When Moon Zappa and I arrange a place to meet to discuss her memoir, Earth to Moon, she requests the San Fernando Valley, which I wasn’t expecting. This is the area of Los Angeles that Moon immortalized in “Valley Girl,” the Grammy-nominated 1982 pop song she created with her father, revered musician Frank Zappa, at age 14. With that song, Moon sparked a cultural movement, the “Valspeak” lexicon, and the impetus for Valley Girl the movie.

The creation of “Valley Girl” and the avalanche the song brought, which Moon dealt with on her own, would fit well with child star stories. You can see for yourself in a YouTube wormhole of “Valley Girl” interviews, including an offensive one with Howard Stern when Moon was 25, which to quote her is, “Hard to watch, right? I would love to sit down with Howard Stern and go over that interview with him.”

More from Spin:

- Choppered and Tuned

- Frank Zappa’s Funky Nothingness Is Full of Meandering, Revelatory Jams

- The 50 Best Albums of 1972

My introduction to the Zappa family happened when Moon and her younger brother Dweezil were VJs on MTV in 1986. They were unlike the other VJs who took themselves way too seriously. These teenagers looked like they were having a blast, with a tongue-in-cheek attitude that poked fun at everything. I had no idea who Frank Zappa was, but I was jealous of Moon’s and Dweezil’s cool jobs. “I was hyper-jealous of people that grew up with families where they had regular meals and wore loafers with no socks,” Moon retorts.

We’re meeting at the Moon Café—my choice—and when Moon first arrived, she was momentarily dazed. “On the sidewalk there’s an image that says, ‘Not all cults are bad,’” she says. “I had to laugh, because in some ways, I was attempting to escape the cult of fame and my family.”

