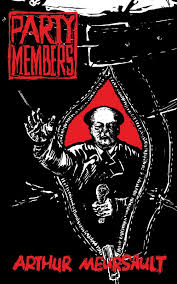

Cover art is by the renowned satirist Badiucao

If you transcribed every twisted, bitter, sick thought you ever had about China, tied it to a brick, then repeatedly smashed it into someone’s skull, you might give them an experience akin to reading Arthur Meursault’s debut novel Party Members (Camphor Press). There is no more unrelentingly savage satire of modern China ever written, and perhaps deserves more attention than it received.

The book traces the journey of Yang Wei, an unremarkable junior official (“one of a billion, not in a billion”) in a third-tier city, destined for the unheralded heights of utter mediocrity — until his penis gains consciousness, and starts telling him exactly what he needs to do to get ahead.

Less a phallic nod to Kafka than a Sino-cidal literary replay of the (largely forgotten) Richard E. Grant movie How to Get Ahead in Advertising, a satire about an ad man with a vicious boil that tell him what to do, it would be far too easy to dismiss Party Members as a crude schoolboy ode to the adage that men think with their dicks. That would miss the point.

Such is Meursault’s anger with Chinese society that he has intentionally deployed the most vulgar metaphor he can find to prod at its leaders: He thinks Party members are a bunch of dicks and says so, occasionally to devastating effect.

Not for the easily offended or those who lean toward hugging pandas, Meursault’s China flows with faeces, saliva and urine. A man gets clubbed to death by a giant penis. There is a vigorous anal rape. The lust for luxury car-ownership sees men furiously getting off in showroom Audis. Those with a taste for the grotesque will revel in any number of set pieces, many of which are masturbatory: “When they were not talking or playing with their phones, Rainy would lie next to Yang Wei, playing with his penis, letting her hands glide up and down the thick, meaty sausage like an Amazon warrior polishing her spear.”

The venomous sneering takes aim at almost every conceivable headline issue: Food scandals, greed, corruption, pollution, inequality, urban management, civic values, public defecation, GDP obsession, education, parenting, marriage, government and, of course, the Party. In lesser hands, this might be nothing more than the race-tinged rantings of a long-term expat, expanding (condensing?) his every negative thought about China into a flimsy fictional pretext. But Party Members’ dark humour, technical prowess, and outlandish exuberance save it from such a fate — though it sails dangerously close to the wind at times.

A typical members-only party

What mostly saves the book is that it is often very funny (sometimes laugh-out-loud so), not to mention savagely accurate, despite its obvious excesses. It is that rare more than half a dozen pages pass without some pithy caricature or barb, whether it’s aimed at the nation’s terrible television (“…his aging wife falling asleep in front of part 63 of a 745 episode of a Korean soap opera…”) or obsession with Japanese militarism. Often both are merged to comic effect: “Three minutes later, Yang Wei walked over from his chair, swiped the remote from her, and changed the channel back to the local TV channel’s premiere of Let’s Nuke Tokyo 3.”

China’s often ham-fisted attempts at propaganda are easily satirized, and the description of Yang Wei’s third-tier as “THE FOREST OF PROGRESS” and “THE PARIS OF ASIA” are less satire than stenography (compare the shithole concrete reality of Dongguan, a textiles hub, with its National Foreign City status). So too, the surreal effect of the cuddly, yet sinister sloganeering: “The smiley faces, dancing cats, and knock-off copies of Japanese anime characters that she normally chose to decorate the Party’s contemporary slogans gave off the air of a benevolent dictatorship controlled by a schizophrenic four year old.”

Dongguan (above) as it imagines itself

Dongguan (above) as it is

Sometimes it is difficult to tell if China’s development is more inspired by Charlie Chaplin or Joseph Stalin, a point made in the book by channeling that other totalitarian satirist, George Orwell: “It was a bright, cold day in April, and the large clock atop the Ministry building was striking thirteen. Actually, it was supposed to strike twelve, but there had been a mix-up during the clock’s manufacture and nobody could be bothered to change it.”

For all its searing rage, and certainly because of it, the book has its faults. It does not have any gears: going from neutral observation to China-is-completely-and-utterly-fucked up within a few pages, never really slowing down or changing direction. For those that like their narratives to have a natural rhythm and flow, to gently undulate with plot twists and emotional highs and lows… this is not the book. Aside from the plot-device of an unwieldy and absurdist talking penis, the novel is a bit one-track, like a hammer brutally smashing rusty nails into one’s head, page after page after page.

There’s also a sense that this merciless savagery damages the fiction itself. In the absence of any characters to care about, with Chinese cities given no color other than the bleakest grey, the effect is brutally numbing, making it easy to switch off. If the aim of satire is to affect some type of change, then Party Members misses the mark. The book’s monotonous ferocity drains the book of the emotional impact it might have delivered, enticing the reader to think China is getting exactly what it deserves — and nothing can be done about. That bleakness—nihilism, really — might be too much for some readers to bear. For others, it might be just the tonic.

The author, Carlos Ottery, is on Twitter @CharlesOutre