English Wikipedia contains almost seven million articles. That is an astonishing fact. And a revealing one, too. Please keep it in the back of your mind as you read on.

As I’ve mentioned before, I’m now co-writing a book with Jimmy Wales, the founder of Wikipedia. The book is about trust and its heart will be the story of Wikipedia – how immense numbers of volunteers created the largest encyclopedia in history and how that encyclopedia became a globally trusted source of information. In fact, I wrote most of this article sitting in a hotel room in Katowice, Poland, while attending this year’s “Wikimania,” the annual global conference of “Wikipedians,” the volunteers who edit Wikipedia.

I am not a Wikipedian. I’m an observer. And what I observe is that hardcore Wikipedians – the sort of people who spend their precious summer holidays attending a conference of Wikipedians — are some of the loveliest people I’ve ever met. Which really isn’t a surprise. After all, these are people who spend enormous amounts of spare time researching, editing, discussing, organizing, working on IT, resolving disputes, and doing the many other tasks required to build and run Wikipedia. And they do it all for free. They don’t even get so much as a byline. Or a “thanks” from the billions of people – yes, billions – who benefit from their labours. Their motivations? It’s mostly curiosity, generosity, and community. These are people who absolutely love finding and sharing knowledge. In a word, these people are nerds. I adore them.

But if you spend time perusing very online American right-wing commentators, that may not be the image you have of the people behind Wikipedia.

Instead, you probably picture weedy youngsters with blue hair, nose rings, and a snarl. Each carries a well-thumbed copy of Das Kapital in a backpack, along with Antifa leaflets and sticks of dynamite. That’s because, while most of the planet sees Wikipedia as a generally reliable source for basic facts on everything from Ansel Adams to ZZ Top, it is increasingly conventional wisdom in much of the American right that, while Wikipedia was once the crown jewel of the Internet, it has been taken over by leftist cadres hell-bent on pushing a neo-Marxist agenda. Wikipedia is now “Wokepedia,” a leftist propaganda platform.

The case against Wikipedia has been percolating for years but several iterations of it have appeared recently. This is the latest version, published a couple of weeks ago. It follows on this critique published last month on Substack. (Note: Please see the PS as the end of the essay.) And this analysis, published by the Manhattan Institute, a conservative American think tank. Conservatives have been using the portmaneau “Wokepedia” for some years now but it was Elon Musk tweeting that accusation to his immense right-wing following that really popularized it. And given that Musk thinks “wokeness” is a “mind virus,” and nothing less than a threat to civilization, calling Wikipedia “Wokepedia” is something more than the gentle punning criticism it may appear.

Maybe all that was inevitable.

For a frightening number of Americans, everything is political, and everything that is political can be divided into “for us” and “against us.” This is true on the right and the left, but I do think the process is at least somewhat asymmetrical, with the right — or at least the very online Musk-worshipping right — going further in the belief that anything not avowedly for us is against us. Do I exaggerate? Consider that, last year, a wide swathe of the American right convinced itself that a pop star (Taylor Swift) dating a football player (Travis Kelce) was all part of an elaborate conspiracy to rig the Super Bowl and maximize the publicity impact when Swift endorsed Joe Biden. Yes, adults of sound mind actually said that. In public. And not only Alex Jones fans. Promoters of this theory included Vivek Ramaswamy, then a Republican presidential contender, now a favourite of Elon Musk, J.D. Vance, and Donald Trump.

Given this background, given Wikipedia’s immense readership, and given the demonstrable trust most people feel for Wikipedia as a source of basic facts, it’s remarkable Wikipedia was not dragged into this hyperpoliticized madness years ago.

Or maybe I’ve got this all wrong.

Maybe Wikipedia really is controlled by leftists hell-bent on promoting a neo-Marxist agenda — leftists who are brilliant at pretending to be apolitical nerds when strangers attend their conventions.

How should we judge? Well, rational people judge claims based on evidence. You are doubtless a rational person. So let’s have a look at the evidence.

