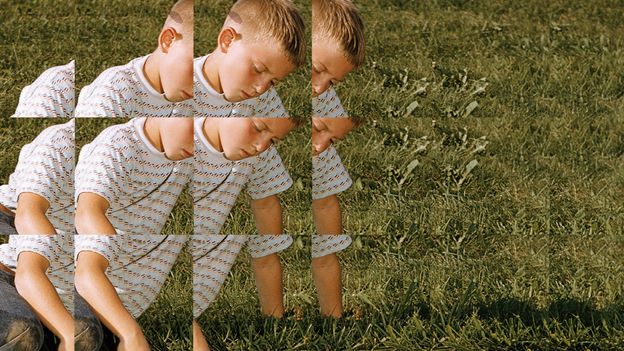

Edouard Taufenbach and Bastien Pourtout

Edouard Taufenbach and Bastien PourtoutChildren’s perception of time is relatively understudied. Learning to see time through their eyes may be fundamental to a happier human experience.

My household is absorbed in debate over when time goes the fastest or slowest.

“Slowest in the car!” yells my son.

“Never!” replies my daughter. “I’m too busy for time to go slow, but maybe on weekends when we are on the sofa watching movies.”

There’s some consensus too; they both agree that the days after Christmas and their birthdays dawdle by gloomily as it dawns on them they have to wait another 365 days to celebrate once more. Years seem to drag on endlessly at their age.

It’s a feeling I remember well; the summer holidays filled with water play, skipping on the freshly cut lawn, the laundry drying on the washing line whilst the Sun blazed. At moments like that, time really did feel like it moved slowly.

Teresa McCormack, a professor of psychology who studies cognitive development at Queen’s University Belfast in Northern Ireland, believes children and time is a hugely understudied topic. Her work has long probed whether there is something fundamentally different about time processes in children, such as an internal clock that functions at a different speed to that of adults. But there are still more questions than answers.

“It’s strange that we don’t still really know the answers to questions like when do children have a proper distinction between the past and the future, given that this seems to structure the entire way that we think about our lives as adults,” says McCormack. She explains that whilst we don’t have a clear understanding of when children grasp a sense of linear time, we do know that from relatively early on in development, children seem to be sensitive to routine events such as meal times and bed times. She stresses this is not the same as having an adult sense of linear time.

In contrast to children, adults have the capacity to think of points in time independently to when an event takes place, owing to their knowledge of the conventional clock and calendar system. Semantics also play a part. “It takes time for children to actually become completely competent users of temporal language, using terms like before, after, tomorrow and yesterday,” says McCormack. (Read about how our language affects our sense of time and space.)

McCormack adds that our understanding of passages of time are also based on when people are asked to make those time judgements. “Are you asking the question while events are happening or retrospectively?” She gives an example that many will relate to. “The time from when my child was born to when they left home now seems as if it went in the blink of an eye. But during the time when you’re actually engaged in the business of child rearing, a single day lasts an eternity.”

Edouard Taufenbach and Bastien Pourtout

Edouard Taufenbach and Bastien PourtoutStudies have found that judging the duration and the speed of a passage of time develop separately in humans. Younger children below the age of six seem able to grasp how quickly a lesson passes in a classroom, for example, but their judgement is linked more to their emotional state than the actual duration. These two elements come together at a later stage when children understand the link between speed and duration.

Much research focuses on how our experience of the passage of time depends on how our brain stores memories and captures experiences. This is something that has long fascinated Zoltán Nádasdy, associate professor of psychology at the Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest.

As an undergraduate student at the University of Budapest in 1987, Nádasdy convinced his fellow students to undertake a field study on time perception amongst children and adults. He wanted to understand why time appears to dilate when there’s an accident, for example. The experiment was simple. They showed groups of children and adults two videos, both one minute long and asked them which video felt the longest and which felt the shortest.

Fast forward over three decades, and Nádasdy and his team decided to repeat the experiment. An action-packed cops-and-robbers clip and a comparatively uneventful video of people rowing on a river were shown to three age groups before they were asked to rate the duration using hand gestures. The outcome was the same. “The four- to five-year-olds found the action-packed video longer and the boring one shorter. For the majority of grown-ups it was the opposite.”