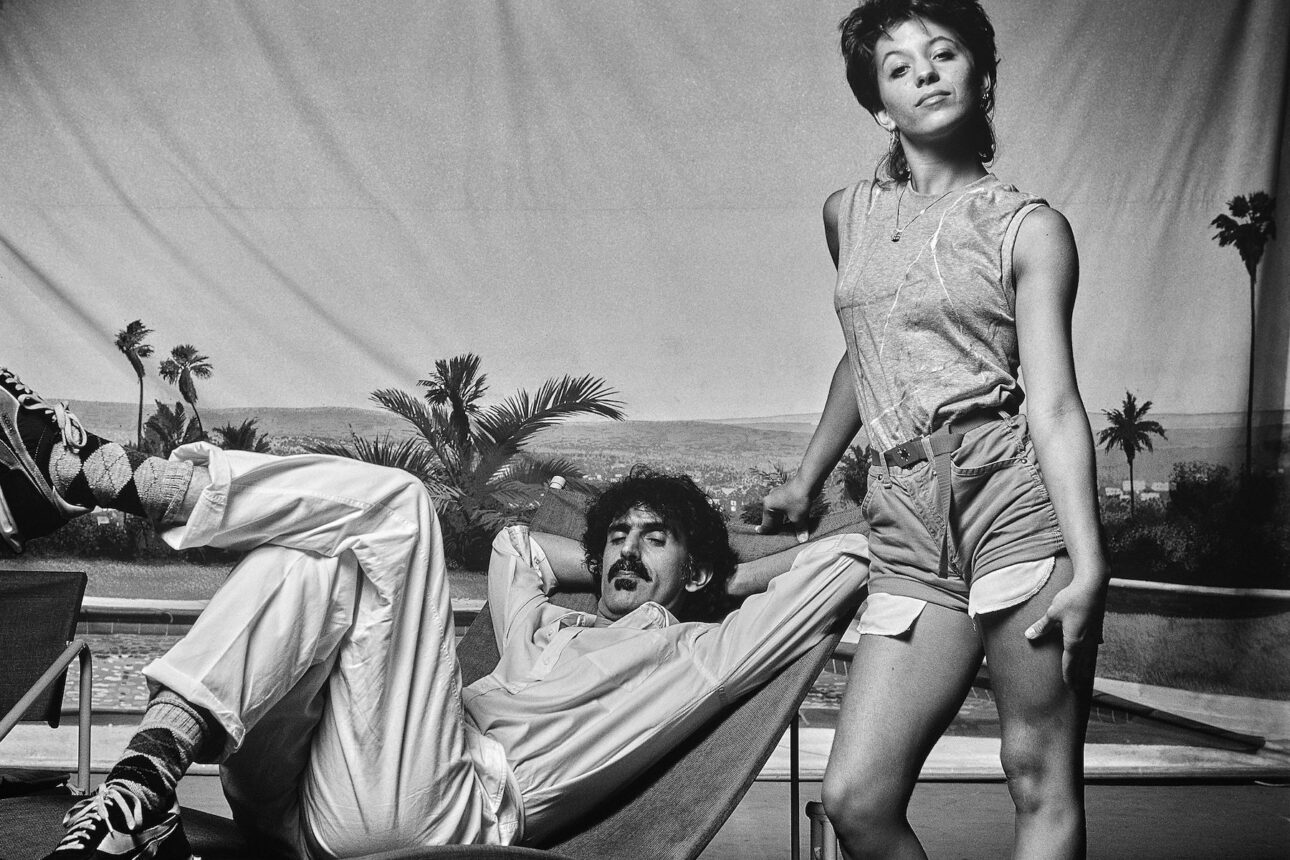

The blessing and burden of the Zappa name are inescapable for Moon. Stories of life in the unconventional Zappa household are legendary. Filmmaker Alex Winter painted a well-rounded picture of Frank Zappa in his documentary, Zappa, which made a fan out of me. But after reading Earth to Moon, I have to reexamine my feelings about the man.

