Photo-Illustration: Vulture; Photo: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

More than a year before Bob Iger shocked the TV universe in August 2017 by ending Disney’s licensing agreements with Netflix and announcing the creation of what would become Disney+, media analyst Matthew Ball pretty much predicted the whole ball game:

When the Netflix deal ends, I’d bet that the entire Disney catalog will instantly move to a new Disney O&O service. The fact that it was all contained, used and watched in one place not only creates a stronger ecosystem around Disney content, it gives the audience a single point of transition. All of a sudden — and nearly a decade and half after Netflix, Amazon Video and Hulu launched — we’ll have a massively scaled Disney subscription service…. The shift to Disney as a Service will be so significant because it will allow Disney to transform from a company about products, titles and characters to one that sells entertainment ecosystems. Instead of “hiring” Disney for 90 minutes or 30 pages, audiences will hire the company to tell them stories year round and across a multitude of different mediums and formats.

By the end of 2019, and the debut of Disney+, the basic thrust of what Ball had forecast came to pass. And barely a year after that, the “massively scaled” part also started looking pretty good, when Disney+ passed 100 million global. (The company now has more than 200 million global subscribers when you include its Hulu and ESPN+ platforms.) While Ball certainly wasn’t the only observer who realized Disney’s future was digital and not linear, the clarity and specificity of his writing back then captured the bigger picture of what was going on in streaming. Netflix was several years into making its own originals, and its success was obvious to most. But Ball understood that it would not have the market to itself for much longer, and in a series of essays, he sketched the rough outlines of what would become the streaming wars and the death of the cable bundle. So when my producers and I were putting together the final, streaming-focused installment of Land of the Giants: The Disney Dilemma, we knew we needed to talk to Matthew Ball.

These days, Ball spends a lot of time thinking about another big tech development — the metaverse. He even wrote an excellent best-selling book about it, a revised and updated version of which was released a few weeks ago. But in between stops on his book tour, Ball made the time to talk to us. And while a lot of his best points made it into the episode, when you spend an hour talking to Matthew Ball, soundbites will not suffice. Read on to hear more about what led him to write that 2016 essay, how the streaming wars have played out since, why Disney has done so well in streaming, and what challenges remain for the company.

In 2016 you published a piece essentially predicting what would become Disney+. What was going on in the industry when you wrote that article? What led to you thinking we were about to see the transformation of Disney?

I think what’s important to understand about the state of the industry in 2016 is that we were six years into the secular decline of pay television. Penetration peaked in 2010, and from that point until 2016, we had a shockingly consistent decline in traditional television consumption. Nearly every year we saw the same rate of decline that we saw the year prior, and throughout that interim period it was common to hear executives say, “The bottom has to be near.” And by 2016, 2017, and 2018 — when you had the entire industry reconfigure for the so-called start of the streaming wars in late 2019 — there was a growing sense that it actually was unstoppable. There was no bottom. After four, five, six, seven, eight years of consistent decline, you could no longer bury your head in the sand.

I think Disney in particular was first to recognize not only the inevitability of sustained decline, but their suitability to this new modality. In 2016, I noted that they had started to batch their licensing deals, most notably with Netflix, so that they would all expire at the same time essentially in 2019. Meanwhile, they had started to transform their entertainment ecosystems into recurring products. The Marvel Cinematic Universe was several years old at the time. It was still scaling to two and then three films per year. But with that, plus their comics subscription service, you started to get the sense that their IP ecosystems weren’t just about merchandising. They were about signing up customers to something they could experience every few weeks — very closely resembling the monthly model of Netflix.

And at that same time, they had launched a service called Disney Life in the U.K. and another few territories. That was very much the template for Disney+ today — and what many believe Disney+ will look like in the years to come — spanning not just streaming video, but also books and games, bundled into a single application. So I had made the observation that you could see where the industry was going at the time. Disney, though they hadn’t yet committed to launching a streaming service, seemed to be strategically timing their licensing deals for the flexibility to launch a service, doing some of the originating technical work and then even testing customer interests in myriad foreign markets.

So there was a lot of movement toward streaming well before D+ finally launched. Were you talking to people inside Disney then about the need to evolve from linear?

