Connie Chung’s career began with an entrance: “I barged into a local TV station, [said], ‘I can learn. I don’t have experience, but I can do this job.’ … You know when you’re young and you don’t know any better? I just plowed forward as if I knew what I was doing.”

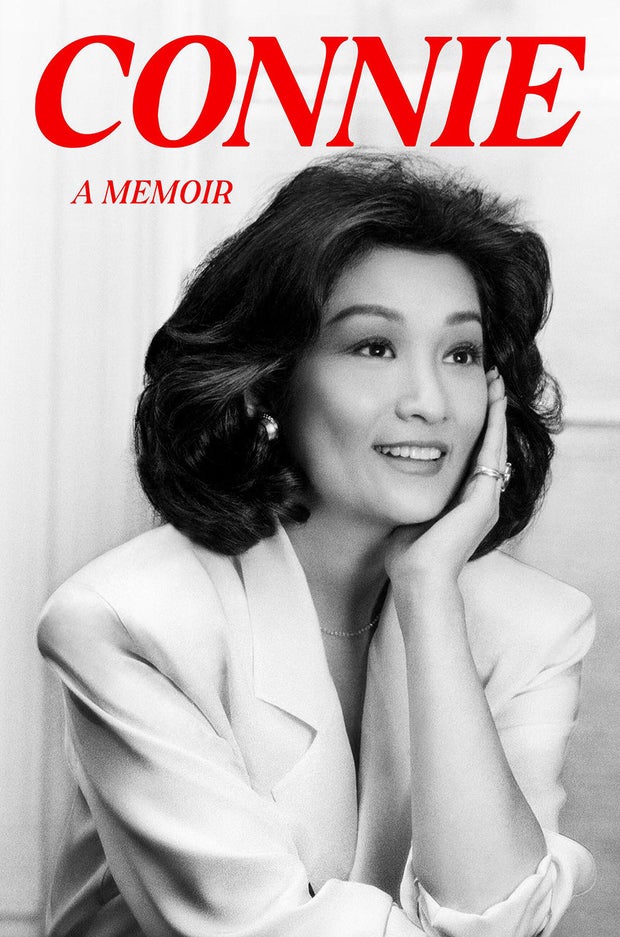

And as she writes in her new memoir, “Connie” (to be published Tuesday), nobody was going to outwork Connie Chung.

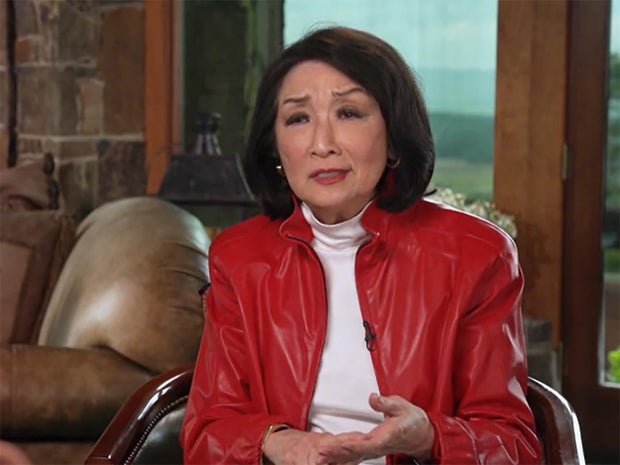

At home in Montana, with her husband of nearly 40 years, daytime TV legend Maury Povich, she can enjoy the view, and reflect on a four-decade career.

Grand Central Publishing

Povich, who was then a rising star in the newsroom, recalls: “She wanted a job, and the news director said, ‘No, no, no, you’re my assistant.’ She says, ‘No, I want that job, weekend writer on the news desk.’ And he said, ‘Well, then you have to replace yourself.’ She walks out of the newsroom, across the street, into the bank, looks at the first woman teller and says, You wanna be in TV? Marched her across the street into the newsroom. She got the job, and the bank teller got a job as the secretary.”

