In Lucy Ives’s new novel, Life is Everywhere, she writes: “Everyone who has ever lived was born into something that was already taking place.”

Article continues after advertisement

As children in New York City in the 1970s, we were born into a world covered with paint. Walls, baseboards, moldings, even radiators might be six or seven layers deep with it, architectural edges and corner blurred into globs, approximate shapes. Sometimes you’d find paint over old black-and-white checkerboard tile on the floor of a bathroom, or covering leaky pipes beneath a sink. Old landlord strategy: Throw on another heavy coat. It might be holding the building together.

The layers peeled and chipped. We were warned not to eat it. That made us curious: Was it good to eat?

At the dawn of gentrification, some of the layers were being undone. Chipped at or stripped away. People dragged sinks or sections of marble fireplaces into the street and poured and scrubbed poisons, hoping to free their old forms. A summer afternoon went rank with solvent.

Soon enough, some of our number went out armed with paint and shouted back with our own application.

Blake Lethem, F.C. crew wall by KEO XMEN and WEST FC, c. 1984.

Blake Lethem, F.C. crew wall by KEO XMEN and WEST FC, c. 1984.

These efforts called forth more layers of paint, in a struggle to conceal the visual funk that had birthed overnight.

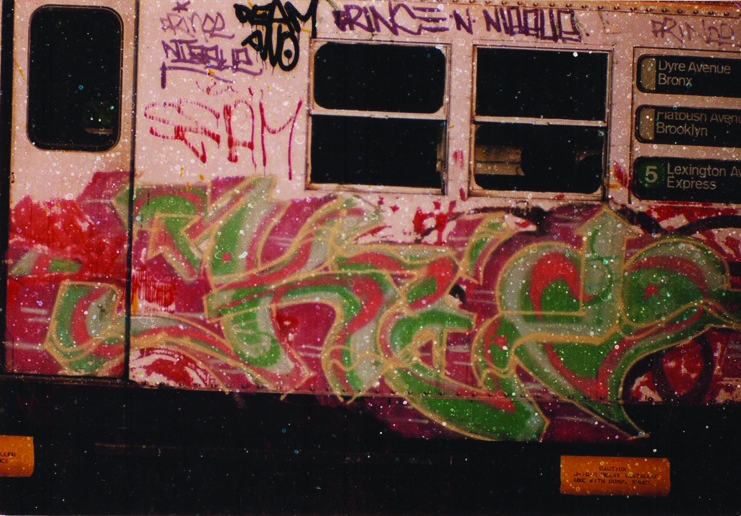

The ’80s explosion of graffiti caused the IRT to slather its rolling stock with graffiti-resistant paint, first fat white and later forest green and burgundy.

Not that a coat of graffiti-proof paint stopped my brother, although he was chased off before he could complete this panel.

Blake Lethem, KEO panel, Lexington line, c. 1985.

Blake Lethem, KEO panel, Lexington line, c. 1985.

In the ’90s, he got a go at this Redbird—but only because it was in the scrapyard, waiting to be sunk into the ocean to create an artificial reef.

Blake Lethem, Doomsday/Scrap Train.

Blake Lethem, Doomsday/Scrap Train.

Sometimes art is a game of survival. Live long enough, like my brother and some of his affiliates, and you might get celebrated, even paid, for that for which you’d earlier been prone to be arrested.

But graffiti artists from my brother’s era didn’t call themselves “painters.” They called themselves “writers.” Broadcasting your adopted name, however gnomic or illegible to those not schooled in the stylistics of graffiti font, was a language act. Writing graffiti was an action not only in visual space but a verbal blurt, a gesture aloud.

The flamboyance of the major panel work was grounded in the baseline activity of “tagging”: marker or spray paint calligraphy, word-as-icon, a signature on the city’s face.

When I left New York City for college in Vermont—where I would change myself from a painter to a writer—I stood one day with some friends beside a wall when one unveiled a spray can and undertook a little vandalism. (He drew a dick, as it happens.) Then he handed it to me, and, almost without thinking, I threw up a simulacrum of a tag I’d used in Brooklyn, on a warehouse wall or two, and once in a train tunnel, while accompanying friends who really wrote.

