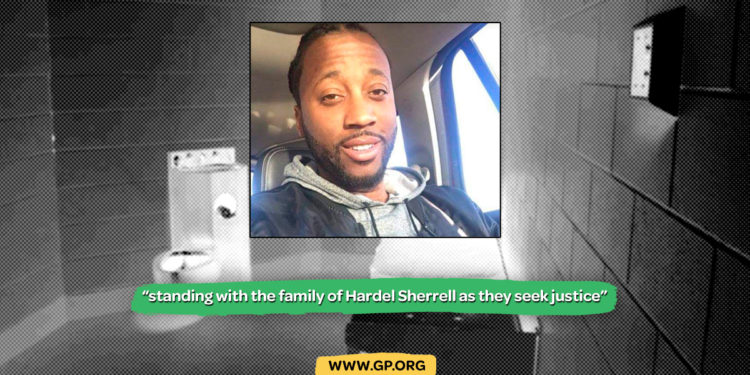

UPDATE: Dr. Leonard’s medical license is suspended indefinitely following a ruling made by the Minnesota Medical Board. In a 164-page document, the State included details of Hardel Sherrell’s grueling death to justify their decision. I first reported on this injustice two years ago with Niko of Unicorn Riot. We were first to publish the harrowing jail footage that was used as evidence to prove the medical neglect of Dr. Leonard and others working for his company MEnD correctional care inside the Beltrami County Jail where Hardel died 9 days after he arrived. He informed the guards and medical staff that he needed medical attention but he was told he was “faking it”. His mother Del Shea Perry has fought relentlessly for this decision and also got the Hardel Sherrell Act passed in 2021. Perry also filed a lawsuit claiming wrongful death, medical malpractice, and constitutional rights violations. Her son died from Guillain-Barré syndrome which is a treatable condition. Hardel Sherrell, 27, died Sept. 2, 2018.

Bemidji, MN – Shocking jail surveillance footage shows days of medical neglect that led to 27-year-old Hardel Sherrell’s death inside of Beltrami County Jail last September. Del Shea Perry, Hardel’s mother, recently filed a lawsuit against Beltrami County and dozens of other defendants, claiming medical negligence in the wrongful death of her son, who died while in jail from Guillain-Barré Syndrome.

Hardel, a father to three daughters, was in jail on a gun charge and awaiting court proceedings. He was transferred from Dakota County Jail to Beltrami County Jail on August 24, 2018.

He died in a jail cell nine days later.

During his incarceration, doctors, nurses, and correctional officers all assumed Hardel was “faking it” in his requests for medical care. He repeatedly reached out to ask for medical treatment as his body was shutting down due to an undiagnosed Guillain-Barré, a rare syndrome that attacks one’s nervous system.

ardel was the third death at Beltrami County in three years. He was preceded in death by 39-year-old Stephanie Bunker, who died in 2017 after attempting suicide, and 26-year-old Tony May, Jr., who suffered sudden cardiac arrest and death in August 2016.

In Bunker’s case, Beltrami County was found to have violated state rules on inmate welfare checks.

herrell’s cause of death was listed as pneumonia by the Ramsey County Medical Examiner. However, an independent autopsy found that Mr. Sherrell died from Guillain-Barré Syndrome.

Perry has filed a lawsuit in Minnesota District Court claiming medical malpractice, wrongful death, and constitutional rights violations.

Hardel Sherrell was a young Black man locked up in Northern Minnesota facing possible prison time. This wasn’t his first time dealing with jails and the court system; his mom said he was eager to get back to his three children and was ready to do the time.

However, this time Hardel’s incarceration turned tragic. As undiagnosed Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) quickly wreaked havoc deteriorating and paralyzing Hardel’s body, those put in charge of his well-being didn’t seem to care.

Hardel was told he was faking his illness and was held back from outside medical care for fear of escape.

Once he got to a hospital for tests, doctors were unable to diagnose Hardel. They agreed with corrections officers that he was “faking” his suffering and had him sent back to jail, where he died a day later.

Hardel’s story is a microcosm of the bias that African Americans face in institutions across the USA, including medical systems both inside and outside of jails and prisons.

What is Guillain-Barré Syndrome?

Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) is a neurological disorder that causes the immune system to attack one’s body and nervous system. GBS causes a range of symptoms including mild weakness, pain including severe deep muscle pain, difficulty with eye muscles, impaired vision, and difficulty swallowing, speaking and chewing. It can also cause abnormal heart rate and blood pressure, a prickling sensation in one’s hands and feet, and in extreme cases, total paralysis.

The cause of GBS is unknown, although researchers do not believe the condition is inherited or contagious.

There is currently no known cure for GBS. Treatment options include plasma exchange and high-dose immunoglobulin therapy. When treated within the first two weeks of symptoms, seven out of ten individuals make a full recovery, although 30 percent will continue to have symptoms for up to three years following successful treatment.