They used hand gestures to understand if participants perceived time as a horizontal flow, something that was evident in all three age groups.

What the experiment shows, says Nádasdy, is that in the absence of a sensory organ to predict time, humans use other approximations.

“Our explicit sensory experience of the time is always indirect, which means that we need to reach for something that we think correlates with time,” he says. “And in psychology this is called heuristics. So, for kids what can they reach out to? How much they can talk about it.”

That proxy tends to change once children go to school, a place where they begin to learn about the concepts of simultaneity and absolute time. “It doesn’t give us the sensation of time, but it just replaces those heuristics with another one. When you go to school you are on a schedule. Your day is totally controlled.”

McCormack raises two additional factors at play when it comes to children’s concept of time. “One is that their control processes are not the same as adults,” she says. “They can be more impatient and find it more difficult to wait,” she says. “It can also be related to their attentional processes as well. The more attention that you pay to a period of time passing, the slower it seems to go for you.”

Research by Sylvie Droit-Volet, professor of psychology at the Université Clermont Auvergne in France, and John Wearden, emeritus professor of psychology at the University of Keele in the UK, found that the same applies in adults. They discovered that a person’s experience of time passages in daily life does not fluctuate with age, but with their emotional state. Put simply – if you are happier, time passes faster. If you are sad, time drags.

A key example of this was seen during lockdown, when researchers found a slowing of the passage of time associated with being more stressed, having fewer things to do and being older.

There’s also a degree of physical deterioration as we age that might also affect our judgement of time, according to Adrian Bejan, a professor of mechanical engineering at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. He has tried to explain the puzzle of our perception of time through the lens of a theory he developed in 1996 on the “physics of life” that has become known as “constructal law“.

“The biggest source of input to our brain is through vision, from the retina to the brain,” says Bejan. “Through the optical nerve the brain receives snapshots, like the frames of a movie. The brain develops in infancy and is used to receiving lots of these screenshots. In adulthood the body is much bigger. The travel distance between the retina and the brain has doubled in size, the pathways of transmission have become more complex with more branches. And in addition with age, we experience degradation.”

This, he says, means the rate at which we receive “mental images” from the stimuli of our sensory organs decreases with age. This creates the sensation of compressed time in our minds as we are receiving few mental images in one unit of clock time as adults compared with when we are children.

Edouard Taufenbach and Bastien Pourtout

Edouard Taufenbach and Bastien PourtoutStudies into age-related neurodegenerative changes suggest there may well be an association between optic nerve decline and a slowing in the speed at which information is processed and working memory capacity. But more work needs to be done to understand this fully.

What you are looking at can matter too. Time perception can be impacted by the properties of what is being observed – the size of the scene, how easy it is to remember and how cluttered it is. A recent by psychologists at George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia, found that the first two factors dilate time whereas clutter and how busy a scene is contracts it.

Something else happens for many of us as we get older – a less fluid and more inflexible routine kicks in. Research has found that the more time pressure, boredom and routine in a person’s life, as well as the more future-orientated an individual is in contrast to living in the moment, the faster time is experienced.

What you are doing in the present is unsurprisingly paramount to our understanding of time, no matter our age. As our mental workload increases, for example, we tend to experience a shortening of time as we underestimate the duration of a task the more demanding it is.

Take a fun-filled two-week summer camp – it may be more memorable than your entire school year. Nádasdy explains that it is highly likely that those summer camp memories would occupy a much larger piece of brain tissue, because of the sheer number of adventures that took place during that short period.

“It’s possible that people’s judgments about what actually happened during a particular time period in part reflects their memory for the amount of novel things that they remember happening,” says McCormack. “For example, if you’re an older adult, there might not have been very many big life changes that have happened for you over the last 10 years.” But when there are, those will stick in your memory just as much as that summer camp.

Bejan has some other less exertive ideas too.

“Slow it down a little more, force yourself to do new things to get away from the routine,” he says. “Treat yourself to surprises. Do unusual things. Have you heard a good joke? Tell me! Do you have a new idea? Do something. Make something. Say something.”

For more science, technology and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and X.