As far as I can make out, there are several types of evidence offered by those who claim “Wikipedia is Wokepedia.”

The first involves anecdotes about Wikipedia editors behaving badly. You can find a story or two like that in the articles linked above.

I could get deep into the weeds of those anecdotes and try to test the he-said-she-said veracity of the accusations in each, but I don’t think that’s actually necessary. Instead, I’ll be charitable: I will simply assume that everything in those stories is a full, fair, and accurate description of the events described.

Now, what should we make of that evidence? Does it add up to a damning indictment of Wikipedia?

No. Not remotely.

English Wikipedia is immense. It has — remember! — almost seven million articles! That is a number so huge it can be hard to really grasp what it means. So try this: Picture a complete set of Encyclopedia Britannica on the shelf at your local library. Now picture ninety sets of those books filling shelf after shelf, aisle after aisle. That’s how big English Wikipedia is.

If one editor among the vast throng of editors that created and maintains Wikipedia behaved badly … so what?

Or two editors. Three editors. Four editors. It makes little difference. As scientists say, always a little wearily, the plural of “anecdote” is not “data.”

Condemning Wikipedia as a whole for the bad behaviour of this or that editor is almost as dumb as insisting that the crimes of Bernie Madoff and Jeffrey Epstein prove the United States is a horrid place full of criminals.

The most that this sort of evidence can prove is that Wikipedia is imperfect. But no sane person has ever claimed that Wikipedia is flawless. Wikipedia certainly contains errors and nonsense. I’m pretty sure that if I had asked people at that Wikipedia conference if Wikipedia is perfect, the answer would invariably be a loud guffaw. No one knows Wikipedia’s flaws and failings better than the people who spend their free time finding, arguing about, and correcting those flaws and failings. And I’m confident not one of them expects to ever run out of work.

It is axiomatic, I believe, that every human is biased and every human institution imperfect, and I doubt I’d find any serious Wikipedian who disagreed. (Which is curious because human perfectibility – here comes New Soviet Man! — was a belief of Communists.)

So I think we can dispense with “editors behaving badly” stories and move on to the second sort of evidence brought by Wikipedia’s accusers.

It is institutional evidence. That most recent story exemplifies it.

The article’s headline is a little strange and requires some translation. It reads: How the Regime Captured Wikipedia. What “regime”?

“Regime” is New Right jargon for the supposed cultural elites who control universities and governments and major corporations and Hollywood and the World Economic Forum and The New York Times and so on down the list of institutional elites. In New Right-world, this disparate group isn’t disparate at all. All these seemingly different parts are manifestations of a leftist cultural elite that is highly coordinated and uses its power to promote its worldview and agenda. J.D. Vance is a big fan of this thinking. You can read more about the New Right and the long historical tradition it draws on in the house organ of The Regime. (That’s The New York Times, of course. Curiously, hardcore progressives often loudly despise the Times. That fact would complicate the New Right’s take on the Times if the New Right deigned to notice it.)

The thesis of the article is summed up in its subhed: “Inside the cultural revolution at Wikipedia, which pivoted from a decentralized database of all the world’s knowledge to a top-down social activism and advocacy machine.”

To understand what is being claimed, you need some basic facts: “Wikipedia” is the website you know and read. It is entirely written and edited by volunteers. The “Wikimedia Foundation” is a non-profit foundation created to support Wikipedia (and related projects). It has a substantial budget, endowment, and paid employees, and it provides services like lawyers and core IT support without which Wikipedia could not function. What the Wikimedia Foundation does not do is write and edit articles on Wikipedia. I can’t stress that enough. Wikipedia’s content – the stuff people like you and me care about – is written and controlled by Wikipedia volunteers. It was that way from day one. It still is.

The bulk of that article attacking Wikipedia is devoted to the Wikimedia Foundation’s fundraising, plans, projects, and spending. I’m told by people who should know that its account contains serious mistakes. But you know what? That’s irrelevant for present purposes. Because — let me say it again — the Wikimedia Foundation does not write and edit articles. Wikipedia’s volunteers do. Period.