Soon she caught the eye of CBS News, barging into a restaurant cited for health violations with a camera crew in tow. “Lo and behold, the CBS bureau chief was sitting there having lunch,” Chung said. “He saw me, and he gave me his card, and he said: Call me.”

At the CBS News Washington bureau in 1971, which she characterized as “a sea of men,” Chung devised a survival plan: “I looked around and I said, ‘Well, heck, I’m gonna be a guy, too.’ So, I took on their characteristics. I had bravado; I would walk into a room as if I owned it!”

And she could talk like a sailor. “I had a bawdy reputation for saying the unexpected to these men who were rather sexist and racist. And they were: Whoa! But the bad words? Not good. I don’t recommend that to anyone. It was just my MO of how to survive in that snake pit.”

White House photo, courtesy Nixon Presidential Library and Museum

Moving up one step at a time wasn’t enough for Chung. When NBC wanted to hire somebody to present the half-hour of news before the “Today” show, Chung said, “I’ll do that! But I also want to not just do that; I want to report political stories for Tom Brokaw’s ‘Nightly News.’ And I want to do the ‘Saturday Night News.’ And I’d like to do ‘Newsbreaks’ at 9 and 10 p.m. That made it very difficult to sleep.”

Pauley asked, “You seem to be a powerful hybrid of your American-ness and your Chinese. American, opportunity; Chinese?”

“Dutiful,” said Chung. “Always does the right thing. Goody two-shoes. Respectful.”

“Ambition? Drive? Focus?”

“Yeah, sure, sure,” Chung replied. “The drive to succeed. That was a combo platter.”

NBC News

In hypercompetitive network battles, the prize interview was The Get. In November 1991, Magic Johnson, the great L.A. Lakers point guard, revealed that he had tested positive for HIV. Chung said, “I went to his agent’s office and squatted. I wouldn’t leave until he left the office.” She got the interview.

She also got the first interview with the captain of the Exxon Valdez, after the devastating Alaska oil spill.

But while the Tonya Harding skating scandal and documentaries with titillating titles (“Life in the Fat Lane”) delivered ratings, the taint of tabloid fare sullied her name and reputation.

“It was story after story after story, and I just did not have the power to say no,” Chung said. “And I so regret that, Jane.”

CBS News

The daughter of “very, very traditional” Chinese immigrants, Connie was the youngest of five sisters, the only one born in America. Her father decided she would be the son he never had, and carry on the Chung name.

She exceeded his expectations, and realized her own dream, joining Dan Rather as co-anchor on the “CBS Evening News” in 1993.

But it was not the dream team. She recalled the line from the Bette Davis movie, “All About Eve”: “She’s going up the steps, and she says, ‘Fasten your seat belts, it’s going to be a bumpy night.’ And I thought: Yup! Hang on, honey!”

After two years, she was fired. She was, she said, “absolutely crushed.”

But then, just days later, after years of miscarriages and infertility treatments, their adopted son was born. “We got Matthew when he was less than a day old,” Chung said. “He never left my arm, you know? He was an extension of my arm. And to this day, he’s a grown man, and so wonderful.”

At the age of 49, Connie Chung almost had it all, admitting, “I could never declare success. I was born Chinese. I’m born humble. Never enough.”

According to Povich, it took the “Connie Generation” for her to realize exactly what she had become.

Last year, The New York Times published a story entitled “Generation Connie,” about Chinese, Korean and Japanese parents across the country naming their baby daughters after her.

“I couldn’t believe it,” said Chung. “It was the most exhilarating day that I could have ever imagined. It was they who declared me a success. And once they did that, I thought, Really? I have to accept that.“

WEB EXTRA: Connie Chung on being a role model (YouTube Video)

Pauley asked, “What did you mean to their parents?”

“Work hard, be brave and take risks,” said Chung. “I wasn’t the smartest. I wasn’t the toughest. But those three things, I did.”

READ AN EXCERPT: “Connie: A Memoir” by Connie Chung

For more info:

Story produced by Jay Kernis. Editor: Mike Levine.

See also: