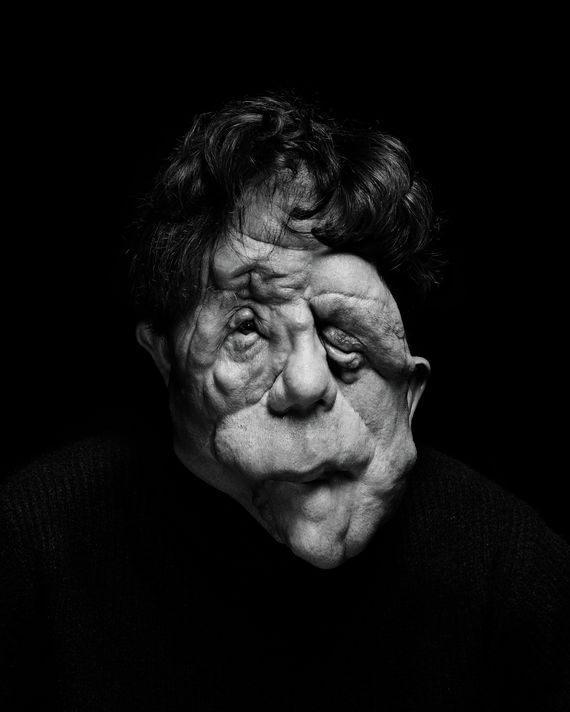

Photo: Nadav Kander for New York Magazine

Adam Pearson insists his acting career started as something of a joke. It was 2013, and he had just received an email about a casting call from Changing Faces, a U.K.-based nonprofit he had worked with that is dedicated to helping people with visible differences on the face, hands, or body. A film called Under the Skin, to be directed by Jonathan Glazer, was looking for an individual with facial disfigurement to play a part. Pearson, who has neurofibromatosis type 1, a condition that produces benign skin tumors all over his face, certainly fit the bill. But he had never acted before and had no intention of doing so. “Let’s waste someone’s time for a while,” he remembers thinking as he sent off his CV. Then he was asked to record a short video. “Next thing you know,” he says, “you’re in Glasgow with Scarlett Johansson wondering what the hell has happened.”

Quite a bit has indeed happened since then. “I came in hot and high and wildly unprepared,” Pearson says about doing Under the Skin, but his scenes in Glazer’s moody sci-fi thriller, in which Johansson’s human-harvesting alien picks him up and later sets him free, were probably the most memorable moments in one of 2013’s most acclaimed films. (Much of their dialogue, it should be noted, was improvised.) Since then, Pearson, who at the time was helping cast reality-TV shows, has hosted a number of TV specials and appeared on a variety of other programs, often as an activist for greater visibility and rights for the disabled. Now, he has what is certainly his biggest role to date as one of the stars of Aaron Schimberg’s A Different Man, a noirish, existential comedy that was one of the breakout titles at this year’s Sundance Film Festival and will be released by A24 in September, right at the start of awards season.

And it seems he’s rather nervous about it. I meet Pearson at the Ludoquist, a board-game café in Croydon, the South London town where he has lived pretty much all his life, just a few days after the trailer for A Different Man dropped online, and he’s still trying to process it all. The film was partly inspired by him — though maybe not quite in the way one might think. A Different Man follows Edward Lemuel (Sebastian Stan), a morose and introverted struggling actor with neurofibromatosis whose life changes when an experimental treatment miraculously removes the tumors covering his face. Then he meets Pearson’s Oswald, who has the same condition. Unlike the always retiring Edward, however, Oswald is a bon vivant comfortable in his own skin — a great dancer, a karaoke master, and a ladies’ man. Slowly but surely, this extroverted and exceedingly polite dynamo takes everything from the now handsome but increasingly surly and resentful Edward, including his playwright girlfriend, Ingrid (The Worst Person in the World star Renate Reinsve), and the acting role Edward feels he was born to play: an Off Broadway theater piece by Ingrid called Edward, about a man with facial disfigurement. “You think you’re watching a film about this man who gets cured and then his life’s going to be okay, and then Adam Pearson just turns up and kicks him down the stairs for the rest of the film,” Pearson says, laughing.