Now, to be fair, in that article, the author alleges there was an instance where someone with a foot in both camps helped get the Foundation to interfere in the operation of Wikipedia, arguably improperly. I have not investigated that incident so I have no opinion about what did or did not happen, or its propriety. But again, let’s generously assume that what is alleged happened exactly as described. What does that evidence amount to? Yes! It’s another anecdote.

Maybe you think it’s an appalling anecdote that reflects badly on those involved. That’s fine. Let’s go with that. It’s appalling. But remember that fact right at the start of this article? Yeah. Wikipedia is so vast that one appalling incident of misbehaviour is not dissimilar to one person pissing in the ocean. Or, if you think that metaphor understates the seriousness of the anecdote, let me try another: It is one sewage pipe emptying into the ocean. That’s bad. But it does not change the ocean.

Maybe you cringe at scatalogical metaphors. Fine, try this: The tens of thousands of editors who made and make Wikipedia are volunteers. They are independent. They do not take orders from the Wikimedia Foundation. So even if we assume the Wikimedia Foundation really is the incorrigible den of Trotskyite perfidy portrayed in the article, how exactly does that turn Wikipedia into a “top-down advocacy machine”? The argument makes no sense on its face.

Your honour, I move to dismiss the case.

No, hang on. Got carried away. We’re not done yet.

There is one final sort of evidence used to indict Wikipedia.

This evidence is decidedly not anecdotal. And it does not rely on a misleading conflation of the Wikimedia Foundation and Wikipedia. Instead, it uses real techniques of social science. That study by the Manhattan Institute is arguably the best of its kind, and it is more than worthy of serious consideration. So let’s give it that.

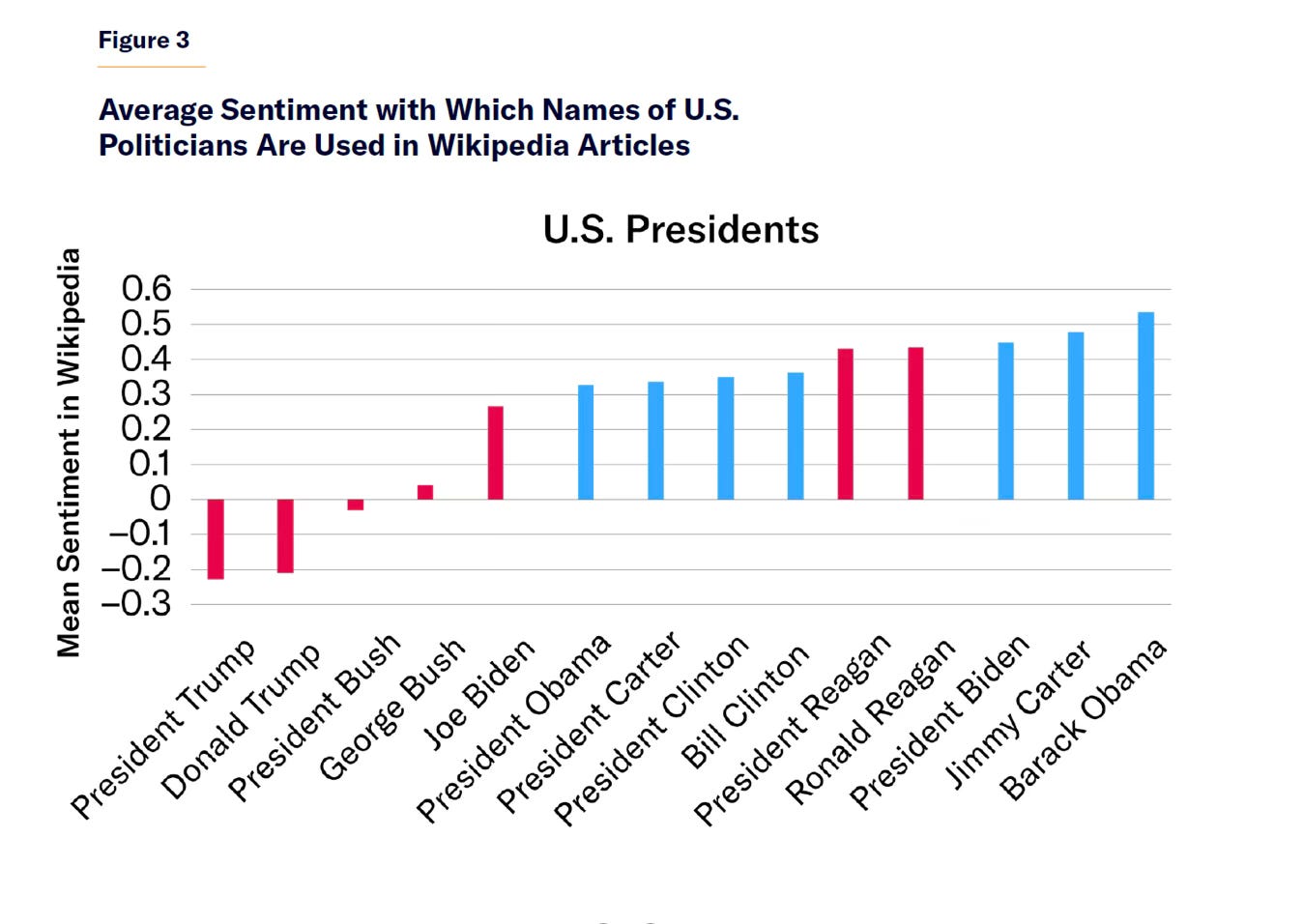

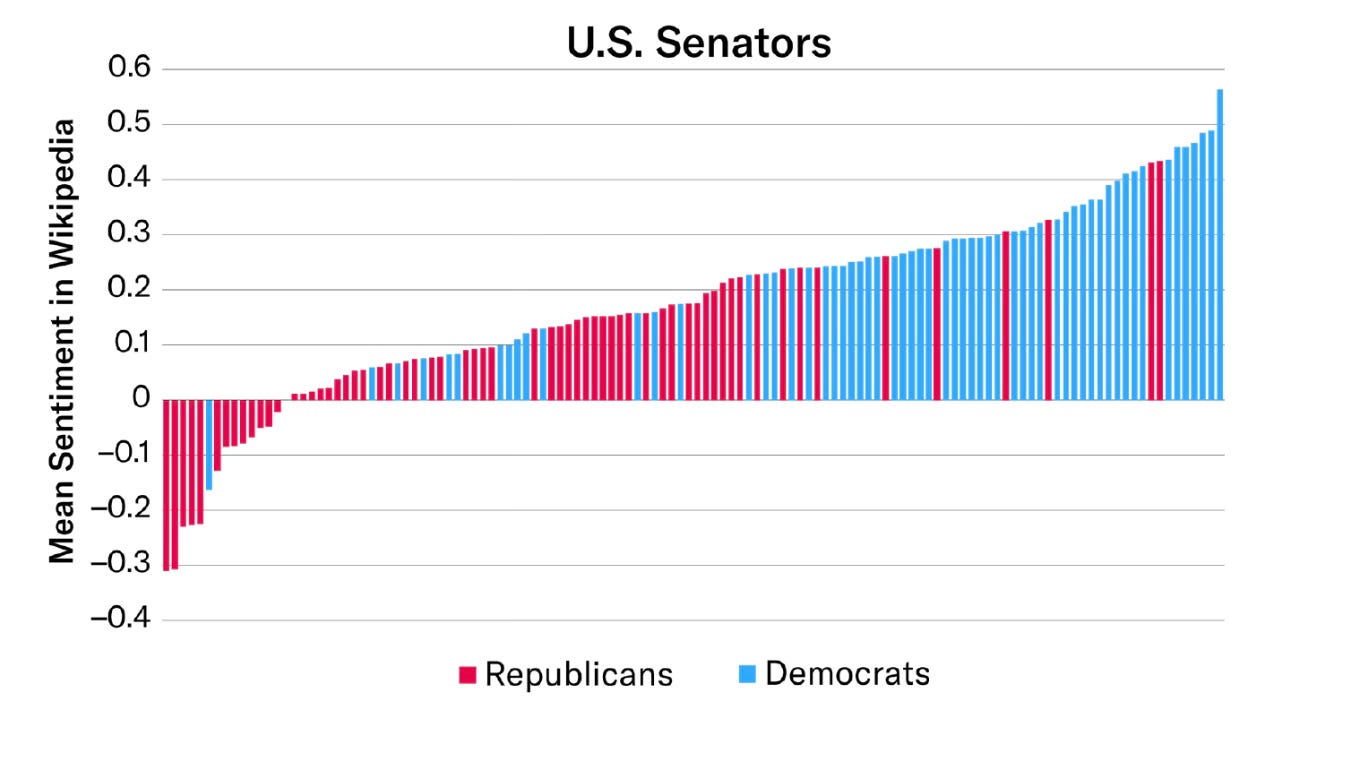

“To study political bias in Wikipedia content,” the study reports, “we analyze the sentiment (positive, neutral, or negative) with which a set of target terms (N=1,628) with political connotations (e.g., names of recent U.S. presidents, U.S. congress members, U.S. Supreme Court justices, or prime ministers of Western countries) are used in Wikipedia articles.”

This is called “sentiment analysis.” It’s a legitimate technique that can be quite useful. It allows researchers to judge the emotional range of language used in a discussion of a subject. The emotional scales — which words are said to contain positive or negative sentiment — are not determined by the researchers in any particular instance but have previously been developed and validated by other research. So this study is not something cooked up to come to a pre-determined conclusion.

So what did the researcher, David Rozado, find when he looked at the sentiments in Wikipedia’s articles? Presented visually, his results are quite striking.

With a quick eyeball of those graphs (and there are several more like them) it seems that articles about left-leaning politicians contain more positive language, while articles about right-leaning politicians have more negative sentiment.

Sounds bad, doesn’t it?

Following is the author’s own summary. (David Rozado is the only author. I have no idea why he uses “we.”)

We find a mild to moderate tendency in Wikipedia articles to associate public figures ideologically aligned right-of-center with more negative sentiment than public figures ideologically aligned left-of-center.

