Now A fractured country.

Then

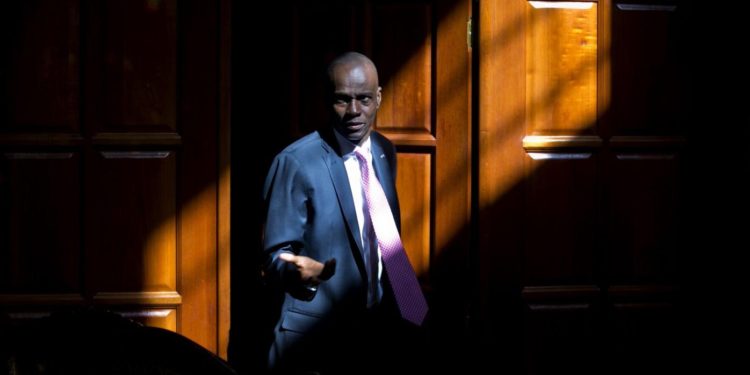

The assassination of Haitian President Jovenel Moïse has drawn shock and condemnation from leaders in other parts of the world, along with calls for calm and unity in Haiti.

Moïse was killed in an attack on his private residence early Wednesday, according to Haiti’s interim prime minister. First lady Martine Moïse was shot in the attack and is hospitalized. It wasn’t immediately clear who was behind the assassination in the troubled Caribbean nation, which has grown increasingly unstable in recent years.

“We are shocked and saddened to hear of the horrific assassination of President Jovenel Moïse and the attack on the first lady Martine Moïse of Haiti. We condemn this heinous act,” U.S. President Joe Biden said in a statement. “The United States offers condolences to the people of Haiti, and we stand ready to assist as we continue to work for a safe and secure Haiti.”

Colombian President Iván Duque described the assassination as a “cowardly act” and also expressed solidarity with Haiti. He called for an urgent mission by the Organization of American States “to protect democratic order.”

Marlene Bastien, the executive director of Family Action Network Movement, a group that assists residents in Miami’s Little Haitian community, said the “next few days are going to be very chaotic and contentious” as government supporters and opponents jostle for power.

“There is definitely a constitutional crisis and political void right now,” said Bastien.

“People are scared about tomorrow,” she said.

Bastian called on the Biden administration to take an active role in efforts to hold free, fair, and credible elections in Haiti, following the assassination of Moïse who had been ruling by decree.

“Here is a chance to do it right from the start,” said Bastien. “No more Band-aids. The Haitian people have been crying and suffering for too long.”

In Boston, which has one of the largest Haitian communities in the U.S., a pastor who heads a Haitian advocacy group, Dieufort Fleurissaint, said he’s worried about reprisals and further unrest.

Fleurissaint said he’s been checking in with family, friends, and fellow pastors in Haiti since the early hours to make sure everyone stays at home for now.

He said his regular Wednesday morning prayer call with pastors in Haiti and the U.S. was inevitably focused on the killing.

“They’re afraid for their lives,” Fleurissaint said. “The situation is dire. We’re praying for peace in Haiti.”

Leaders across the world voiced fears that the assassination could lead to more unrest.

The European Union’s foreign policy chief, Josep Borrell, warned in a tweet that “this crime carries a risk of instability and (a) spiral of violence.”

British Prime Minister Boris Johnson tweeted: “This is an abhorrent act and I call for calm at this time.”

Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez condemned the assassination.

“I’d like to make an appeal for political unity to get out of this terrible trauma that the country is going through,” Sánchez said during a visit to Latvia.

France’s Foreign Affairs Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian said he was stunned by “this despicable assassination” and urged those involved in Haiti’s political life to “show calm and restraint.”

In a written statement, Le Drian advised French citizens in Haiti to exercise the utmost caution.

Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen offered her condolences via Twitter.

“We wish the first lady a prompt recovery, & stand together with our ally Haiti in this difficult time,” Tsai wrote. Haiti is one of only a handful of countries that maintain formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan, which China claims as its own.