I wouldn’t want to comment on any private meetings. But I think one of the challenges with the persistent narrative that Hollywood was behind and resisting the changes — it’s a question of who you were talking to at these companies. There were individuals, typically the younger cohorts, that very much believed that streaming was the future. They had experienced it as young adults themselves and were itching to find a way to push forward their company’s own endeavors into the category. What everyone was trying to do was to time it perfectly. They didn’t want to give up the revenues from their existing business to cannibalize it for another modality that was years away from maturation.

At the same time, they didn’t want to time it so perfectly that they could never catch up to the market leader at Netflix for years and years. Every conversation inside a big media company was the same. Most in Hollywood already bought that, at some point in time in the future, streaming would be the dominant way to access media and that IP ecosystems and multi-prong strategies were going to be essential. The debate was around timing.

Before it tried to compete with Netflix, Disney — like all its rivals — helped Netflix build its business by licensing content and IP to them. They obviously felt like the end of the cable bundle was still far enough away that they could afford to take the Netflix cash in the short term. Do you buy the conventional wisdom that this was a mistake?

I think it was an understandable mistake. I think the greater strategic error was how long they waited to actually launch a streaming service. And I think this is actually an incident in which the entire industry collectively harmed itself. When you take a look at the start of the streaming wars — there’s no official date of course, but we tend to discuss it as starting at the end of 2019. That’s because we had, in a matter of weeks, Apple TV+ then Disney+ launch. In the second quarter of the following year, we had Quibi, we had HBO Max, we had Peacock. And by the end of that same year we had the introduction of the rebranded CBS All Access as Paramount+.

So it’s not just that Netflix was enabled for too long and it’s not just that traditional media was too slow to launch their streaming services. It’s that they all waited until it was too late, all launched at the same time, and therefore made it harder, more expensive and more patience-testing for any one of them to thrive and succeed. They launched at a time of peak competition with peak pressure on pricing, with peak pressure on talent relationships, and that meant that churn was much higher, revenue per user was much more modest, the strain on a balance sheet was harder still, and shareholder scrutiny was about to be higher than ever. That I think was the biggest strategic error. Had any one of these companies launched, I think, a year or two earlier? I think we’d have a very different landscape today.

When Disney+ launched, the company’s focus was on getting as many subscribers as possible as quickly as possible. So it made a ton of original content across a whole bunch of genres, and it priced the service very cheaply. The focus now is obviously on profits, but to do that, it seems as if Disney has had to give up the idea of making D+ as ubiquitous as Netflix. In other words, Disney+ isn’t going to be for everybody. Can you explain this a little more?

The perspective that Bob Iger seems to have today is that it was always a mistake to go after every customer worldwide. And that’s not just because it’s expensive and the margins are thin. It’s not just because that’s not the bread and butter of Disney+. But it’s that they believe that for between a quarter and a third of everyone in the United States and many countries around the world, Disney+ is an absolute necessity for which the pricing power is enormous, and the content requirements are not that high. In the United States and Canada, there’s close to 40 million homes that have at least one, sometimes two, three, or four children. And Disney+ is not optional for them. But for the remaining 100 million homes in the US and Canada, Disney+ is a choice, a choice alongside five, six, seven, eight, nine other services, some of which are free. And Iger seems to have concluded that focusing on that customer basis — it’s not in their interest and it’s actually quite costly.

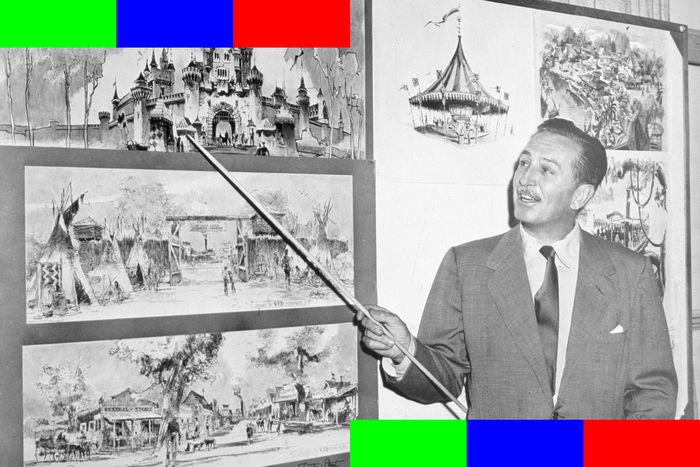

You’ve written a best seller about the Metaverse, so I’m curious how you think this new tech will help Disney evolve in the coming years? I think you’ve suggested in other appearances that both streaming and virtual reality can help Disney achieve some of Walt Disney’s original vision. Explain that a little bit more.

