SHUO says he’s one of only two people in all of China making this kind of stencil art. “First, [people] just don’t have the awareness. Second, they don’t know what this is”

This piece originally appeared on the China digital media platform Radii, and this edited version is republished here with permission.

It’s the kind of balmy Sunday afternoon that makes you want a cold drink, and the Chinese street artist known as SHUO is taking me on a stroll through the hutongs after showing off one of his pieces.

“Did you see that?” he suddenly asks on our way to get milkshakes. A grin breaks out over his face. He says that I just missed an old lady on the street wearing an awesome shirt that said something about explosions. He’s very excited about the old lady’s awesome shirt and suggests that I write about awesome stuff like that. He doesn’t seem to be joking.

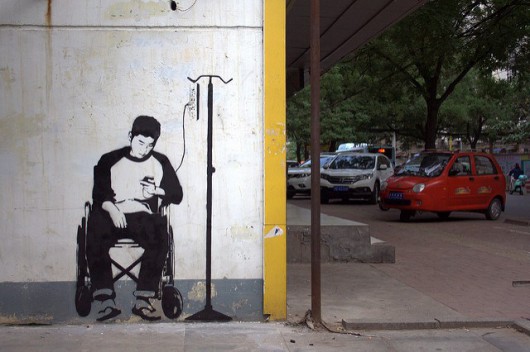

SHUO’s childlike excitement catches me off guard, if only because I expect him to be a little more cynical. The twenty-something 3D animator from Henan leads a quiet double life as an underground street artist in Beijing. He started off doing graffiti but moved onto stencil work — “I thought that stencil could express some things more easily, more concretely” — though he’s been playing around with cheaper and faster alternatives, like pasting stickers. His pieces are often deeply ironic takes on Chinese society, like this wheelchair-bound boy with his phone and charger stylized as an IV drip –

– or the URL http://www.china.com/ juxtaposed with a virus alert on a wall about to be knocked down:

SHUO is wearing white Converse sneakers, dark wash jeans, and a short-sleeved black t-shirt that doesn’t cover his tattoos. A pair of headphones is casually slung around his neck. One of his sleeves is streaked with dirt, as if he’d been scaling rooftops to put up his work — which is exactly what he did for the piece he just led me to see:

The weather-beaten blotch of paper above this Huguosi Xiaochi snack shop is one of his few extant pieces, too high up for sanitation workers to reach. It’s barely legible, a stencil of a pixelated Microsoft Word icon labeled “个人简历” (“Personal Resume”). Last year, SHUO put up several of these around Beijing in a parody of the job application process, as if to comment on how hard it is for young Chinese like him to find employment.

Even the t-shirt SHUO’s wearing — self-designed, I learn — can be construed as a knowing jab at the new normal of air pollution. It’s embellished with a blown-up version of the green shield sticker found on the 3M face-masks commonly worn around Beijing.

The 3M motif appears elsewhere in his work, as in one piece where he superimposes a mask over a child’s face in a poster of an urban paradise with blue skies and green spaces:

In SHUO’s mind, it seemed to me at first, everything is ripe for this brand of dark humor.

I was surprised to learn that this isn’t quite the case.

“I don’t care about the law, I don’t care about other things, but my starting point is fun”

One is tempted to label SHUO the “Chinese Banksy.” Like the famous UK street artist, SHUO makes provocative stencil art behind a cloak of anonymity. But while Banksy’s choice to remain unidentified might have started out as a way to avoid prosecution, it now constitutes an important part of his identity; it’s both the mystique that makes his brand so appealing and a means of control over his public image.

For SHUO, anonymity is less of a choice: his work goes mostly unnoticed.

“Making these street art pieces, I’ve never been caught or chased, no one really cares about me. Even when doing it during the day, I don’t think it matters,” he says. (This isn’t completely true; he puts up a piece of work only if the coast is clear, as it were.) The fact that his work is always taken down or painted over doesn’t help, but he’s reluctantly accepted that his individual pieces are destined to be short-lived.

“Sitting on the street is boring,” he says. He wants more things — like his art, like that woman wearing that awesome shirt about explosions — to be fun.

SHUO’s “Personal Resume” on the wall of a Beijing subway station, before and after

The New Yorker referred to Bansky in a 2007 profile as “a sort of painterly Publius” who “surfaces from time to time to prod the popular conscience,” but SHUO couldn’t even prod the popular conscience if he wanted to. His art lingers in obscurity, both offline and online. “No one really pays attention to me. One friend of mine thinks it’s really weird, that in 2014, at my peak, I never took off, and after that the response just kept mellowing.”

Why is that? “I think it’s maybe that there are relatively few people doing [street art].” SHUO says he’s one of only two people in all of China making this kind of stencil art, as opposed to spray-paint graffiti, which is far more common. (The other artist, he says, is ROBBBB.) “First, [people] just don’t have the awareness. Second, they don’t know what this [kind of art] is. If they don’t know what something is, it’s really easy for them to ignore.”

“If the government says it’s reactionary, then it’s reactionary”

Offline, SHUO prefers to remain anonymous out of a sense of self-preservation. When he was in middle school, he went online and posted a question about rumors of Xinjiang people stabbing people on the street with needles to spread HIV. The next day, two police officers came to his house and told him he’d broken the law. They let him off because of his age, but the incident left a deep impression on him.