Call me a conspiracy theorist and maybe that is true but it seems that strong black leaders have untimely demise especially the ones that are real men; the Lybian Leader wrote to Obama was mind-blowing and Lybia went from being one of the most stable countries to one where people are killing people and slavery is alive and well. Every black leader that stands up in our country or any other, someone comes up dead. Martin Luther King was killed by our government, Fred Hampton, and Malcolm X coincidence or just the way the ball bounces. The letter is clear the Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi knew he was going to die.

The following is the text of a letter sent to President Barack Obama on Wednesday by Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi, published by the Associated Press news agency. The misspellings and grammatical errors are in the original letter.

Our son, Excellency,

President Obama

U.S.A

We have been hurt more morally than physically because of what had happened against us in both deeds and words by you. Despite all this, you will always remain our son whatever happened. We still pray that you continue to be president of the USA.

We Endeavour and hope that you will gain victory in the new election campaign. You are a man who has enough courage to annul a wrong and mistaken action. I am sure that you are able to shoulder the responsibility for that. Enough evidence is available, Bearing in mind that you are the president of the strongest power in the world nowadays, and since Nato is waging an unjust war against a small people of a developing country.

This country had already been subjected to embargo and sanctions, furthermore, it also suffered a direct military armed aggression during Reagan’s time. This country is Libya. Hence, to serving world peace … Friendship between our peoples and for the sake of economic, and security cooperation against terror, you are in a position to keep Nato off the Libyan affair for good. Obama was convinced by Hillary Clinton that it would end up like Rwanda that Bill Clinton ignored. No Obama cause the country to become way more unstable with Qaddaffi gone. It has not recovered yet

You – yourself – said on many occasions, one of them in the UN General Assembly, I was witness to that personally, that America is not responsible for the security of other peoples. That America helps only. This is the right logic.

Our dear son, Excellency, Baraka Hussein Abu Obama, your intervention is the name of the U.S.A. is a must, so that Nato would withdraw finally from the Libyan affair. Libya should be left to Libyans within the African union frame.

The problem now stands as follows:-

1. There is Nato intervention politically as well as military.

2. Terror conducted by Al Qaueda gangs that have been armed in some cities, and by force refused to allow people to go back to their normal life, and carry on with exercising their social people’s power as usual.

Mu’aumer Qaddaffi

Leader of the Revolution

Tripoli 5.4.2011

At the end of August 2011, the BBC published the musings of its diplomatic editor, Mark Urban, on what future interventions in troubled countries would look like.

At the time, the former Libyan leader, Muammar al-Gaddafi, had been ousted in a violent uprising inspired by the Arab Spring and Western interests. France, the US, and the UK had been more than helpful in striking at Gaddafi loyalists.

Urban’s write-up was a fairly monotonic piece but not in a boring way. It read as you would expect the educated opinions of a person who knows wars and some peace.

But Urban is only a man in the media, the fourth estate of the modern democratic establishment capable of just about anything if there is space.

The man who embodies so much of this esteemed detachment, with particular regards to Libya, is Barack Obama.

If there was a man who could afford to lead the offensive in Libya and look forward to another war like tomorrow is Tuesday, that was Obama.

In April of 2016, Obama said “failing to plan for the day after” the ousting Gaddafi was the worst mistake of his presidency. However, he had no regrets about intervening in Libya because it “was the right thing to do”.

Obama was pedantic in that interview, making sure he separated two things. He was a noncommital repenter, seeking the absolution he would not say sorry for.

That is the detachment he could afford. There was no sword of Damocles swinging around his head threatening to come down when things go wrong.

There is no denying that there was to Gaddafi’s overthrow, an organic and populist call. Indeed Gaddafi’s life had been in danger courtesy the venom of his own people since the 1980s.

In 1998, he survived one of the many attacks on his life by Arab militia thanks to the storied bravado of one of his revolutionary nuns who was killed in the attack.

A famously paranoid man, Gaddafi prioritized the advancement of his tribesmen, family, and those loyal to him. His son, Khamis, led an army brigade, supposedly an avant-garde foil for any military coups.

Gaddafi treated his enemies from cities such as Dayda, Berna, and Benghazi, most of them perceived, with very little humanity.

