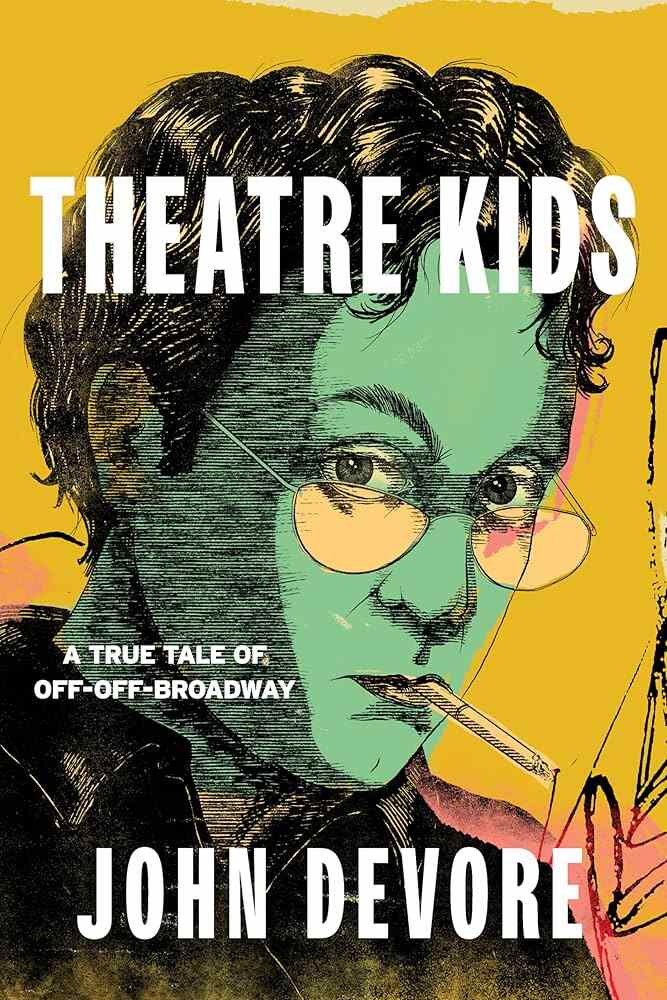

John DeVore and Becky Jollensten McGarity circa 1992.

Lights up on a small theatre in Brooklyn, New York. Enter John DeVore, late 40s. His hair and beard are streaked with gray. He stands in a spotlight centerstage and says:

My name is John, and I’m a theatre kid. I’m a theatre kid the way a raccoon is a raccoon, or a pineapple is a pineapple. I like to think of it as my astrological sign, something about me that is fixed. It is who I am, and I had little choice in the matter.

During one of my very first school plays, a teacher suggested I had been bitten by the acting bug, contracting a virus with no known cure. But I knew better: I had been screaming for attention since I was born. If I could have been the opposite of a theatre kid, I would have. But I can’t be who I’m not. I’m pretty sure the opposite of a theatre kid is a Dallas Cowboys fan.

Being a theatre kid is like that Groucho joke about not wanting to join a club that would have you as a member. That’s my experience, at least. I’ve never been a joiner. If I could change that about me, I would. I want to be loved and left alone at the same time. That is my default setting. My therapist is always telling me to open my heart to other people, and my usual response to his gentle requests is, “I’m trying, Gary.”

I once denied being a theatre kid, a bit like how the apostle Peter repeatedly lied when asked by the mob if he knew Jesus. My denial happened years ago, in the late aughts. 2008? Right before the economy cratered. Those were dark times for me. I had gone on an impromptu weeknight bender with a former colleague—a lonely old journalist with a talent for sniffing out bullshit and a sickening thirst for crème de menthe—who suspected I had acted in high school or college. I just laughed him off. Me? A theatre kid? No.

And my ruse would have worked had we not stumbled, piss-drunk, into a nearly empty karaoke bar and had I not insisted on performing a sloppy, surprisingly poignant rendition of the popular torch song “On My Own” from the blockbuster 1987 Broadway mega-musical Les Misérables—which, if you’re not aware, is a weepy, blood-and-thunder pop opera written by Claude-Michel Schönberg and Alain Boublil and based on Victor Hugo’s 19th-century novel about poor French vagrants suffering beautifully. “On My Own” is sung by the forlorn street waif Eponine, who pines after handsome revolutionary Marius, whose heart in turn belongs to Cosette, the adopted daughter of our hero, ex-convict Jean Valjean. Eponine is a lonely victim of unrequited love, and later she dies in Marius’s arms, fulfilling the deepest, darkest, most pathetic fantasy of anyone who has ever longed for someone they could never have.

My former colleague could see the truth in my tear-filled eyes as I sang with everything I had. I couldn’t help myself. I was feeling it. I sang like I was competing for a Tony Award. I did that thing Broadway divas do where they slowly push one jazz hand toward the heavens as the emotions swell. I was in church, and from the back pew, I could hear him laughing and pointing at me like I was a fool. He knew a theatre kid when he saw one.