Graffti inserts itself like the blade of a knife between creation and destruction, between publicity and furtiveness, between word and image, cartoon, icon, and hieroglyph.

The response from my college friends was startling. They thought I’d hidden the fact that I was a graffiti kid. I explained otherwise, but they took it for modesty. I knew I wasn’t. I hadn’t done the time. The ethos of graffiti was that of endurance, repetition, diligence. You claimed the role in hours, in miles, in numbers of train cars or subway station pillars bombed. The X-Men, for instance, were celebrated as the last crew to have hit every line in the system. Far more than doggedness, this was the art itself.

There were days when I’d ride to high school on a train Zephyr had hit the night before and I’d count what seemed like a hundred fresh, dripping tags, as he’d roamed from car to car filling each available panel or door.

Like Sherwin Williams, it seemed one day Zephyr might Cover the City.

Andrew Witten, Zephyr tag.

Andrew Witten, Zephyr tag.

This value accounts for the eerie reverence held in the graffiti annals for PRAY, the old woman who managed to scratch her four-letter tag (or injunction) onto every single payphone in the five boroughs, as well as nearly ever pillar in every station in the system. Technically this wasn’t graffiti but “scratchiti,” yet the writers honored her with their awe. PRAY was an apparition, a rumor, an impossibility. She was also the Queen of the Boroughs, the greatest tagger who ever lived.

In the subways, the city’s unconscious, PRAY made it into movies, like Brother From Another Planet.

Roger Gastman, Pray scratchiti, Brooklyn, NY.

Roger Gastman, Pray scratchiti, Brooklyn, NY.

When Norman Mailer wrote his premature—but prescient—celebration of graffiti in 1974, he titled it “The Faith of Graffiti.”

This devotional, graphomaniac, filibustering dimension of graffiti haunts me. It suggests tagging as a version of call-and-response, within a city whose cacophony of advertising, decay, and squabbling vernacular voices begs reply.

Maybe it’s all a form of prayer—prayer to exist.

A flâneur, the walker-in-the-city, confronts the swaths of human reality that modern civilization has drawn into one place. But the classic image of the flâneur—from Baudelaire, by way of Poe—is of a silent, anonymous watcher, observing but unobserved, leaving no trace. The graffiti flâneur is equally driven to survey the city but also jabbers back at what they encounter, in the form of tagging. Their call is to anyone who’d care to notice. But, above all, to others of their type— those fellow graphomaniac walkers who comprise the rival crews.

I can’t outrun this image. Motherless Brooklyn’s Tourettic detective is a form of verbal graffiti artist. Perkus Tooth, in Chronic City, is another, wheat-pasting his cryptic manifestos on lampposts and garage doors. And in the last line of The Fortress of Solitude I dubbed the book’s characters—those fated to have to carve their personal selves from the city’s havoc of simultaneity—“human scribble.” I’m not entirely certain what it means. The phrase suggests a kind of animation or vibrancy, but also that they might be subject to being overwritten, overpainted—erased from the scene.

Graffti inserts itself like the blade of a knife between creation and destruction, between publicity and furtiveness, between word and image, cartoon, icon, and hieroglyph. Beyond its incorporation of actual characters—Doctor Doom, Underdog, Cheech Wizard—the words and letters themselves slide toward mummery or Kabuki, cloaking their sense in costumes, in masks. That its meaning is inchoate is part of the point. If you can explain it, you probably don’t understand.

