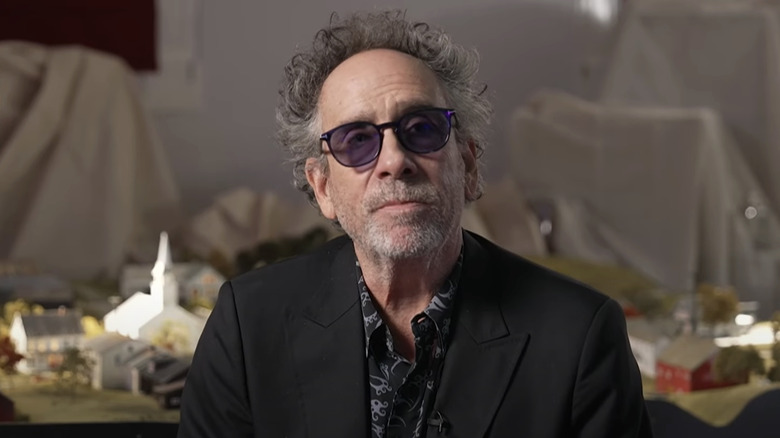

The prevailing wisdom on Tim Burton is that the filmmaker lost his touch somewhere between 1996’s “Mars Attacks!” and 2003’s “Big Fish.” Especially in the post “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” years, when he really embraced CGI, the general consensus is that Burton became somewhat of a parody of himself. But with “Beetlejuice Beetlejuice” it seems the filmmaker has gotten his mojo back, reviving his love of practical effects and the subversive element of his earlier films to deliver a movie that proves the now 66-year-old has still got it.

For me, Burton will forever be one of, if not my favorite filmmaker, simply because his earlier movies set my young imagination alight in a way no other film, TV Show, or any media has. Specifically, his 1992 “Batman” sequel “Batman Returns” remains my most transporting movie experience. The world created by Burton and production designer Bo Welch felt so immersive and became so formative for my sense of aesthetics that if you cracked open my brain you’d probably find it festooned with the gothic, art deco, fascist architecture of their Gotham.

In later years, I came to not only love but respect “Batman Returns” and Burton for the way in which he tricked my young mind into imbibing an unfiltered artistic vision by way of a Batman movie. Warner Bros, famously gave Burton free rein over “Returns,” allowing him to craft his intoxicating vision unimpeded and upsetting McDonalds in the process. For those kids like me, however, who were mesmerized by the result, Burton had instantly established himself as a formative force in our lives. Despite his late-career missteps, he remains as such for so many.

But what about the man himself? Who is Tim Burton’s Tim Burton? Well, the filmmaker previously unveiled his definitive top five movies so that we can gain an insight into the films that similarly transfixed the young Burton — and all of them were made in the 1970s.

Burton’s style was inspired as much by movies as it was his upbringing

Tim Burton was born in Burbank in 1958 and famously grew up as a loner amid his middle-class suburban environment. This same juxtaposition became a trademark of his style, most notably with “Edward Scissorhands,” which contrasts the titular outcast’s dark and gothic style with the unsettlingly pristine, cookie-cutter facades of suburban America. It’s almost the exact same energy conjured when you consider Burton, master of a certain macabre funhouse style, as having literally grown up on Evergreen Street in Burbank.

It’s a time the director recalled on a revisit to his hometown in 2006, when he was accompanied by an LA Times reporter, who he told “I still get the creeps, I still get a funny feeling driving over to Burbank.” Growing up in the valley just didn’t suit Burton, but considering how much his upbringing informed his unmistakable style, it doesn’t seem quite right to say that he was born in the wrong place.

It wasn’t just his early surroundings that fostered such a unique filmmaking aesthetic, though. Movies were a big part of his youth, and as he told the Times, “There were five or six great movie theaters, including a couple of drive-ins on Burbank, all gone.” His favorite of these was The Cornell, also since shuttered, at which he recalled seeing triple features such as “Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde,” a “Godzilla” movie, and “Scream, Blacula Scream.”

None of these ’70s b-movies, however, made their way into Burton’s top five, which he revealed to Rotten Tomatoes in 2010.

