four Ives festivals initiated via the NEH Music Unwound consortium which I am fortunate to direct.

My next NPR “More than Music” feature, scheduled for August 22, will exlore the musical odyssey (rather than the marital travails) of Leonard Bernstein. Even Bernstein is little remembered; young American musicians don’t know his name. And Bernstein himself was increasingly alienated by what had become of the America in which he had once placed enthralled hopes. The baritone Thomas Hampson, who sang with Bernstein as much as anyone did, comments on my upcoming broadcast:

“I think we [in the US] are in this phase, we are in this time, when things of worth and value that we treasure are easily forgotten, and not learned from. There seems to be this maniacal preoccupation with forward and future, and in the business world steady growth and steady profit. And you kind of have to wonder where the common good sits, and where the collective good sits. And the arts – they’re about the pursuit of happiness in our beautiful Declaration of Independence, they’re about the contented life, about the realization of being human. I think we are in dangerous times for people seeking enrichment to live. That may sound glorious and grand — but I’m a student of Leonard Bernstein. I don’t think anyone should doubt for a second the weight on Lennie’s soul. And I think to understand Lennie’s reaction in the sixties to all of that would be terribly illuminating for people today.”