One thing that I think time has forgotten is that Walt never really envisioned the business as just about the production of linear content. I don’t just mean referencing his famous 1957 diagram of the Walt Disney Company flywheel. Even when you go to the first feature films that they produced, he always imagined that content experiences were transformative, that they were felt in the real world. If you can believe it, Fantasia, a film premised upon synesthesia, was the second feature film the company ever released. The very first Snow White was a remarkable achievement in animation, certainly. But to launch the film he actually transformed the area around the theater into an immersive version of the universe that he had drawn. There were life-sized dwarfs. It was simulcast across multiple radio networks in the United States. The success with that program actually inspired the creation of Disneyland, 20 years later.

Disney has spent a hundred years imagining its stories as bringing fantasy and escapism to the everyday American. We can now produce not just “Disneyland in virtual spaces,” but versions of Disneyland that can do what Disneyland can’t. It’s not stuck to the laws of physics. It doesn’t close at 10 p.m. It’s available to every person globally. These are never going to mean that the park experience as we know it goes away. But it can certainly offer things that the parks can’t today, and certainly to more people. How that intersects with the products that we know and love today, Disney+ included — that’s not yet known. But we’re starting to see that. It’s no surprise that the first major content investment by Apple with its Vision Pro device was part of the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

Let’s zoom out a little. We have been hearing about the streaming wars a lot over the past five years — and more recently that they’re basically over, with Netflix the clear winner. Was the phrase “streaming wars” the right way to talk about what happened over the past five years?

I have always found it interesting, if explicable, that certain executives would downplay that there’s a war in streaming. There is a war. We can see that now. There are winners and losers; there are combatants slain on the battleground; and there is a growing consensus that we were optimistic about how many successful, scaled streaming services there would be. We were optimistic about how profitable they will be. And so this question of who is going to survive is important. The difference between being the second and third, or the fourth and fifth-largest company, mattered in the heyday of pay TV — but it didn’t matter all that much. If you were 10 percent smaller than CBS, as NBC, you were less profitable probably, but not that less profitable. But being in third or fourth in streaming makes a heck of a difference. And if you’re eighth, you’re probably not long for this world.

Would you say that Disney has proven that it’ll be among the victors?

I think Disney has definitively proven that they’re going to be among the few victors. They have more than doubled their price since they launched a price increase. Despite that fact, they are the second or third-largest streaming service by total subscribers depending on your measurement. And that growth has been sustained despite what many considered to be among the weakest years in their content offering. Marvel Studios is not on fire as it used to be. The Star Wars franchise has not had a motion picture for five years and feels weak on the television side. And Pixar, though recently revived, went through its hardest period in a quarter-century. The fact that Disney+ endures and has grown and has become more profitable is evidence of the durability of that brand, that content offering, and its appeal.

At the end of the day, one of the core problems with the streaming wars was that outside of the bundle, every company was a choice by a customer. And while every company preferred to be one of the largest and most profitable direct-to-customer subscription services, very few of them had an inherent reason to exist. Netflix didn’t have an inherent reason to exist, but they earned it by being first, by moving most aggressively, and through 15 years of the most remarkable excellence the entertainment industry has ever seen. But for other brands, which I’ll not call out individually, it was a harder sell. No customer sat there saying, “I want all of the films and TV series from that studio or this studio” or “I want to surround my child’s life with the IP of that 80-year-old studio.”

But Disney was the exception. While most customers would say, “I’d rather watch everything through Netflix, the service I already have, on a tile beside the shows I already know and like, on the app that I’ve already installed and logged into on every one of my devices,” there were a lot of people, especially parents, who said, “You know what? I would like a Disney service. Why? Because I trust the brand. I trust the quality. I like navigating its interface through characters rather than just genres. And I trust my son and daughter inside the app, something that I don’t trust with nearly any other alternative, especially the other top streamer for kids, YouTube.” And so I think that that theory has been born out pretty cohesively and clearly. There are few customers who will say they’re happy Disney’s price has doubled since it launched, but I think most will tell you that they can’t imagine getting rid of it as long as they have kids.

See All