Book Review

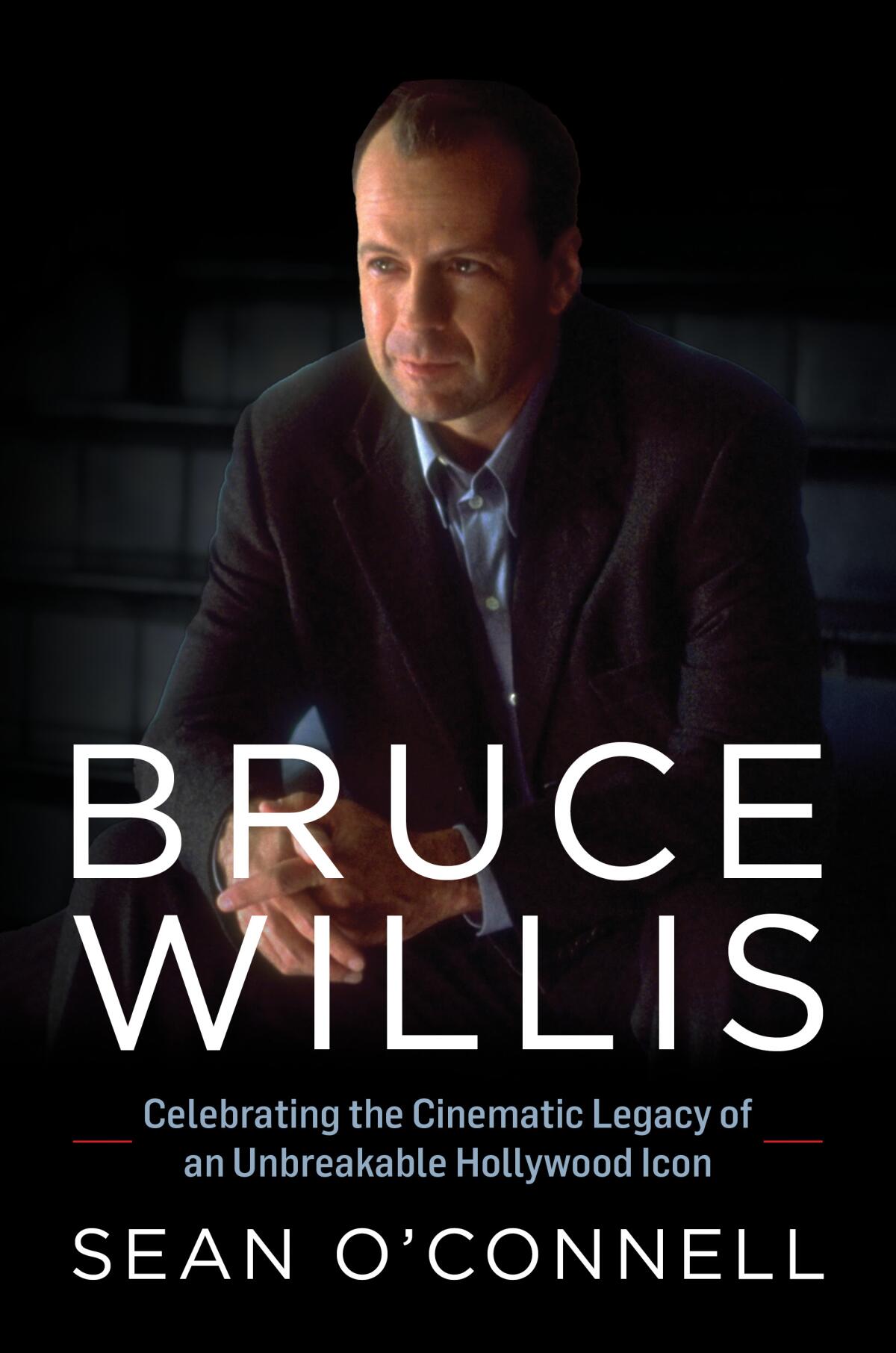

Bruce Willis: Celebrating the Cinematic Legacy of an Unbreakable Hollywood Icon

By Sean O’Connell

Applause Books: 288 pages, $33

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Bruce Willis strutted onto the scene in 1985 as an aggressively charming, motormouth private detective who could talk his way into and out of any scrape presented. Starring opposite Cybill Shepherd in “Moonlighting,” which ran for five seasons on ABC, he was a star from the jump, electrically funny with a hint of the swashbuckling hero he would become a few years later in “Die Hard” (1988).