From left: With Scarlett Johansson in Under the Skin. Photo: A24On set with A Different Man director Aaron Schimberg. Photo: Matt Infante/A24

From top: With Scarlett Johansson in Under the Skin. Photo: A24On set with A Different Man director Aaron Schimberg. Photo: Matt Infante/A24

Schimberg conceived of A Different Man after working with Pearson on 2019’s Chained for Life, which was also critically acclaimed but received a limited release. In that, Pearson played a subdued, kindly actor performing in a schlocky thriller opposite a beautiful actress played by Jess Weixler. “I think the audience just assumed Adam was playing himself in Chained for Life,” Schimberg says. “He looks a little nervous and awkward, and people thought that’s who he was. But the character was really based more on myself.” The director wanted to write a role for Pearson that reflected the actor’s range and his effervescent charm.

That charm is on full display as Pearson and I spend a lazy afternoon playing several board games, a hobby he admits has grown into an obsession. “If you asked me to count how many board games I own, I’d probably have said 20,” he says. “It turns out I have 118!” Since I’m basically useless at most board games, Pearson cheerfully and patiently guides me through rounds of Shobu, Onitama, and Chicken vs Hotdog.

Almost everybody at this café seems to know the 39-year-old Pearson. It’s one of the reasons he hasn’t moved out of Croydon, where he still lives with his mother in the house where he grew up. Some of his childhood friends now own bars and restaurants in the area. The evening after our interview, I meet him at a local café–bar–vinyl shop called Riff Raffs, where an artist friend of his is DJ-ing. He tells me the two of them are working on an experimental-film project as well as a potential art installation. He’s also preparing a documentary, a sitcom, and a book proposal. During his downtime on Chained for Life, when he wasn’t watching pro wrestling or doing karaoke with the rest of the cast, he taught himself close-up card magic. (Amid his current whirlwind of activity, he has also been going to the gym a lot more. “I want to get fit,” he says. I note that he already seems to be in very good shape — both Under the Skin and Chained for Life feature him in nude scenes — but he says he wants to get fitter. He jokes that he aims to be one of those guys who are always talking about their workouts: “I’m going to be unbearable!”)

Fall Preview 2024

The highly anticipated movies, plays, television shows, albums, books, art shows, podcasts, and more coming this season.

Close

The highly anticipated movies, plays, television shows, albums, books, art shows, podcasts, and more coming this season.

It helps that he has basically been an extrovert all his life. He was first diagnosed with his condition at the age of 5, after receiving a bump on his head that didn’t seem to heal. (Interestingly, he has an identical twin brother, Neil, who also has neurofibromatosis — but in Neil, the condition manifests not through facial tumors but short-term-memory loss.) Next came years of doctor appointments and facial surgeries: 39 to date. “When you’re that age, you’re mildly oblivious to it,” Pearson recalls. “I was also taught from a really early age to live the life you’ve got rather than mourn the one you don’t. So I’ve always been this sort of head-down, crack-on kind of kid.”

But he wasn’t unaware that he was different, especially once he started school and became the target of a whole host of attacks from his fellow students who called him “Elephant Man” and “Scarface” and spat on him. He bristles to this day at the “playground politics” of childhood, but he admits that he often gave as good as he got. “I was always a lot smarter than the kids giving me aggro, so I came back and was good at verbally eviscerating people on the playground,” he says. “I almost became the architect of my own downfall because I became the problem. If I could go back and do it, I’d do it differently.” Pearson still runs into some of the people who gave him a hard time back in school and says their interactions are now nothing but cordial: “I think judging someone on who they were and how they behaved when they were a teenager is unfair and unreasonable.” This speaks to his belief that in order to make any real progress in the way disability is talked about and portrayed, we need to change the way we talk about sensitive topics. “A lot of campaigning now is shouting people down for saying the wrong thing rather than lovingly correcting them to say the right thing,” he says. “That whole middle ground of nuanced conversation doesn’t exist.”

