Recently after a literary event, I was hanging out with some other writers and a conversation about older books led to a parlor game. One of us would read the titles of bestselling novels from a few decades ago and everyone else would try to guess the authors’ names. It was hard. Even with hints. We switched to National Book Award finalists, thinking we’d be more likely to remember acclaimed books than merely popular ones. We did marginally better. A couple titles were easy—your Pale Fires and The Haunting of Hill Houses—but most were not remembered. What was more surprising than the fact we couldn’t match names to (once) famous books was that many of the authors themselves were completely obscure, especially to the younger people present. We were writers and professors. If we didn’t remember these authors, who did? The conversation moved on but I think everyone came away with a reminder: literary fame is fickle and fleeting.

(Here, try it yourself. I’ll list the 6 National Book Award finalists for 1967 followed by the top 6 bestsellers of that year. NBA: The Fixer, The Embezzler, All in the Family, The Last Gentleman, A Dream of Kings, Office Politics. Bestsellers: The Arrangement, The Confessions of Nat Turner, The Chosen, Topaz, Christy, The Eighth Day. Many readers will probably know the authors of Nat Turner and perhaps The Fixer, but the others?)

I remembered this as I watched the debates about whether or not popular recent novels like Harry Potter and The Hunger Games will be read “in 100 years.” I don’t really care much about either series, but I am always a little surprised at how confident many are that what is popular now must necessarily be popular in the future. This is rarely the case. Few things endure at all, after all. And 100 years is quite a long time. 1924 is an almost unrecognizable world. The differences in technology, global politics, and culture are hard to grasp. This is a time period when vaudeville was still one of the most popular artforms and feature films barely even a thing. Those 100 years have seen the rise and fall of empires and much of culture move to entirely different technologies (video games, television, the internet, etc.) What will the world even look like in 100 years?

I’ll save the speculation for a science fiction novel I suppose. But even limiting ourselves to literature, it’s simply the case that what endures has minimal correlation to either contemporaneous popularity or contemporaneous acclaim. Acclaim has a bit better track record—the names of early Pulitzer Prize winners are more familiar than the names of bestselling novels of the 1920s for example—but neither is a guarantee of anything. Here’s the bestseller list of 1924, which includes titles so obscure they have red-ink dead links because no one has bothered to even make a perfunctory Wikipedia page for them:

A good example of a famous name few recognize today is Winston Churchill. No, not the British one. I’m talking about the wildly popular American author of such (once) classics as Mr. Keegan’s Elopement and Mr. Crewe’s Career. Such books made him so well known that the British Winston Churchill had to write under the penname Winston Spencer Churchill (or Winston S. Churchill) to avoid confusion. Today? The novel that made Churchill a household name has less than 100 ratings on Goodreads.

But it isn’t just some popular works that disappear. It is even the most popular ones. The Harry Potters and MCU films of yesteryear. Take Zane Grey, who was the most popular author of the most popular genre (Westerns) in his day. Grey was one of the first millionaire authors ever and his novels were adapted into over 100 films. He was so popular and prolific that even though he died in 1939 his publisher had a stockpile of manuscripts they published yearly until 1963! Almost no one reads him today.