It was estimated that before the uprising, one in three Libyans was not a satisfactory beneficiary of the massive returns in the country’s energy sector.

If one was looking for material to convict the idea that Gaddafi had to go, there was something. But logically, that state of affairs does not consist of permissions to the NATO intervention.

Some say the severity of the matter in 2011 called for Western bombs. Except the problem is that after World War II, Western “wars of freedom” outside Europe have not delivered as advertised.

In the trend of tradition, Obama’s after-Gaddafi plan was that there was no plan after Gaddafi.

It might not be Obama’s personal wish to leave the Libyan people headless and in a situation where human traffickers would have a field day. But his office gave him the right.

In the months leading up to the coalition that went into Libya, the UK, France, and the US threw around the necessary rhetoric and the actions synonymous with “we are very concerned”.

It was not until February 2011 that then French president, Nicolas Sarkozy, decided that Gaddafi must go.

Between Sarkozy’s declaration and August 2011, about 20 countries had contributed to the muscle, machines, and money to make the inevitable happen. There was not a single accord on how to not repeat the miseries of Iraq and Afghanistan that had happened just in the previous decade.

That problem was Libya’s.

Urban even wrote in that BBC piece: “There are good reasons why Libya should be able to pull itself up in the coming months – not least the positive spirit, and yearning for democracy…”.

Libya was avoidable for Obama, a man enamored with history and the symbolism of change. He could have negotiated a better alternative because at least, that is what he promised to be all about.

Leading the most powerful country in the world against a problematic dictator, Obama was well in the opposition to have sought a practical democratic experiment after the war.

And he knew he was going to be held to account on what happens after wars.

Speaking to The Atlantic in 2016, Obama’s former deputy national security advisor, Ben Rhodes, noted this culture of accountability his former boss took: “If you were to say, for instance, that we’re going to rid Afghanistan of the Taliban and build a prosperous democracy instead, the president is aware that someone, seven years later, is going to hold you to that promise.”

What we saw with Libya was a sketchily similar promise without using the words.

In announcing America’s participation in the coalition efforts, Obama said “we are protecting the Libyan people from Gaddafi’s forces” and “putting in other measures to avoid further atrocities….as part of a larger strategy to support the Libyan people.”

He was quick to add that the US’s role was minor and praised “more nations, not just the United States, bearing the responsibilities and cost of upholding peace and security.”

The logic here was not dissimilar to the confession in 2016. The hesitation was in there and so was the temptation to own up – a rather perfect blend of plausible deniability.

This was the detachment Obama could afford. It is believable that he does regret what has become of Libya but it is equally valid to say he was not thinking much about that when he signed the US up for the war.

And that is one of the blots he has to live with.

Libya’s ongoing destruction belongs to Hillary Clinton more than anyone else. It was she who pushed President Barack Obama to launch his splendid little war, backing the overthrow of Moammar Gaddafi in the name of protecting Libya’s civilians. When later asked about Gaddafi’s death, she cackled and exclaimed: “We came, we saw, he died.”

Alas, his was not the last death in that conflict, which has flared anew, turning Libya into a real‐life Game of Thrones. An artificial country already suffering from deep regional divisions, Libya has been further torn apart by political and religious differences. One commander fighting on behalf of the Government of National Accord (GNA), Salem Bin Ismail, told the BBC: “We have had chaos since 2011.”

Arrayed against the weak unity government is the former Gaddafi general, U.S. citizen, and one‐time CIA adjunct Khalifa Haftar. For years, the two sides have appeared to be in relative military balance, but a who’s who of meddlesome outsiders has turned the conflict into an international affair. The latest playbook features Egypt, France, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Russia supporting Haftar, while Italy, Qatar, and Turkey are with the unity government.

In April, Haftar launched an offensive to seize Tripoli. It faltered until Russian mercenaries made an appearance in September, bringing Haftar to the gates of Tripoli. He apparently is also employing Sudanese mercenaries, though not with their nation’s backing. Now Turkey plans to introduce troops to bolster the official government.