Pearson knows that the more public he is, the more of a difference he can make in the way that people react to him and others like him. That’s been the thrust of much of his presenting work, in which he guides viewers through the issues surrounding disability with humor and sincerity. His first documentary appearance was in a 2005 TV special called When Your Face Doesn’t Fit as a teenager. After graduating from university, he found work at the BBC as an assistant in commissioning. It was only a six-month contract, so he made a point of asking everyone who would talk to him out for coffee as a way of building contacts. He soon found himself working in development and began researching and presenting his own shows.

Photo: Nadav Kander for New York Magazine

What Chained for Life did through its playful deconstruction of exploitation movies, A Different Man does in more structural ways. The film essentially contains a conversation about the portrayal of disability onscreen. Stan, a hunky movie star with awards and a ton of Marvel credits, appears in his early scenes in an expertly made prosthetic mask. He’s wonderful in the film and won a well-deserved Best Leading Performance award at the Berlin International Film Festival, but I would be lying if I said I didn’t feel some initial discomfort watching him play the part. That anxiety is wholly intentional. “On Chained for Life, there was some criticism that just having Adam in the movie was inherently exploitative,” Schimberg recalls. “But if you can’t cast somebody with a disfigurement, then you have to cast people in prosthetics, and that really goes against what we think of as representation. It’s damned if you do, damned if you don’t. So one of the inspirations for the movie was to have these two opposing ideas face off within the film.”

When Pearson’s Oswald shows up in A Different Man, it’s a delightful surprise not just for the characters onscreen but for the audience as well. “It’s a means to an end in a way that’s clever,” says Pearson. “We’re highlighting the fallacy of doing it by doing it. You spend the first half of the film going, Can they do that? And then Oswald walks up, and everyone suddenly goes, Oh, oh, thank God.” But Pearson also knew that Stan could connect to the material because of the unique gauntlet celebrities often have to go through. “You might not know what it’s like to live with a disfigurement,” he told Stan before production, “but you do know what it’s like to have that level of invasion whereby people think they own you because they see you in Gossip Girl or the Marvel films.”

Of course, celebrities have a lot more power than the disabled do. And having more thoughtful conversations doesn’t preclude the need sometimes to confront those who are needlessly cruel or organizations that benefit from such exploitation. The Ugly Face of Disability Hate Crime shows Pearson trying (and failing) to get a genuine response from Google, owner of YouTube, about why it’s not doing anything about a comment on a clip from Under the Skin in which one user suggests he be burned alive. Earlier this year, he found a tasteless YouTube account with the handle “MostAmazingTop10” that was using images of his face to promote a video about “the Top 10 Deadliest Substances on Earth Too Scay [sic] to Touch.” He reached out to the company, asking the video be removed and that he be issued a public apology. He was told that only a private apology would be given. “We had this really weird back-and-forth, and he just refused to take accountability,” he says of his exchanges with the head of the company. “My family saw that. My friends saw that. I heard about it from, like, eight different people. You have a YouTube channel with 7 million-plus subscribers. That’s a responsibility.” In his regular Instagram videos, Pearson playfully calls out people who have posted mean comments about his appearance. “I only call out the bad guys for a bit of a laugh,” he says, though he adds that he has now reserved the Instagram handle @fthatguy in case he ever “wants to go full nuclear.” Still, he doesn’t know if he’ll keep it up. Dealing with so much negativity can be exhausting.

Also, he may not have the time. Pearson has enjoyed his experiences at the world’s big film festivals. He fondly remembers a woman at Sundance who had a matching outfit and sunglasses with her Chihuahua. He appreciated being able to take his mom and brother to his Berlin premiere in a limo and watch them watch him step out into the flash of cameras and sign autographs. “For years, my mom said, ‘I’m sorry, I just don’t believe you’re famous,’” he says. “And then she realizes that I am actually. She’s there on the red carpet pissing herself laughing.”

See All