Writing For, Within, and Against the Market

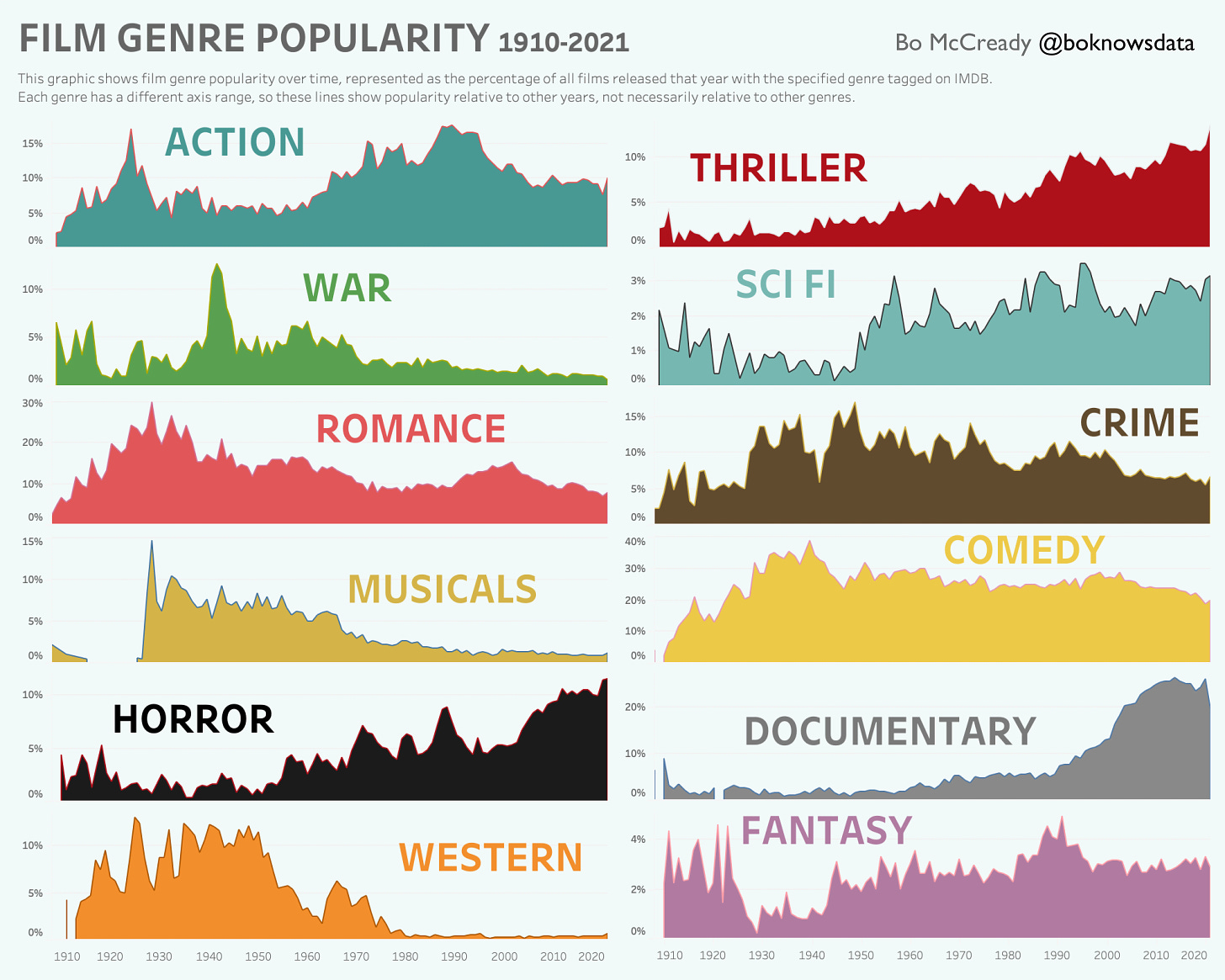

Grey’s slip to obscurity points to one of the whims of literary fortune: genres rise and fall. Last month, I talked about how quickly the market moves in the near term—how writing toward the market often means your writing for a market that will have moved on by the time your book comes out—and this is far more pronounced in the long run. The Western was once a dominant genre in American film, TV, and literature. Today? Not so much. There is the occasional work of course, but the Westerns prominence has been replaced by genres like superhero films and YA SFF. In 100 years, those genres may feel just as antiquated.

(In the above, the few categories that maintain popularity are impossibly broad ones like “comedy.” Within them, styles and subgenres rise and fall as much as musicals and westerns I’m sure. Similarly, the kind of fantasy films popular today are very different than the ones in the 1920s.)