According to the lawsuit filed, “the existence of Guillain-Barré Syndrome is well-known to primary care and emergency physicians and nurses because it occurs after common viral infections.”

Tragic Timeline

After Sherrell’s death on September 2, 2018, his mother Del Shea Perry, and her legal team were able to get several videos from Beltrami County Jail. Six videos were given to Unicorn Riot: two from Sherrell’s first two days, and four from his final two days.

Along with the surveillance videos, her legal team acquired notes from the correctional officers’ jail logs, as well as from those who provided medical care to Sherrell in Minnesota, Bemidji and Fargo.

Perry’s legal team then used all of the evidence gathered to create a harrowing timeline of Sherrell’s nine days in Beltrami County Jail, which can be read in the lawsuit and seen in the videos.

After being transferred from Dakota County, Sherrell can be seen in a Beltrami County Jail elevator dated August 24, 2018. In the video, Sherrell was shackled yet able-bodied and could be seen smiling and conversing with a corrections officer.

The next day he was seen on video actively standing and walking around, playing cards with fellow inmates.

Hardel Sherrell’s medical kite asking for a visit to the hospital on August 28, 2018

During the night of August 28, Sherrell submitted another medical kite, this time asking to be taken to the hospital, saying he could no longer feel his legs.

The next morning, he was put in a wheelchair and taken to a medical segregation cell. His blood pressure had risen to 162/116.

Notes from Sherrell’s time in medical segregation suggest the jailers continually believed he was “just fine.” Meanwhile, Sherrell could no longer swallow, so he couldn’t eat anything. He could barely use his arms and struggled to sit up.

He called his mother the next day and told her about the “ridiculous” amount of pain he was in, saying that he’d “rather roll over and die.” He said, “I need to see a specialist” because “they cant help me in here.”

By August 30, 2018, Sherrell couldn’t feel anything below his waist and his face was noticeably drooping. His blood pressure was 168/109, even though he had been taking antihypertensive medications. After seeing him around 7:40 a.m., the jail nurse ordered him to be taken to an emergency room immediately.

Later that afternoon the emergency room medical orders were canceled. Beltrami County Jail Administrator Calandra Allen, who is named in the lawsuit, overrode the jail nurse’s medical order, saying that she believed Sherrell was likely just “trying to escape.”

“Defendant Allen stated that she was given information that Mr. Sherrell may be trying to escape.” — Beltrami Co. Jail Administrator Calandra Allen overrides emergency room medical order for Sherrell, page 10 of lawsuit against Beltrami County, et al.

Sherrell’s condition continued to worsen. The next morning he was sent for tests at the hospital in Bemidji, MN. From there he was brought to Sanford Medical Center Fargo in North Dakota for a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) test.

Dr. Dustin Leigh examined Sherrell. According to the lawsuit, despite the loss of reaction to painful stimuli and other sensations, visible facial droop, and extremity weakness, Dr. Leigh determined Sherrell was “faking/lying.” He gave the transport jailers discharge orders to bring Sherrell back to jail.

“Dr. Leigh ignored Mr. Sherrell’s symptoms and determined that Mr. Sherrell was faking/lying.” — Sanford Medical Center Doctor Dustin Leigh misdiagnoses Sherrell, page 11 of lawsuit against Beltrami County, et al.

After being delivered back to jail from a day of testing and transporting, Sherrell still couldn’t feel his legs, and couldn’t get himself out of the vehicle and onto his wheelchair.

In an exchange seen through video and described by Del Shea in our exclusive sit-down, four correctional officers (co-defendants in the lawsuit) allowed Sherrell to fall out of the police SUV. As they picked him up to set him in his wheelchair, they let him drop face-down on the garage floor where he stayed for several minutes.

A correctional officer can be seen pushing Sherrell’s head forward after it flopped back, as officers used a wheelchair to bring him back inside the jail.

The mistreatment Sherrell suffered only got worse from there.

The next video is from the medical segregation cell that he was brought to. It shows Sherrell, still shackled and unable to walk, being dragged and dropped haphazardly onto a cell mat by three jailers. His left arm can be seen dangling off the cell bunk, his legs extending over the edge; he barely moved.

About two hours after being laid on his mat, a struggling Sherrell seemed to be seizing or attempting to move his arm and fell face-down onto the floor. There he laid face-down on the floor, paralyzed and “to suffer without assistance” for nearly eight hours, alleges the lawsuit.

“It was clear that his weakness had become much worse and that he was paralyzed and no longer able to use any part of his body in a coordinated way, which was a new development as of his return from the hospital early in the morning.” — page 13 of lawsuit against Beltrami County, et al.

The day that Sherrell died in his jail cell, he received little attention. He laid on the floor of his cell with small sporadic hand or arm movements.