SHUO won’t post certain pieces for fear that the police will trace them to his home, as social media platforms like Weibo require real-name verification. Besides his graffiti friends, none of his acquaintances or family know him as a street artist. He doesn’t even sign his work, and says he doesn’t want it to attract too much attention. “Because I’m acting on my own, if I suffer one blow, I might just, disappear…” He trails off.

Perhaps the most important difference between an artist like Banksy and SHUO is what animates their work. A self-described “art terrorist,” Banksy creates tongue-in-cheek pieces that reek of anti-establishment sarcasm, such as his dystopian theme park Dismaland, a blockbuster critique of the Disney franchise. Banksy told The New Yorker in the 2007 profile, “I originally set out to try and save the world, but now I’m not sure I like it enough.” In his art, the world is a big, bad joke, and although he might have run out of charity for it, he never tires of pointing out the punchline.

SHUO’s work can be much more ambiguous. He once put up a Wi-Fi sign outside of a police office — complete with the official logo — because every time he passed it, the officers inside were playing with their phones:

“It has the feeling of human warmth,” he says about the piece. “If you play with your phone, okay, I’ll give you Wi-Fi. It’s not that I’m criticizing you, not that I’m mocking you; it’s to make you feel more comfortable, I guess.”

His explanation triggers a kind of gestalt shift in how I view that work. Far from merely making fun of the police, he’s employing them in his little joke, and then sharing it with them.

If Banksy-style sarcasm feels kitsch nowadays, it’s because it has become formulaic, and there isn’t much surprise to be found in reiterating the absurd. As hard as it might be to believe SHUO when he says his motives are innocent, his art is eye-opening in its capacity for both ridicule and earnestness, in its ability to appear sarcastic and yet still double back on itself to avoid descending into cynicism.

It is also completely his own. As he said in an interview with Beijing-based website Loreli in December 2015: “I’ll never stop, it’s part of my life. I have this problem that every time I take a picture of what I’ve done and put it online, everyone that comments just writes: Banksy. Just the word: Banksy. And I’m like, Dude, it took me ages thinking of the idea, I’ve finally had time to go paint it, can you not appreciate it?”

SHUO’s art is eye-opening in its capacity for both ridicule and earnestness, in its ability to appear sarcastic and yet still double back on itself to avoid descending into cynicism

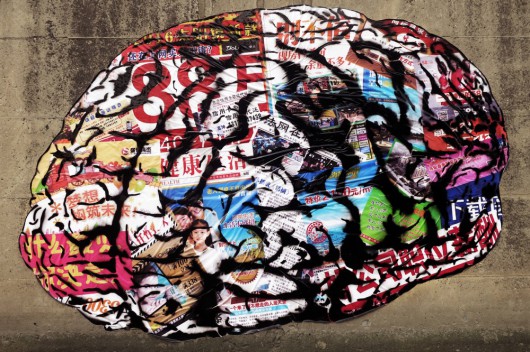

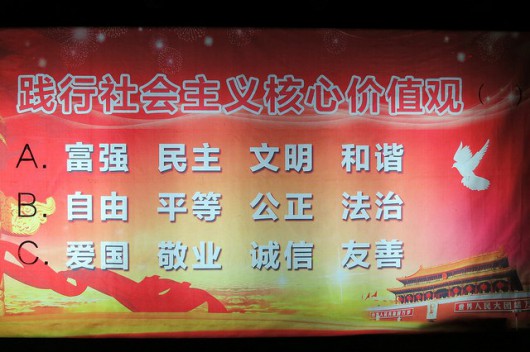

In SHUO’s worldview, dark humor can be light. One of his more sensitive pieces saw him inserting the letters A, B, and C onto a poster touting “socialist core values,” turning it into a multiple-choice question:

The piece raises questions about whether all of these values can feasibly coexist, or whether some, like democracy, are more important than others in Chinese society.

He thinks it’s harmless, though he sees the friction between different interpretations. “If you use a different logic, like in real society, some things are very harmful. Like the ABC piece, if the government says it’s reactionary, then it’s reactionary. But if I tell my other friends I’m making a joke, I think it’s pretty funny. It’s very ambiguous.”

Real society exists in tension with SHUO’s society. “I think society is a really fun game, and you can freely play this game,” he says. “But if you think according to this principle, it’s actually pretty crazy, pretty chaotic, because…” He trails off over his chocolate milkshake, collecting his thoughts. “I don’t care about the law, I don’t care about other things, but my starting point is fun. I don’t want to hurt people.”

The other day, SHUO says, he was talking with a friend about how they could make society feel more like a community. Everyone could feel like neighbors, like a big family. If he saw someone he didn’t know on the street and liked their clothes, he would feel comfortable complimenting them, without fear of misunderstanding.

I ask SHUO if he’s ever done anything like that. After all, he didn’t tell that old lady we’d seen earlier on the street that he liked her shirt.

“No,” he laughs. “I was just talking about it with my friend. We thought it would be fun if we could do that.”

It’s only a hypothetical. But his street art? It’s very real, and very fun.

This piece was published on Radii. Most of the photos above were taken with permission from SHUO’s (private) Flickr account, with some first appearing on Loreli.

Megan Pan is a writer and undergraduate at Northwestern University majoring in Philosophy and double-minoring in Poetry and Chinese.