Washington’s position is at best confused. It officially recognizes the GNA. When Haftar started his offensive, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo issued a statement urging “the immediate halt to these military operations.” However, President Donald Trump then initiated a friendly phone call to Haftar “to discuss ongoing counterterrorism efforts and the need to achieve peace and stability in Libya,” according to the White House. More incongruously, “The president recognized Field Marshal Haftar’s significant role in fighting terrorism and securing Libya’s oil resources, and the two discussed a shared vision for Libya’s transition to a stable, democratic political system.” The State Department recently urged both sides to step back. However, Haftar continues to advance, and just days ago captured the coastal city of Sirte.

In recent years, Libya had been of little concern to the U.S. It was an oil producer, but Gaddafi had as much incentive to sell the oil as did King Idris I, whom Gaddafi and other members of the “Free Officers Movement” ousted. Gaddafi carefully balanced interests in Libya’s complex tribal society and kept the military weak over fears of another coup. He was a geopolitical troublemaker, supporting a variety of insurgent and terrorist groups. But he steadily lost influence, alienating virtually every African and Middle Eastern government.

Of greatest concern to Washington, Libyan agents organized terrorist attacks against the U.S.—bombing an American airliner and a Berlin disco frequented by American soldiers—leading to economic sanctions and military retaliation. However, those days were long over by 2011. Eight years before, in the aftermath of the U.S. invasion of Iraq, Gaddafi repudiated terrorism and ended his missile and nuclear programs in a deal with the U.S. and Europe. He was feted in European capitals. His government served as a non‐permanent member of the UN Security Council from 2008 to 2009. American officials congratulated him for his assistance against terrorism and discussed possible assistance in return. All seemed forgiven.

Then in 2011, the Arab Spring engulfed Libya, as people rose against Gaddafi’s rule. He responded with force to reestablish control. However, Western advocates of regime change warned that genocide was possible and pushed for intervention under United Nations auspices. In explaining his decision to intervene, Obama stated: “We knew that if we waited one more day, Benghazi…could suffer a massacre that would have reverberated across the region and stained the conscience of the world.” Russia and China went along with a resolution authorizing “all necessary measures to prevent the killing of civilians.”

In fact, the fears were fraudulent. Gaddafi was no angel, but he hadn’t targeted civilians, and his florid rhetoric, cited by critics, only attacked those who had taken up arms. He even promised amnesty to those who abandoned their weapons. With no civilians to protect, NATO, led by the U.S., bombed Libyan government forces and installations and backed the insurgents’ offensive. It was not a humanitarian intervention, but a lengthy, costly, low‐tech, regime‐change war, mostly at Libyan expense. Obama claimed: “We had a unique ability to stop the violence.” Instead his administration ensured that the initial civil war would drag on for months—and the larger struggle ultimately for years.

On October 20, 2011, Gaddafi was discovered hiding in a culvert in Sirte. He was beaten, sodomized with a bayonet, shot, and killed. That essentially ended the first phase of the extended Libyan civil war. Gaddafi had done much to earn his fate, but his death led to an entirely new set of problems.

A low level insurgency continued, led by former Gaddafi followers. Proposals either to disband militia forces or integrate them into the National Transitional Council (NTC) military went unfulfilled, and this developed into the conflict’s second phase. Elections delivered fragmented results, as ideological, religious, and other divisions ran deep. Militias were accused of misusing government funds, employing violence, and kidnapping and assassinating their opponents. Islamist groups increasingly attempted to impose religious rule. Violence and insecurity worsened.

In February 2014, Haftar challenged the General National Congress (GNC). Hostilities broadly evolved between the GNC/GNA, backed by several militias, which controlled Tripoli and much of the country’s west, and the Tobruk‐based House of Representatives, which was supported by Haftar and his Libyan National Army. Multiple domestic factions, forces, and militias also were involved. Among them was the Islamic State, which murdered Egyptian Coptic (Christian) laborers.

The African Union and the United Nations promoted various peace initiatives. However, other governments fueled hostilities. Most notable now is the potential entry of Turkish troops.