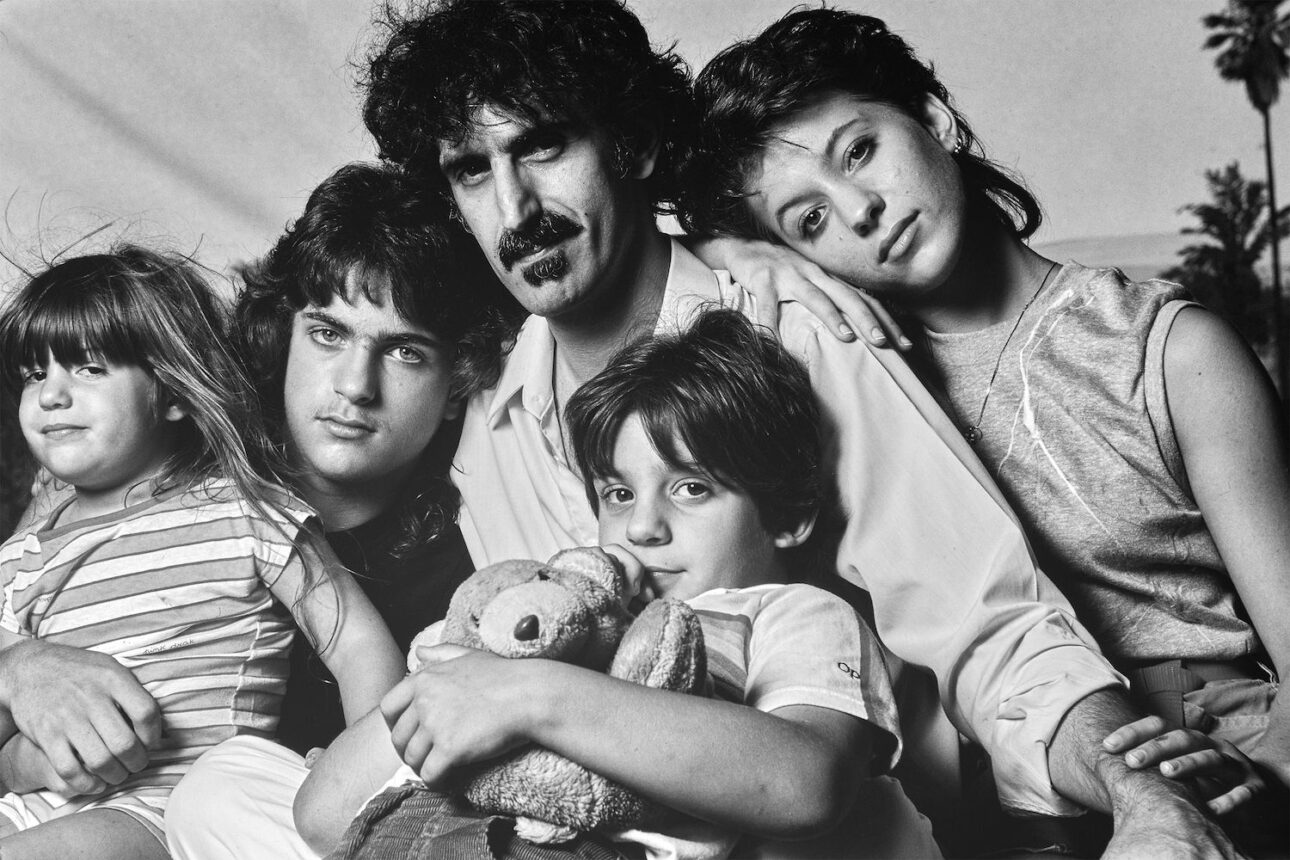

Earth to Moon is Moon’s story. There is a young tone to the memoir that feels like she is shielding herself from the reality of her life growing up. In addition to Frank, her almost equally well-known mother, Gail, and her siblings (Dweezil, Ahmet, and Diva) are inextricably involved. But this is Moon’s truth, laid bare, and it’s not pretty. Frank’s artistic impression is an undeniable part of music history’s colorful fabric. But when his actions are seen through his first-born’s eyes, they take on a different slant, one that forsakes the family for the art.

It’s entertaining, if heartbreaking, to read about Moon going to school with Janet Jackson and Justine Bateman, getting set up with Woody Harrelson, and their brief and sad relationship. It’s bizarre to think of her driving to a party to declare her love to Jon Bon Jovi, and having Tom Cruise escort her into a movie premiere so her date, Emilio Estevez, doesn’t get busted by his girlfriend. She gets yelled at by k.d. lang after interviewing her for VH1, and although she’s still not sure why, that interaction resulted in Moon making major positive changes in her life. “It was an incredible act of generosity to scold me, and school me,” says Moon. “I’ve had a few slaps like that I have so much gratitude for.”

Yet Earth to Moon is not a celebrity-dish memoir. At its core, it is about Moon’s experiences with Gail and their negative ripple effect—later in sharp contrast with Moon’s experiences as a mother herself. Upon Gail’s death in 2015 (Frank died in 1993), Moon and Dweezil were left with a lesser share of Frank’s legacy and no decision-making power about anything Zappa-related. This caused a rift between Moon and her siblings that continues, and a questioning about her relationship with her family that is painful to read and to talk about, at least for me. But Moon has a lot to offer, and she does so with an open heart.

“I still have so much love for my family,” she says. “My father was my ally in the family and the first love of my life. Even though I didn’t necessarily agree with his choices, he was a ‘take me as I am’ person. As a dad, I never felt I was in good hands. But artistically, I felt the world was in excellent hands. It was so strange to reconcile that paradox.”

With Earth to Moon, she is not throwing herself a pity party. If anything, Moon is giving of herself. You can hear her crying in the audiobook, and tears come to her eyes, and mine, at regular intervals during our conversation. When that happens, I concentrate on her feather earrings that are as long as her double-braided hair, or on the horizontal shading of her ombre glasses, darker on one side of her face, lighter on the other.

Moon has brought her own notes, taking the time to write out multiple sheets. She is a born writer, and Earth to Moon is not her first book. (I have her 2001 novel, America the Beautiful, on hold at the library.) Lucky for me, she’s also brought a sample of her delicious Moon Unit tea, a special “Earth to Moon” blend made in honor of the memoir. I drink it while I write this, hoping to bring even more of her to the page.

Why write this memoir now?

Moon Zappa: People always ask, “What was it like growing up with Frank Zappa for a dad?” I always felt it was Gail’s story to tell because she was the “adult” opposite my father. But after she died and threw the curveball of a lifetime, I didn’t feel like I had a choice. I would either be a cautionary tale about being destroyed, or I could be a victory story of survival and love getting to win. Oddly, I inherited Gail’s tenacity, and that is the endurance I used to tell this story.

I felt I had to tell a story about recovering what I felt was stolen from me as a sensitive, dutiful, loyal daughter in a really complicated family and household. The book, now that I’m on the other side of it, is a kind of portrait of toxic femininity, where you give and give until you’re ground into dust. It’s also a case study in nurture versus nature. I didn’t think that when I was writing the book, but reflecting on it now, those are some of the things I’m getting a chance to reexamine.