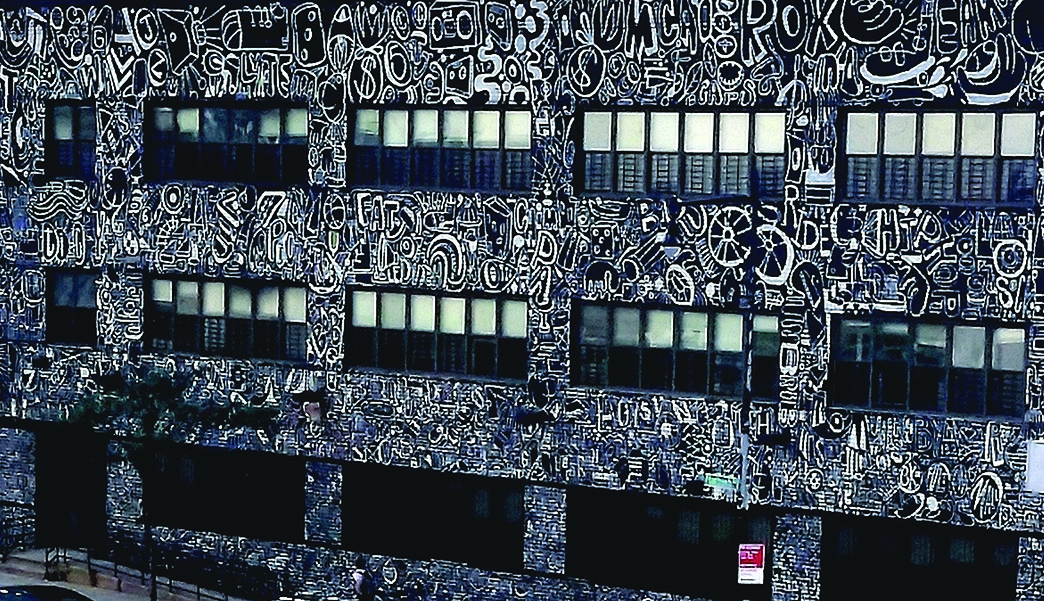

Katie Merz, Flatbush Mural (detail), 2017.

Katie Merz, Flatbush Mural (detail), 2017.

This is language you meet with your body, just as a kid leafs through a Marvel comic not quite bothering to read the captions and word balloons, letting the figures speak instead. Or like a whole train platform of morning commuters covertly gasping, thrilled or outraged by what’s just rolled in, the dream news from the night kitchen.

Katie Merz paints on buildings. Though it might appear more as though she’s peeled off their skin, to reveal networks of information agitating beneath.

Katie is another pure product of Dean Street. I don’t know when we first met, only that we knew immediately that we shared a subway stop, and a nervous system.

Like a few others, she figured out how to get paid to shout back in paint, or at least not get arrested. Not getting arrested: nice work if you can get it.

Katie Merz, Flatbush Mural, 2017.

Katie Merz, Flatbush Mural, 2017.

With The Flatbush Mural, she threatened to cover the city, or at least paint a whole street. The canvas is bigger than your eye—like an IRT train rolling through the station of your mind, only you provide the locomotion.

Katie Merz, Sneakers, 2015.

Katie Merz, Sneakers, 2015.

If you fear you might need special flâneur’s equipment to conduct this survey, Katie Merz has what you need. With these, you can break off a decorated chunk of the city with which to hightail it from the authorities.

Katie Merz, Loved What This Was, c. 2015.

Katie Merz, Loved What This Was, c. 2015.

Another Katie Merz artwork lives in my house. Painted on celluloid, as if waiting to be animated (though it is already animated), Loved What This Was renders a gnomic dream of Henry Miller’s Black Spring, or a film by Ralph Bakshi or a Philip Guston canvas, yet squeezed through the aperture of an ancient Bazooka Joe comic—something you’d find crumpled up on the sidewalk, and smooth out with your thumbs, squinting at the gnarled-up smears of language, trying to get the joke. But the joke is on you.

Katie Merz, Loved What This Was (detail), c. 2015.

Katie Merz, Loved What This Was (detail), c. 2015.

There it goes again, the voice in my mind, the voice of the street. Human cypher, human scribble, human dream.

Blake Lethem BYI (Brooklyn Youth Idols), (detail) 2023. Spray enamel on canvas, 72 x 98

Blake Lethem BYI (Brooklyn Youth Idols), (detail) 2023. Spray enamel on canvas, 72 x 98

__________________________________

From Cellophane Bricks: A Life in Visual Culture by Jonathan Lethem. Copyright © 2024. Available from ZE Books.