Walking out for his first Grand Slam final at age 19, Carlos Alcaraz bumped fists with fans leaning over a railing along the path leading to the Arthur Ashe Stadium court. Moments later, after the coin toss, Alcaraz turned to sprint to the baseline for the warm-up, until being beckoned back to the net by the chair umpire for the customary pre-match photos.

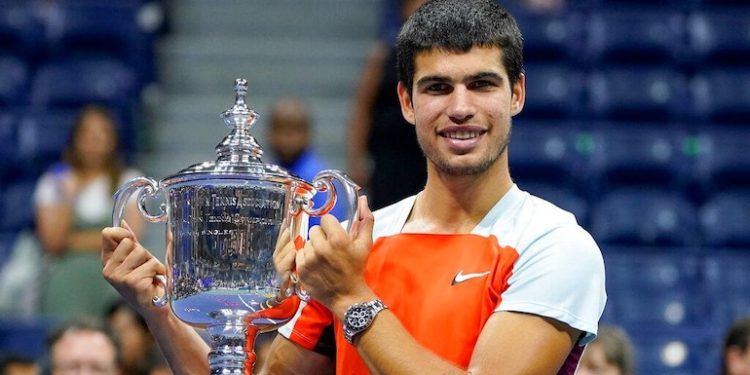

Alcaraz is imbued with boundless enthusiasm and energy, not to mention skill, speed, stamina, and sangfroid. And now he’s a US Open champion and the No. 1 player in men’s tennis.

Alcaraz used his combination of moxie and maturity to beat Casper Ruud 6-4, 2-6, 7-6 (1), 6-3 for the trophy at Flushing Meadows on Sunday and become the youngest man to lead the ATP rankings.

“Well, this is something that I dreamed of since I was a kid,” said Alcaraz, whom folks of a certain age might still consider a kid. “It’s something I worked really, really hard [for]. It’s tough to talk right now. A lot of emotions.”

Alcaraz is a Spanish player who was appearing in his eighth major tournament and second at Flushing Meadows but already has attracted plenty of attention as someone considered the next big thing in men’s tennis. He’s the youngest man to win a major title since Rafael Nadal was the same age at the 2005 French Open, and the youngest at the US Open since 19-year-old Pete Sampras in 1990.

“He’s one of these few rare talents that comes up every now and then in sports. That’s what it seems like,” said Ruud, a 23-year-old from Norway. “Let’s see how his career develops, but it’s going all in the right direction.”

Alcaraz was serenaded by choruses of “Ole, Ole, Ole! Carlos!” that reverberated off the closed roof at Arthur Ashe Stadium — and he often motioned to the supportive spectators to get louder.

When We Were Young

Carlos Alcaraz is the youngest player to reach ATP No. 1 since the rankings were introduced in 1973.

| YRS-DAYS | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2022 | Carlos Alcaraz | 19-130 |

| 2001 | Lleyton Hewitt | 20-268 |

| 2000 | Marat Safin | 20-298 |

| 1980 | John McEnroe | 21-16 |

He only briefly showed signs of fatigue from having to get through three consecutive five-setters to reach the title match, something no one had done in New York in 30 years. He spent a total of 23 hours, 40 minutes on the court in the tournament, the most by any men’s player during any one major tournament since the start of 2000.

Alcaraz went five sets against 2014 US Open champion Marin Cilic in the fourth round, ending at 2:23 a.m. Tuesday; against Jannik Sinner in the quarterfinals, a 5-hour, 15-minute thriller that ended at 2:50 a.m. Friday after Alcaraz needed to save a match point, and against Frances Tiafoe in the semifinals.

“You have to give everything on the court. You have to give everything you have inside. I worked really, really hard to earn it,” Alcaraz said after the final. “It’s not time to be tired.”

This was not a stroll to the finish, though.

Alcaraz dropped the second set and faced a pair of set points while down 6-5 in the third. But he erased each of those point-from-the-set opportunities for Ruud with the sorts of quick-reflex, soft-hand volleys he repeatedly displayed. And with help from a series of shanked shots by a tight-looking Ruud in the ensuing tiebreaker, Alcaraz surged to the end of that set.

“He just played too good on those points. We’ve seen it many times before: He steps up when he needs to,” Ruud said. ‘When it’s close, he pulls out great shots.”

One break in the fourth was all it took for Alcaraz to seal the victory in the only Grand Slam final between two players seeking both a first major championship and the top spot in the ATP’s computerized rankings, which date to 1973.

The winner was guaranteed to be first in Monday’s rankings; the loser was guaranteed to be second.

“Both Carlos and I, we knew what we were playing for. We knew what was at stake,” Ruud said. “I think it’s fitting. I’m disappointed, of course, that I’m not No. 1, but No. 2 is not too bad, either.”

He is now 0-2 in Slam finals after being runner-up to Nadal at the French Open in June.

Ruud stood way back near the wall to return serve, but also during the course of points, much more so than Alcaraz, who attacked when he could. Alcaraz went after Ruud’s weaker side, the backhand, and found success that way, especially while serving.

If nothing else, Ruud gets the sportsmanship award for conceding a point he knew he didn’t deserve. It came while he was trailing 4-3 in the first set; he raced forward to a short ball that bounced twice before Ruud’s racket touched it.

Play continued, and Alcaraz hesitated and then flubbed his response. But Ruud told the chair umpire what had happened, giving the point to Alcaraz, who gave his foe a thumbs-up and applauded right along with the spectators to acknowledge the move.

Alcaraz certainly seems to be a rare talent, possessing an enviable all-court game, a blend of groundstroke power with a willingness to push forward and close points with his volleying ability. He won 34 of 45 points when he went to the net Sunday. He is a threat while serving — he delivered 14 aces at up to 128 mph on Sunday — and returning, earning 11 break points, converting three.

Alcaraz, Ruud said, showed “incredible fighting spirit and will to win.”

Make no mistake: Ruud is no slouch, either. There’s a reason he is the youngest man since Nadal to get to two major finals in one season and managed to win a 55-shot point, the longest of the tournament, in the semifinals Friday.

But this was Alcaraz’s time to shine under the lights.

For context on the rankings, it is helpful to know that Novak Djokovic did not play at the US Open or Australian Open this year, was unable to enter those countries because is not vaccinated against COVID-19, and did not receive any ranking boost for his Wimbledon championship because no points were on offer for anyone after the All England Club banned athletes from Russia and Belarus over the invasion of Ukraine.

Regardless of the circumstances, it is significant that Alcaraz is the first male teenager at No. 1. No one else did it. Not Nadal, not Djokovic, not Federer, not Sampras. No one.

When one last service winner glanced off Ruud’s frame, Alcaraz dropped to his back on the court, then rolled over onto his stomach, covering his face with his hands. Then he went into the stands for hugs with his coach, Juan Carlos Ferrero, a former No. 1 himself who won the French Open in 2003 and reached the final of that year’s US Open, and others, crying all the while.

You get to No. 1 for the first time only once. You win a first Grand Slam title only once. Many folks expect Alcaraz to be celebrating these sorts of feats for years to come.