Sherrell’s medical discharge orders sent with the jailers instructed them to seek immediate medical attention at the “nearest emergency department, if any of the following occurs…

- “Signs of stroke (paralysis or numbness on one side of the body, drooping on one side of the face, difficulty talking).”

- “Worsening of weakness, difficulty standing, paralysis, loss of control of the bladder or bowels or difficulty swallowing.“

There is a record of how those medical orders came to be disobeyed.

The morning of September 1, a corrections officer advised a nurse that Sherrell had told him that he couldn’t feel his legs nor move his extremities. Instead of checking on the inmate, the nurse reviewed the jail’s records on him and told corrections officer Melissa Bohlmann that there was “nothing medically wrong with him.”

Officer Bohlmann relayed to Beltrami County Jail Administrator Allen what the nurse had told her, to which Allen responded, “if medical states there is nothing wrong… then go with it.” Sherrell became incontinent that day, releasing his bowels and bladder, and was not able to eat or drink. He is seen on video trying in vain to move his fingers and arms to reach the liquid tray brought to his cell.

That night, when speaking about Sherrell during an evening briefing between jailers, corrections officer Melissa Bohlmann told other staff, “medical stated that we didn’t need to assist him with anything as there was nothing medically wrong with him and he was capable of doing it himself.”

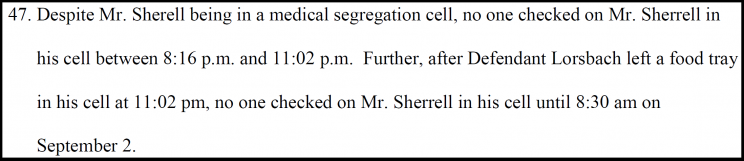

Despite being in medical segregation with noticeably plummeting health, Sherrell was essentially abandoned in his cell with no medical care for 12 hours between 8 p.m. on September 1, and 8 a.m. on September 2.

Nurse Michelle Skroch saw Sherrell the morning of September 2. Skroch was the same nurse who had claimed the day before that there was “nothing medically wrong with him” after reviewing his patient file in lieu of personally checking in on him.

According to the lawsuit, Skroch’s Sept. 2 examination of Sherrell concluded with her telling staff to make sure they used a straw when feeding him.

Hardel Sherrell’s final hours were spent in the depths of neglect. Though his paralysis had progressed deeply, none of the correctional staff at Beltrami County Jail, nor any of the nurses and health care workers from MeND Correctional Care, followed any of the hospital’s medical discharge orders.

He died in the Beltrami County Jail in medical segregation cell 215, around 5 p.m. on September 2, 2018.

Del Shea Perry said that she saw the video of her son dying and chose not to allow the video to be released.

“It was like everybody’s moving in slow motion to help him. I’m going to leave it at that. He died in a cold jail cell on the floor. He may have died in a hospital, which would have been a little more dignity, you know, would have given him hope that maybe somebody was trying to help him. They didn’t care. They knew that he wasn’t faking it. They just didn’t care.” — Del Shea Perry, about watching the video in which her son dies in a jail cell

“I know that I’ll be reunited with him in heaven. I miss my baby so much.”

Belabored with grief, Del Shea Perry described her only son, Hardel Sherrell, as a “momma’s boy” with an incredible sense of humor. She said that “his laughter filled the room” and it “was so contagious.”

Even in difficult times, Del Shea says her son was optimistic.

“He loved to make people laugh. Had a huge heart. Loved his little girls and his family. Was crazy about his momma. Unfortunately he made some mistakes. It cost him his life.” — Del Shea Perry, Hardel Sherrell’s mother

Del Shea says the loss of her son doesn’t leave a void in only her life but is “indescribable” for her three granddaughters as well.

“These little girls will have several birthday parties without their father celebrating it with them, graduation ceremonies will happen without their father being there, they will one day get married without their father being able to walk them down the aisle. It’s not fair.” — Del Shea Perry, Hardel Sherrell’s mother

Del Shea said that she is not suing for money as “no amount of money can replace my only child.” She said that the others who have lost their loved ones in Beltrami Co. are not in it for money either; they want Beltrami County Jail investigated and shut down. “We can’t afford to lose another life,” Perry said.