Unlike fellow action stars (and Planet Hollywood partners) Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone, Willis had range, bopping from blockbusters to comedies to character roles and back again throughout his career. And he did it all with a refreshingly human touch. As Sean O’Connell writes in his new book, “Bruce Willis: Celebrating the Cinematic Legacy of an Unbreakable Hollywood Icon,” Willis showed “that heroes didn’t need to be chiseled from marble to prevail.”

There’s something very sad about referring to Willis, 69, in the past tense, or the arrival of a book that serves as a career retrospective. But that’s where we are. In 2022, Willis announced that he was retiring from acting due to aphasia, which progressed last year to frontotemporal dementia and will eventually claim his life. It’s a horribly cruel way to go — my girlfriend, Kate, died after her steep aphasia descent in 2020 — and it seems even worse when you consider Willis’ prodigious gift of gab, even if some of his best roles — Butch in “Pulp Fiction,” Dr. Malcolm Crowe in “The Sixth Sense” (1999) — were rather stoic.

John Goodman, quoted in the book, knew Willis when the future star was a New York bartender and was certain Willis would be a successful actor just from the way he bantered with customers.

So it’s hard not to read O’Connell’s book as a valediction of sorts, though it is also, as the title suggests, a celebration. The author offers a film-by-film breakdown of Willis’ career, dividing his body of work into categories (including comedies, action movies, sci-fi and the like. The “Die Hard” franchise gets its own section).

O’Connell, a veteran journalist and author, proves a thoughtful guide, and given the circumstances, it’s perfectly understandable if the book can be overly generous (for instance, describing the critical reaction to the 1991 cat burglar fiasco “Hudson Hawk” as “lukewarm”).

Here we ride along on a fascinating career that encompassed both stardom and acting as its own reward. It’s this second part of the Willis story that too often gets short shrift. Willis consistently sought out actors and filmmakers with whom he wanted to work, often knowing his name would help get a project greenlighted.

Quentin Tarantino was not yet really Quentin Tarantino when Willis signed on for what would be a secondary role in 1994’s “Pulp Fiction” (Willis wanted to play Vincent Vega, the part John Travolta landed, but he was happy to play Butch, the boxer with a fierce attachment to an old watch). As O’Connell points out, the role is often silent and shows that Willis need not open his mouth to be a strong screen presence.

M. Night Shyamalan’s “The Sixth Sense” made Bruce Willis, left, with Haley Joel Osment, the first actor to earn more than $100 million in salary for a single film, Sean O’Connell writes.

(AFP / Getty Images)

Similarly, M. Night Shyamalan was an unknown when he cast Willis in “The Sixth Sense.” The sleeper hit became the highest-grossing movie of Willis’ career, and Willis got his piece of the action. As O’Connell writes, “Because he agreed to a compensation deal worth 17.5% of both the film’s profits and its DVD proceeds, ‘The Sixth Sense’ made Willis the first actor to earn more than $100 million in salary for a single film.”

The same year as “Pulp Fiction,” Willis played a piquant supporting role in Robert Benton’s “Nobody’s Fool,” largely because he wanted to work with Paul Newman. This is my favorite kind of Willis performance. His Carl Roebuck, the sometimes-boss of Newman’s Donald “Sully” Sullivan and owner of an upstate New York construction company, is kind of a jerk, a philandering bully and Sully’s nemesis. But Willis makes him fun, giving him a swagger that turns him into more of a likable heel than a real bad guy. He fits right into a movie full of great character turns, but, being Willis, he never really fades into the background.

“Nobody’s Fool” gets only part of a chapter here, but this too is forgivable. Leafing through this book provides a reminder of Willis’ eclecticism. Put the films mentioned above with the likes of “Looper,” “12 Monkeys,” “The Fifth Element,” “Death Becomes Her,” “Moonrise Kingdom” and others, and you have a big career that often zigged when you expected it to zag.

The movies mentioned only in passing, in an appendix, are also worth noting, but not for happy reasons. Willis’ final pictures have been trickling out over the last couple of years; most of them are bad, and some demonstrate signs of his cognitive decline. “Detective Knight: Independence.” “White Elephant.” “Paradise City.” And, unfortunately, much more. This is not the way to remember such a unique actor and star, and O’Connell wisely buries these titles in the back of the book, where they should remain.

Thankfully, Willis has given us enough joy over the years to tide us over. As a wise man once said, yippee-ki-yay.