Like I said: dark times.

How can you tell if someone you know, or even love, is a theatre kid? Ask yourself this: Do they take a lot of selfies? Do. They. Enunciate. Every. Word? Do they frequently sigh heavily? Do they talk about themselves and their manifold feelings incessantly? These are just a few of the signs. Do they spell it t-h-e-a-t-r-e instead of t-h-e-a-t-e-r? That’s a good one. Only a true theatre kid spells it “theatre.” A “theater” is where you watch “theatre.” You see? No? This difference matters, and if you don’t think it does, you’re probably not a theatre kid, which may come as a relief to many of you.

Now, I need you to know that I know that t-h-e-a-t-r-e is just the British spelling of the word. But I much prefer the other explanation, don’t you? It’s more romantic. The theatre is an ancient art, a sacred, almost holy occupation. It’s a way to teach moral lessons and to celebrate the human condition; it is a story full of sound and fury that can levitate you or knock you sideways. The theatre is a spirit—and the theater is where you sit and cough politely, and then the curtain rises. There might not even be a curtain. A theater can be a space, any space. A storefront, an apartment living room, a parking lot.

This wisdom has been passed down from theatre kid to theatre kid from time immemorial. It was a veteran of my high school’s drama program who taught me the difference between theatre and theater. She was a full year older than me, but she knew things. I thought she was brilliant. I remember listening to her intently: Theatre was life. This lesson probably happened over cups of creamy, sugary coffee and plates of baklava at the local 24-hour diner, where all the theatre kids at my high school would go to celebrate after a successful production—a one-act or the spring musical.

We’d pour into the diner like an army of frogs, laughing and talking a mile a minute and singing show tunes, and the poor servers endured our overbearing youthful cheerfulness. My true theatre education happened either at that diner or backstage, during rehearsal breaks, and these impromptu lectures are the closest thing to an oral tradition in action I’ve ever encountered.

These 16-year-old elders patiently explained the superstitions and rules of the theatre, and I did the same when it was my turn to pass on the lore. I remember the rules like commandments: Never whistle backstage or say the name of Shakespeare’s famous tragedy about that Scottish couple who make a series of poorly thought-out career decisions. Both of those things are bad luck.

Saying “good luck” is also bad luck. You’re supposed to say “break a leg.”

There are all sorts of explanations as to what that phrase means. I was told, over a plate of french fries, that in ye olden times, the mechanism that raised and lowered the curtains was called a leg, and so to break a leg would mean that the audience cheered for so many encores, the curtain went up and down and up and down until it broke. Is that true? I have no idea. That’s just how I heard it.

Here are a few more sacred rules: Give flowers after a performance, not before. Always open the stage door for one of your fellow castmates and invite them to enter first with a graceful bow. One of my favorites warns against putting your shoes on any table backstage. Don’t do that. Why? I don’t think you want to find out.

There were also practical, straightforward rules about rehearsal and being part of a production. Always be on time. (“If you’re 10 minutes early, you’re on time. If you’re on time, you’re late.” That was the mantra. I was told to repeat it and to repeat it.) Don’t skip rehearsal. Memorize your lines. Stretch before every performance, and drink nothing but hot water with lemon juice and honey if you catch a cold. And never, ever become romantically involved with someone in the cast—a rule that was broken during every production at my high school, sometimes multiple times. Show romances were a huge no-no. This rule was meant to keep rehearsals drama-free. But rehearsals are intense and intimate, and it’s almost impossible to keep theatre kids from trying to make out with other theatre kids.

Show romances—also known as “showmances”—were looked down on, even by those who had them. The only exceptions were hookups between cast and crew, which worked in my favor. I will always be a sucker for a girl who can use power tools, because I cannot use power tools, and I fell for stage managers and set builders. A boy never hit on me, but I was ready for it, just in case, and had practiced a flattered, “I like you, but I don’t like-like you” speech in the mirror. I never got to perform that speech, which disappointed me. A few years later, in college, a beautiful man kissed me on the dance floor of a party. It was a deep and playful kiss, and before I could stammer, “I like you, but I don’t…,” he had disappeared into the crowd, and now that I think about it, that was disappointing too.

When I was a senior I gave the newbies at the diner a variation of the speech I was given in ninth grade. It went something like: “Look around at this table. These are the friends you’ll have for the rest of your life.” That wasn’t true, but in the moment it felt true, and that’s good enough. I also passed along to them what was passed to me, from senior to frosh, and that is to always, always attend the closing night cast party, and to stay until the very end.

John is an award-winning writer and editor who lives in Brooklyn with his wife and one-eyed mutt, Morley. His debut memoir, Theatre Kids, was published by Applause Books and came out this summer.