I could go on and on with examples of how art fades. Perhaps the most interesting question is what makes something endure. What makes a work speak through time to multiple eras and contexts? There are certainly works from 1924—100 years ago—that are read today: A Hunger Artist by Franz Kafka, Billy Budd by Herman Melville, We by Yevgeny Zamyatin, The Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann, Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair by Pablo Neruda, multiple books by Agatha Christie, etc. I would like to think that quality helps determine what lasts yet it is obviously more than that. Melville and Kafka, for example, both went through long periods of obscurity before being “rediscovered” decades after their deaths. They are two of my favorite writers, but I have to sadly admit it is possible they will lapse into obscurity again in the future (and perhaps be rediscovered yet again and then forgotten again and so on).

To offer a theory though, I think what lasts is almost always what has a dedicated following among one or more of the following: artists, geeks, academics, critics, and editors. “Gatekeepers” of various types, if you like. Artists play the most important role in what art endures because artists are the ones making new art. Indirectly, they popularize styles and genres and make new fans seek out older influences. Directly, artists tend to tout their influences and encourage their fans to explore them. In literature that takes the form of essays, introductions to reissues, and so forth. In music, it might be something like cover albums as in the way Nirvana’s Unplugged introduced a new generation to older bands and musicians. Academics is pretty obvious. The older books with the best sales are mostly ones that appear on syllabi. And geeks and critics are the ones who extensively explore a genre or category’s history and proselytize their favorites. Editors are the ones who actually chose the older books to republish and can champion obscure books back into the public eye.

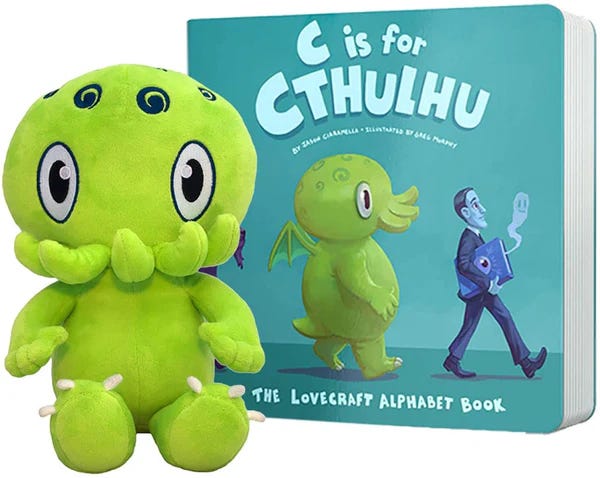

As a specific example, take H.P. Lovecraft. He died obscure and impoverished yet is easily one of the most influential horror authors today for better or worse. He’s so popular he’s become something he’d find horrifying: a name attached to “Cute-thulu” merchandise including whimsical stuffed toys. How did that happen? It isn’t because casual readers randomly found his books or that mass culture chose to elevate him. It is because later horror authors, including famous ones like Stephen King, sung his praises: “Lovecraft … opened the way for me, as he had done for others before me.” As did authors who simultaneously critiqued his racism and homaged him, like Victor LaValle in The Ballad of Black Tom. And because horror geeks—the kind who read far more books than average people—touted his importance and kept his works read.