Tim Burton enjoys mistakes and ‘rough edges’ in films

Having been born in 1958, Burton was coming of age during the 1970s — a decade during which he discovered the films that would most significantly shape his artistic sensibility. As the director told RT:

“These kinds of films […] They’ve got kind of rough edges around them. There’s something primal about them. A lot of these movies, for me, some of their flaws are actually their strengths. These are the kinds of films that if they’re on, I’ll watch them. Call it masochism, I don’t know. They’re a part of me.”

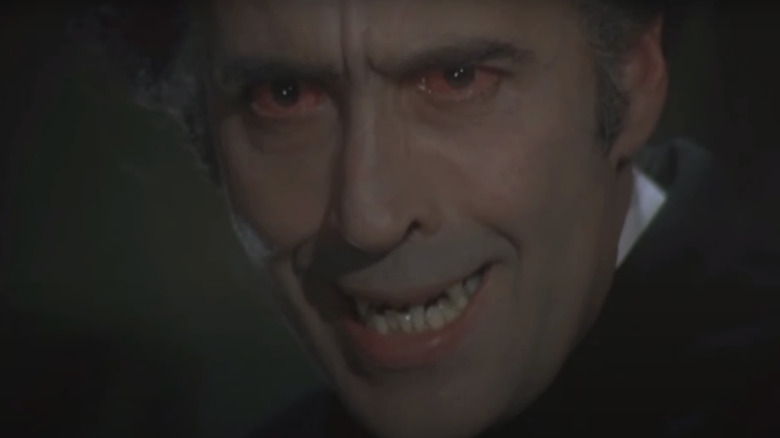

So, what exactly makes the cut? First up is the 1972 Hammer Horror flick “Dracula A.D. 1972,” which starred Christopher Lee — arguably the king of Dracula movies — as the titular vamp who’s brought back to life in 70s London. The movie was an attempt to update the character for modern audiences and possesses a distinct schlockiness as a result. But it’s this which Burton seemed to find so intriguing, telling RT, “I think it was Hammer on the decline and they thought, ‘Hey, let’s get hip,’ which was a mistake. But I enjoy mistakes sometimes.”

Next is 1973’s “The Wicker Man,” which also featured Christopher Lee in one of his post-Dracula roles. According to Burton, Robin Hardy’s film reminded him of “growing up in Burbank.” Anyone who lives in Los Angeles might wonder how the relatively sterile environs of the valley might recall the creeping terror of this British folk horror classic, but according to the director, it has to do with how “things are quite normal on the surface but underneath they’re not quite what they seem.”

The origins of Burton’s style are in his favorite films

One of the great things about “Beetlejuice Beetlejuice” is that it uses practical effects — an element of Tim Burton’s filmmaking that was so central to his style in the early years but which has been conspicuously absent from his more recent projects. It seems part of his love for a more handmade approach comes from 1973’s “The Golden Voyage of Sinbad,” which was notable for its stop-motion effects by Ray Harryhausen. Directed by Gordon Hessler, the movie saw the titular captain (John Phillip Law) set off in search of the Fountain of Destiny. For Burton, the resulting adventure contained the seeds of his own love for handmade effects, with the filmmaker saying:

“It really tapped in to what I like about movies, I mean, the fantasy but also that handmade element, when you can see the movement of the characters — it’s like Frankenstein or Pinocchio, taking an inanimate object and having it come to life.”

The combination of stop motion and giving life to inanimate objects can be seen throughout Burton’s filmography, perhaps most obviously in 2005’s “Corpse Bride,” which he co-directed with Mike Johnson. More interesting still, it seems that Burton’s obvious affinity for sympathizing with the more grotesque characters in a story comes not just from his own alienated youth, but from movies such as 1970’s “The War of the Gargantuas,” which the filmmaker described as having a “human kind of quality.” He added, “Monsters were always the most soulful characters. I don’t know if it’s because the actors were so bad, but the monsters were always the emotional focal point.”

It’s not hard to see how Burton took this theme to heart and reproduced it in his own films, but what about the whimsical element of the director’s style? The kind of funhouse sensibility that was on full display in “Beetlejuice” and “Beetlejuice 2,” with its wild and wacky creatures, is a signature of Burton’s films, and it seems part of it comes from the 1970 post-apocalyptic adventure “The Omega Man.” In particular, Burton was taken by Charlton Heston “reciting lines from Woodstock and wearing jumpsuits that look like he’s out of Gilligan’s Island.” The director admitted to being “kind of obsessed” by Heston’s performance in the film, and dubbed him “the greatest bad actor of all time.”