How difficult was it to write?

The complex PTSD is real. Revisiting painful experiences and trying to write it like a police report so the reader could have the visceral experience, the sensory experience, that was really important to me as a writer. And then as a daughter spelunking in hell, it was hard to look at, kind of like scaling Meru emotionally. I tried my best to not paint anybody in a bad light, but to just say what happened. I tried to share stories about my father that people haven’t seen before and to create a human portrait.

It seems if you want to be an artist, you must be unapologetically selfish and sacrifice your loved ones for the art, certainly in your father’s case.

And we didn’t have a say in it as kids. That’s the decision Gail made. It’s a formula that can work when there is acknowledgement of the other person’s sacrifices. But absent the acknowledgement or the perks of the sacrifices, it’s not okay. Not having the understanding or the bandwidth for the greater context and the experience and the consequences of it for the children in the household, is the territory I’m traversing. I ask, “Is genius worth the collateral damage?” I know my answer.

It didn’t occur to me that it was even an option that I could grow into an artist who didn’t drive or do laundry or pay a bill or nurture another person. When I became a parent myself, I was angry all over again because it is so easy to say, “I’m sorry.” It is so easy to give comfort when someone isn’t feeling well, or to support them when they’re going through a difficult time, or to show up for a school play, or an event that matters to your kid, or to reflect what their talents and attributes are and encourage those qualities. Some of the stuff is so basic.

Artists make decisions I would label selfish, and they can live with the consequences. I haven’t built up the ability to live with the effects of my actions because I lived it firsthand on the receiving end. But I do have a fantasy about trying to be selfish for a year, maybe just once a week.

Do you have thoughts on why Gail chose to remain with Frank?

I had a lot of empathy for Gail because I witnessed firsthand Frank’s treatment of her, which really bothered me. But that was her choice. When she became ill, I had no desire to attack her because I didn’t want to hurt her in any way, especially at the weakest time in her life. When she was diagnosed with lung cancer, I had a fresh wave of endurance because I thought there’s an expiration date on her cruelty. I just focused on being kind to her, and knowing that was my gift to her, out of respect that she was my mother. That was really easy to do. But when she threw the curveball, I had to relook at every definition I had about love, family, trust. I had to go back over events and wonder what secrets my siblings knew, what Gail’s motivations were.

I didn’t know we had such a horrible relationship. Don’t get me wrong—I knew we had a bad relationship. I saw many therapists who said, “Run for your life.” But I just kept saying, “No, no, what’s the solution to creating harmony with this person who I am not naturally compatible with?”

The quote at the beginning of the book: “Since my house burned down, I have a better view of the moon”—everything was destruction. I had to rebuild myself from those ashes. When I was doing the research [for the book], the surprise was finding even more empathy for her. Frank was gone so much. That’s not easy. We all became serial monogamists growing up in a house with a father who cheated so much. I don’t know how Gail did it. I couldn’t have withstood that.

In the book, you never call Gail “my mom” or “my mother,” but you refer to Frank as “my dad” or “my father” often. Were you aware you were doing that?

Oh, yes, I was very aware of it. I give some gravitas to the word when I finally am able to use it. I did not feel I had a mother. That was an act of generosity on my part, at her bedside, giving her fair due and recognition. For that brief moment when she’s either super high on whatever she’s on, or because some awareness kicks in, when she gifted me with, “What if you were always this nice?”, that was as close to a healing and an apology as I could have received. I savored it, and I really took it in. That’s why the reversal was such a shock to me.

I kept trying to explain to her the kindest thing she could do is clear and clean everything up so that we are not tasked with chaos on top of our incredible grief. She upended so many traditional ideas about obligation, about hierarchy, about how care travels in the family line, when caring for your children stops. From the time I was so small, I was literally signing contracts about us as a family and the family business. I like to joke that when you grow up in a family business, it leaves a mark, a trademark. The amazing author Mirabai Starr talks about grief literacy and what loss does—the things we can never look at or see or smell versus the things that we absolutely feel and have a “ride or die” attachment to. Not having the chance to go through Gail’s things and to know who she was and why she did what she did that was a big loss for me.