These prevailing associations are apparent for names of recent U.S. presidents, U.S. Supreme Court justices, U.S. senators, U.S. House of Representatives congressmembers, U.S. state governors, Western countries’ prime ministers, and prominent U.S.-based journalists and media organizations.

This trend is common but not ubiquitous. We find no evidence of it in the sentiment with which names of U.K. MPs and U.S.-based think tanks are used in Wikipedia articles.

We also find prevailing associations of negative emotions (e.g., anger and disgust) with right-leaning public figures; and positive emotions (e.g., joy) with left-leaning public figures.

These trends constitute suggestive evidence of political bias embedded in Wikipedia articles.

I’ve seen a lot of people citing this study. And in particular, I’ve seen those charts being waved about on social media like a bloody shirt.

The Regime has been exposed! Wikipedia is Wokepedia!

The first thing to note about that buzz is the discrepancy between what people in the Musk-o-sphere are saying and what the author says. The former are strident and sweepingly dismissive about Wikipedia. But that’s not the language of the researcher himself. Remember, he only claims to have found a “mild to moderate tendency.” And note also that, as the author found — and the Musk-o-sphere ignores — there was no skew found in the articles about UK politics or US-based think tanks. If The Regime is using Wikipedia to promote the left and vilify the right, it’s doing a shit job.

But that’s a minor comment about the discourse surrounding the study. Now let’s look directly at the results: Has this study demonstrated there is a “mild to moderate” bias in favour of the left, and against the right, in many of Wikipedia’s political articles?

