Can we demand ‘social responsibility’ from art? What “common good” can art in the twenty-first-century offer?

When we discuss art in relation to social responsibility, it seems that we view art from a teleological perspective. Teleology comes from the Greek words “telos”, which means end, purpose, or goal; and “logos”, which means reason, explanation, or study. Teleology is the study of ends and purposes. While some contend that art serves particular social and political objectives, others counter the idea that art can have direct political influence. For instance, according to modern aesthetics, art should be freed from practical concerns to achieve an aesthetic experience.

Art’s domains are in creating different perspective, experience, and meaning. The goal of art is not to directly bring justice or eliminate inequality. Even though art cannot have an immediate impact on social or political issues, that does not mean that art does not have social responsibility.

The term “social responsibility” was adopted from a phrase used by demonstrators in May 1968, who demanded changes in business models and marketing tactics to accommodate social justice better. In an art context, we can pose some questions about art’s social responsibility: Does art have social responsibility? What is art’s social responsibility? How does art contribute its social responsibility?

Art and social responsibility issues are worth discussing since art is shaped by and within society. Art also plays a part in arousing social awareness and influencing society. As quoted from Delia Vekony’s article, art has a role in creating what Catherine Malabou calls “ground-zero.” Ground Zero is an open site, a non-teleological space, without prescriptions and expectations.

We usually live in instrumental rationality in which everything is oriented toward ends. Things are valuable in terms of helping achieve goals. As a result, for example, we are now facing an environmental catastrophe caused by growth-oriented capitalism.

Art can provide “ground zero,” an empty area that allows the emergence of alternative configurations. At ground zero, artwork challenges viewers to reexamine an issue or subject matter without regard to the dominant social paradigm.

Art also has the power to absorb its viewers. The viewer’s experience of the artwork involved more than just their focus and imaginative thinking; they were also completely absorbed and immersed into the art. The viewers step into the new world that happens in their minds (Kees Vuyk, 2015). When someone is in an immersive state, they have the opportunity to view the world and themselves from entirely new angles while yet connecting them to their own experiences.

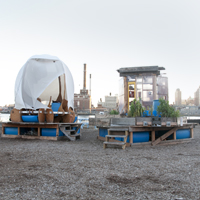

Let’s take an example, Triple Island by Mary Mattingly. It is a flexible, amphibious ecosystem that serves as a temporary home for its inhabitants. The three small temporary residences were built beside the river in Lower Manhattan’s bustling city. Triple Island is a strategy for surviving in New York in the future, where environmental issues are intensifying.

This artwork “throws” us back to ground zero, removing any focus on profit and imagining the future in an apocalyptic environmental catastrophe setting. This piece of art reflects the deep relationship between people and nature.

Mary Mattingly’s Waterfront Development | “New York Close Up” | Art21