You weren’t able to go through her things?

No. By that time we were already in legal embroilment. I didn’t even know who wrote condolence letters. I had no idea who our support system was, if there even was one. There were so many things that were lost in the loss. My grief process was different [from] my siblings’ grief process, and then to be attacked and judged on top of that. I understood they were trying to go at a pace and they had obligations, but there was never a personal one-on-one sit down, just the promise of, “Anytime you want to have to sit down,” but then it never manifested. I’d run into people who would say “Oh, your sister was so sweet. She let me come to the house and take whatever I wanted.” I’d have to have my fists clenched in a ball and say, “I’m glad you had a positive experience,” but inside just burning with fury at the injustice of it. Again, everybody has their own version of reality, and as my ex-husband likes to say, “Everyone’s the hero in their story about themselves.” But when you are raised with that much dysfunction, you don’t think you’re the hero.

Is it difficult to talk about your parents honestly after they’re gone?

When my mother died, I felt robbed of the opportunity to grieve for her because her actions were such a shock to me. I was so blindsided by her final word that I’ve got layers of grief that are really hard to access. I can tell myself intellectually, “That’s her loss. Too bad for her that she felt that way.” My idealized version of grieving is that when you really feel a connection to somebody, of course it’s devastating when they die, but you internalize the best of them and you can still feel vitality from conjuring them. But not when they are vindictive and cause injury to the end and beyond. That’s hard to forgive.

In the book you never stray from telling your story strictly from your own perspective, which doesn’t leave room for anyone to contradict it as it is your singular experience.

It’s interesting what you’re talking about because I feel like the culture wants us to feel like everything’s our responsibility. There’s no such thing as the victim. We create all of our experiences. If you follow that logic, then why not eat totally toxic food and live in garbage areas? There’s a whole industry, hospitality, that is about making someone feel amazing. Again, that toxic idea of, “I’m responsible for my own orgasm.” Yeah, when I’m by myself, but if I’m with you, guess what? You’re also responsible. This is why we see theater and movies. It’s not all monologues. I mean, it is on Instagram and TikTok, but if you’re opposite a person, there’s some responsibility.

Were there any concerns about the well-known people you talk about in the book, or your siblings getting upset upon its release?

You can’t predict what people could take personally and get upset about. I hope they like what I’ve written and that it sparks memories about our shared history. I had always wanted to do a family memoir. When Gail was sick, I was really hoping we could all collaborate and tell a linear story and pop in whoever’s story was the funniest or most relevant for that time period and to have that lens on growing up. But my ideas were always shot down.

I thought I was close [to my siblings]. Again, I had to relook at what closeness is. The mindfuck for me is when I’m perceived as the one creating eggshells to the one who’s excluding me and competing with me instead of sharing love and our shared history and our shared memories. But I can’t control that.

I can imagine accusations of you cashing in on your family’s name with this book, but the cross-section of traumas you share are helpful to the many people who have experienced one or more of them. Your name might bring them the help they need.

I really appreciate that because I come from so-called “privilege,” and if I’m struggling with [the help of] many resources, what is somebody with little or no resources doing? How are they making sense of their world? I really appreciate the work of Brené Brown and how she talks about when you can name something accurately, it unlocks something and relieves pressure. Art and music and film and dance and so many other pieces of work where people just put their blood and guts into it, those things have been skeleton keys for me. I patchwork myself together looking for those kinds of materials with that level of depth. It’s bringing tears to my eyes to think about the media that has saved my life. If I could give language to something for somebody else, it’s my extreme pleasure to offer that.

Were there realizations that came out in the process of writing the book or after it was completed?

How disappointing it was to ask all the right questions of so many of the wrong people. I think of that book with the bird where he’s just traveling, looking at a dog going, “Are you my mother?” and then a bulldozer or whatever the hell he’s looking at. In some ways, the pursuit of self-help has been that unfortunate journey. But growth happens when you’re in pain and when whatever is happening is intolerable. Very often when you’re at your most vulnerable, you’re not going to be making the best decisions about what changes to make because you actually need outside help. It’s such a bizarre process. With an airplane, it’s never flying in a straight line. It’s always adjusting a little to the left, a little to the right. A little bit of failure, a little bit of success, straight line.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.