I don’t think so. In fact, I think this study is irredeemably flawed — because it rests on a methodological assumption that, I will argue, is simply wrong.

To spot it, take a look at the result for the Wikipedia articles about Ronald Reagan on the chart above.

They tilt strongly positive. In fact, writing about Reagan on Wikipedia has the fourth-highest positive sentiment of all the modern presidents.

Does that mean Wikipedia editors are biased in favour of Ronald Reagan? By the logic of this study, the answer has to be “yes.” After all, that’s the same logic the author uses to conclude that, overall, Wikipedia is biased positively for Democrats and negatively for Republicans.

Hence, if this study is providing real, meaningful insight, we must conclude that Wikipedia is biased against Republicans but for Ronald Reagan.

Does that make even a scrap of sense? Ronald Reagan wasn’t just any old Republican president. He was, and is, the patron saint of the modern Republican Party.

Isn’t that odd? And by “odd,” I mean “absurd.”

It makes no damned sense.

So what’s really going on? I believe the problem lies in the fact that the author has confused “sentiment” and “stance.”

I’ll use Reagan to explain the difference.

Ronald Reagan’s whole political persona was sunny optimism. He was the “morning in America” guy, the “shining city on a hill” man. As a result, almost any article about Reagan would use a lot of words and phrases like “sunny optimism” — words and phrases with strongly positive sentiment. That would be true of even the most neutral articles. Indeed, someone who absolutely despised Reagan, but wrote a basic factual outline of his life and political career, would have no choice but to use lots of words and phrases like “sunny optimism” because that language and attitude is how Reagan won elections and because that’s how people routinely talked about Reagan. But that language would not reflect the author’s stance on Reagan — that is to say, his strongly negative view of Reagan. It would simply reflect the factual reality of Reagan’s life and career.

“Sentiment” is the emotional valence of the words in an article, whether positive, negative, or neutral. “Stance” is the view of the author about the subject of the article. They are not the same. In fact, they are fundamentally different.

If I were to write an article about the fall of the Confederacy and Sherman’s “March to the Sea,” when a Union Army swept through Georgia, looting and burning as it went, that article would be stuffed with negative sentiment. It would have to be. After all, Sherman’s march involved war, killing, death, burning, and destruction. That’s all saturated with negative sentiment.

Now imagine you run my article through a sentiment analysis. Huge negativity! Conclusion? By the logic of this study, it’s obvious: “The author of the article is biased against the Union and General Sherman.”

But I’m not! I hate the Confederacy! I completely and passionately support Sherman and what he did because I think that, as brutal as it was, it was just and necessary to hasten the defeat of the South, the end of the war, and the end of slavery. These views constitute my “stance” on the matter. But by drawing conclusions based on a sentiment analysis — that is, by treating sentiment as synonymous with stance — a researcher could “objectively prove” that I am biased in favour of the Confederacy. Pretty silly, no?

Here’s another way to think about it: Imagine the most scrupulously neutral article about the political career of Donald Trump. It just states facts. No opinion whatsoever. It is perfectly, purely neutral. But if you run it through a sentiment analysis, it would come out strongly negative. Why?

In part because Donald Trump was impeached twice, charged with many crimes, convicted of some, and stands accused of inciting an insurrection. And that’s only a partial list of what he’s been accused of. There’s also fraud, sexual assault, rape. And more. Whatever you think of the substance of the accusations, they have been made. So if you are writing a scrupulously neutral, factual article about Donald Trump, you would have to list them. And guess what? All those words have negative sentiment attached. Run that through a sentiment analysis and the conclusion, by this study’s logic, is that you are biased against Donald Trump. Even though your article is absolutely neutral.

Let’s take this a step further. Imagine you are a writer who is passionately pro-Trump. You want to support Trump by writing a sympathetic biography of his political career. Of course you think all the accusations levelled at Trump are illegitimate. So you write about them, explaining why you think they are illegitimate. And guess what? If you run your article through a sentiment analysis it will come out strongly negative — because it is stuffed with words like “fraud” and “riot” and “insurrection” and “rape.” By the logic of this study, your writing would biased against Donald Trump — even though you passionately support him!