Unicorn Riot’s Hardel Sherrell Coverage:

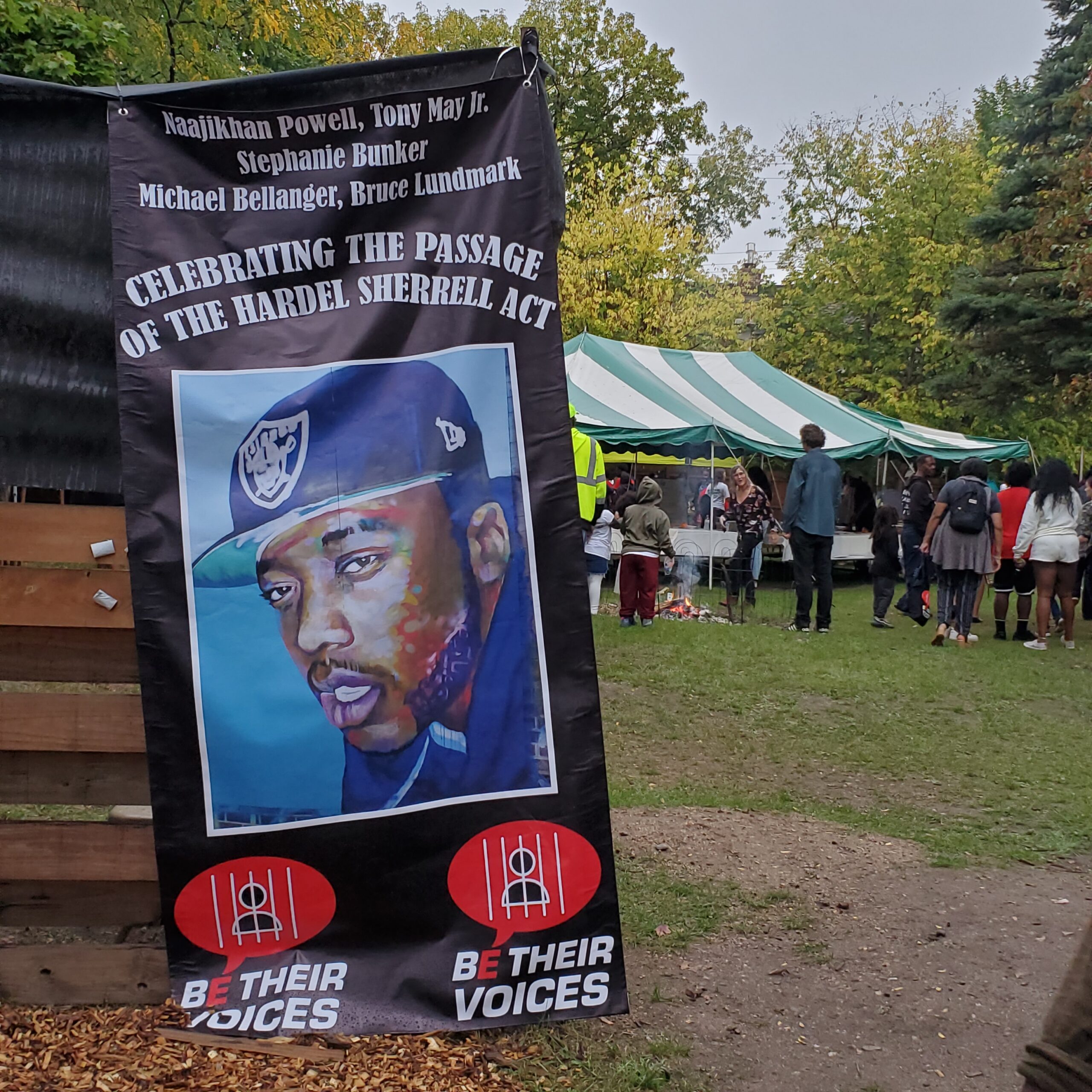

This past Saturday on Saint Paul’s Selby Avenue community members celebrated the passage of reforms to improve safety and standards for people in Minnesota jails. The legislation – passed in June – is named in honor of Hardel Sherrell who died after medical neglect at the Beltrami County jail in 2018.

“For the governor to sign the Hardel Sherrell Act into law lets us know that protest works, that prayer works and that faith works. And that fighting works, too,” said Sherrell’s uncle Trahern Crews, who also leads Black Lives Matter Minnesota. “And that you can’t give up, and we have to keep fighting for justice.”

Among other things, the bill establishes standards around mental health and medical care, and outlines policies around the death of individuals in custody.

After being prompted by Sherrell’s family to reinvestigate, the Minnesota Department of Corrections found evidence of “regular and gross violations in jail standards.” Video footage and medical records revealed that the 27-year-old had told prison guards and medical providers he was in excruciating pain on numerous occasions over the course of several days. His condition deteriorated to paralysis. A witness nurse confirmed that, even after his death, medical providers claimed he had been faking his illness.

In the aftermath, Sherrell’s mother Del Shea Perry started the nonprofit Be Their Voices.

“I felt like I was in this alone,” she said. “And I was like, ‘who dies in jail? Where do they do that at?’ And I thought to myself, ‘Am I the only one that’s going through this?’ Well, I found out real quick I wasn’t.”

Last year, a KARE 11 investigation found there have been at least 50 deaths in Minnesota jails since 2015.

Photo Credits: Feven Gerezgiher