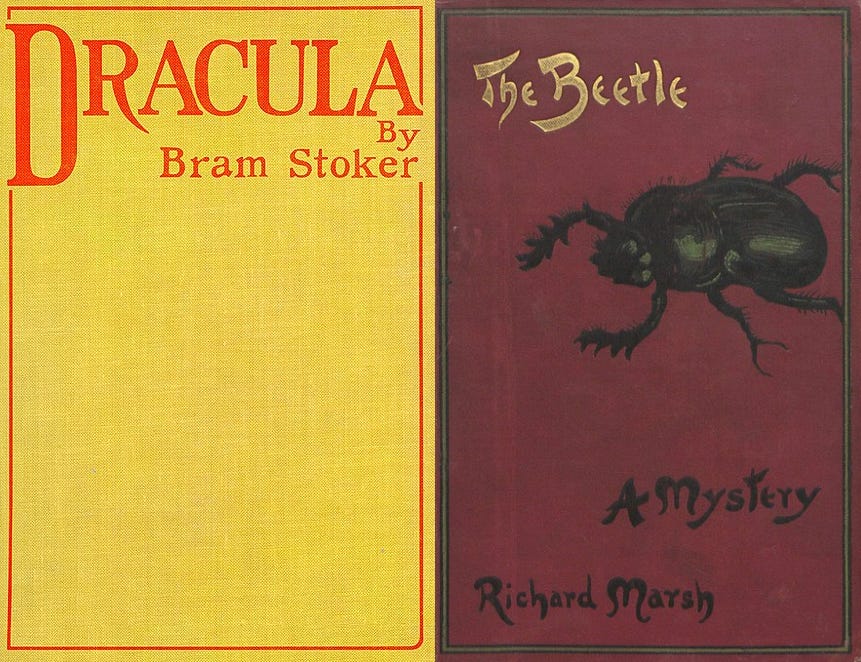

Many of the books that endure are, like Lovecraft and cosmic horror, foundational texts in a style or genre. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein as the first science fiction novel and archetypal mad scientist narrative. Bram Stoker’s Dracula as the template of vampire fiction. Etc. It helps those books are very good, of course. But once again it’s impossible to know what will be foundational in a style or genre because that is dependent on what comes later. Dracula is a good example, because it was published the same year—and sold fewer copies than—another Gothic horror novel: Richard Marsh’s The Beetle. The Beetle features a monster related to Egyptian mythology at a time when British interest in Egypt was at its height (in a Orientalist way of course). Why did vampires and a Romanian setting (e.g., Netflix’s Castlevania series) become huge in English-language horror while ancient Egypt horror took a backseat? It’s certainly not because British and American writers deemed the latter Orientalist and offensive—we still get movies like The Mummy now and then. I think it’s pretty much because generations of horror authors, movie directors, video game makers, and so on just made a lot of cool and popular vampire stuff. The endurance of Dracula is part Bram Stoker, but mostly Bela Lugosi, ‘Salem’s Lot, Buffy, Castlevania video games, and so on.

Still, if you want to predict what will last I think you should look to what has partisans among dedicated readers—scholars, critics, genre nerds, etc.—rather than what merely sells well with casual readers. Specialists not popularists. And then what work seems influential among younger artists, such as work that seems foundational in a certain style or subgenre. That’s might get you in the ballpark, even if you will strike out more with most swings.

Another way for a work to endure is through the randomness of popularity in another medium. Many books last simply because a film or TV adaptation is popular, although often the books are simply eclipsed. Many younger people probably don’t even realize that Jaws and The Godfather were originally popular novels. (Film/TV can also popularize things in amusingly random ways. Recently, an anime show with characters named after older Japanese writers led to a surprising revival in the sales of Osamu Dazai’s novels…. merely because he shares a name with a character.)

Lastly, I do have to acknowledge that we currently live in the “franchise era” in which the biggest works are not actually individual works by individual artists, but sprawling multimedia empires with video games, movies, TV shows, action figures, and even amusement parks attached. Perhaps this means that the rare super franchises—your James Bonds and Harry Potters and Star Warses—can never die. I’m not entirely convinced. Even this shall likely pass. Time is fleeting. The brief candles flicker, even for sprawling multibillion corporate franchises. All we can do is write what we like and read what we love, and hope others like it too either now or in the future.

If you like this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my recent science fiction novel The Body Scout that The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent.”

Other works I’ve written or co-edited include Upright Beasts (my story collection), Tiny Nightmares (an anthology of horror fiction), and Tiny Crimes (an anthology of crime fiction).