Then there’s Trump’s political persona, which is the polar opposite of Ronald Reagan’s. Where Reagan loved to talk about the sunlit future, Trump always goes on about decline and despair. Trump talks so relentlessly about crime and disease and corruption and war and rigged elections, that one of his routine references in stump speeches is Hannibal Lecter. Seriously, Hannibal Lecter, also known as “Hannibal the Cannibal.” I’m pretty sure “cannibal” codes negative in sentiment analysis. Any attempt to describe Trump and his political career would reflect all of that. There’s no way around it. If you ran Donald Trump’s own presidential inaugural address — the one famously containing the phrase “American carnage” — through a sentiment analysis, it would generate off-the-charts negative sentiment. If you then wrote a scrupulously neutral description of that address, it, too, would score high on negative sentiment — but that would not prove the author is biased against Trump.

OK, that’s enough. Maybe too much. I’m sure you get the point: Sentiment is not stance. This study conflates the two, so it proves nothing.

By the way, if you think this is just Dan Gardner ginning up a methodological criticism to knock down a study whose conclusions he doesn’t like, think again: Here is an academic study published two years ago making exactly my argument. Its title is “Sentiment Is Not Stance.”

In closing, let’s recap the evidence that Wikipedia has become “Wokepedia.”

First, some anecdotes that do not — cannot — prove much.

Second, criticism about a different organization that says little or nothing about Wikipedia.

Third, a text-based data analysis which, although well-intentioned, is fundamentally misguided and misleading and fails to support its supposed conclusions.

And that’s it.

Your honour, I move to dismiss the case.

Particularly in the United States, these are hyper-politicized times. (See Taylor Swift, above.) This atmosphere leads people to zero in on political matters, often to the exclusion of all else. That’s unfortunate for a number of reasons, not the least of which is what it causes us to overlook.

When Jimmy Wales founded Wikipedia, he said it would become “the sum of all human knowledge.” It’s not. But that’s a push goal. And while Wikipedia does not contain everything, it is, in fact, the biggest encyclopedia in human history. By a huge margin. Did I mention English Wikipedia alone contains almost seven million articles?

That is a towering achievement. It is something to celebrate. And be inspired by. Look what people can accomplish when they freely come together and create!

But instead of celebrating Wikipedia, lots of people are bitching and moaning about “Wokepedia” — because they think a very small subset of those seven million articles are politically biased.

Even if they were — and please do show me better evidence than you have so far — would that be reason to denigrate and sweepingly dismiss the entirety of one of humanity’s greatest constructions? I don’t think so.

Reality is so much bigger than politics. And so is Wikipedia.

PS (added August 27): A reader brought to my attention that my first reference to this essay by Tracing Woodgrains could be read to mean I am including the author and his essay among those making the case that Wikipedia has become “Wokepedia.” On reflection, I think that’s right. I regret that. So let me clarify.

In my reading, that essay only examines the behaviour of one editor. While I think its conclusion is hyperbolic — “the site lives under the shadow of Gerard’s deadly gaze…” — the essay is clearly of a different species than the crude attacks on “Wokepedia.” In fact, one could argue it’s very much in the spirit of Wikipedia, as it identifies what it argues is a problem and urges correction. Agree or not with its conclusions, that sort of searching criticism is core to how Wikipedia became as good as it is.

So why did I include it in that list? Because when it was published on Substack, a veritable parade of Substackers — including quite a few big names who really should know better — lined up not only to applaud the author and condemn the criticized editor, but to wave that essay like a bloody shirt and make outlandish statements dismissing Wikipedia as nothing more than leftist propaganda.

I don’t know the author but I suspect, and hope, that was not his intention.

In sum: I included that essay because it has been widely cited by the “Wikipedia is Wokepedia!” crowd as proving their charge. (It does not and cannot.) I did not include it to suggest that was the author’s argument or intention.