In mid‐December, Turkey’s parliament approved an agreement to provide equipment, military training, technical aid, and intelligence. (The Erdogan government also controversially set maritime boundaries with Libya that conflict with other claims, most notably from Cyprus, Egypt, Greece, and Israel.) Ankara introduced some members of the dwindling Syrian insurgents once aligned against the Assad regime to Libya and raised the possibility of adding its “quick reaction force” to the fight.

At the end of last month, the Erdogan government introduced, and parliament approved, legislation to authorize the deployment of combat forces. President Erdogan criticized nations that backed a “putschist general” and “warlord” and promised to support the GNA “much more effectively.” While noting that Turkey doesn’t “go where we are not invited” (except, apparently, Syria), Erdogan added that “since now there is an invitation [from the GNA], we will accept it.”

But Haftar refused to back down. Last week, he called on “men and women, soldiers and civilians, to defend our land and our honor.” He continued: “We accept the challenge and declare jihad and a call to arms.”

Turkish legislator Ismet Yilmaz supported the intervention and warned that the conflict might “spread instability to Turkey.” More likely the intervention is a grab for energy, since Ankara has devoted significant resources of late to exploring the Eastern Mediterranean for oil and gas. Libya has oil deposits, of course, which could be exploited under a friendly government. Perhaps most important, Ankara wants to ensure that its interests are respected in the Eastern Mediterranean.

However, direct intervention is an extraordinarily dangerous step. It puts Turkey in the line of fire, as in Syria. Ankara’s forces could clash with those of Russia, which maintains the merest veneer of deniability over its role in Libya. And other powers—Egypt, perhaps, or the UAE—might ramp up their involvement in an effort to thwart Erdogan’s plans.

In response, the U.S. attempted to warn Turkey against intervening. “External military intervention threatens prospects for resolving the conflict,” said State Department spokeswoman Morgan Ortagus with no hint of irony. Congress might go further: some of its members have already proposed sanctioning Russia for the introduction of mercenaries, and Ankara has few friends left on Capitol Hill. Nevertheless it is rather late for Washington to cry foul. Its claim to essentially a monopoly on Mideast meddling can only be seen as risible by other powers.

The Arab League has also criticized “foreign interference.” In a resolution passed in late December, the group expressed “serious concern over the military escalation further aggravating the situation in Libya and which threatens the security and stability of neighboring countries and the entire region.” However, Arab League is no less hypocritical. Egypt, the UAE, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia, all deeply involved in the conflict, are members of the league. And no one would be surprised if some or all of them decided to expand their participation in the fighting. Egyptian president Abdel Fatah al‐Sisi insisted: “We will not allow anyone to control Libya. It is a matter of Egyptian national security.”

Although the fighting is less intense than in, say, Syria, combat has gone high‐tech. According to the Washington Post: “Eight months into Libya’s worst spasm of violence in eight years, the conflict is being fought increasingly by weaponized drones.” ISIS is one of the few beneficiaries of these years of fighting. GNA‐allied militias that once cooperated with the U.S. and other states in counterterrorism are now focused on Haftar, allowing militants to revive, set up desert camps, and organize attacks. Washington still employs drones, but they rely on accurate intelligence, best gathered on the ground, and even then well‐directed hits are no substitute for local ground operations.

The losers are the Libyan people. The fighting has resulted in thousands of deaths and tens of thousands of refugees. Divisions, even among tribes, are growing. The future looks ever dimmer. Fathi Bashagha, the GNA interior minister, lamented: “Every day we are burying young people who should be helping us build Libya.” Absent a major change, many more will be buried in the future.

Yet the air of unreality surrounding the conflict remains. In late December, President Trump met with al‐Sisi and, according to the White House, the two “rejected foreign exploitation and agreed that parties must take urgent steps to resolve the conflict before Libyans lose control to foreign actors.” However, the latter already happened—nine years ago when America first intervened.

The Obama administration did not plan to ruin Libya for a generation. But its decision to take on another people’s fight has resulted in catastrophe. Hillary Clinton’s malignant gift keeps on giving. Such is the cost of America’s promiscuous war‐making.