On the Shelf

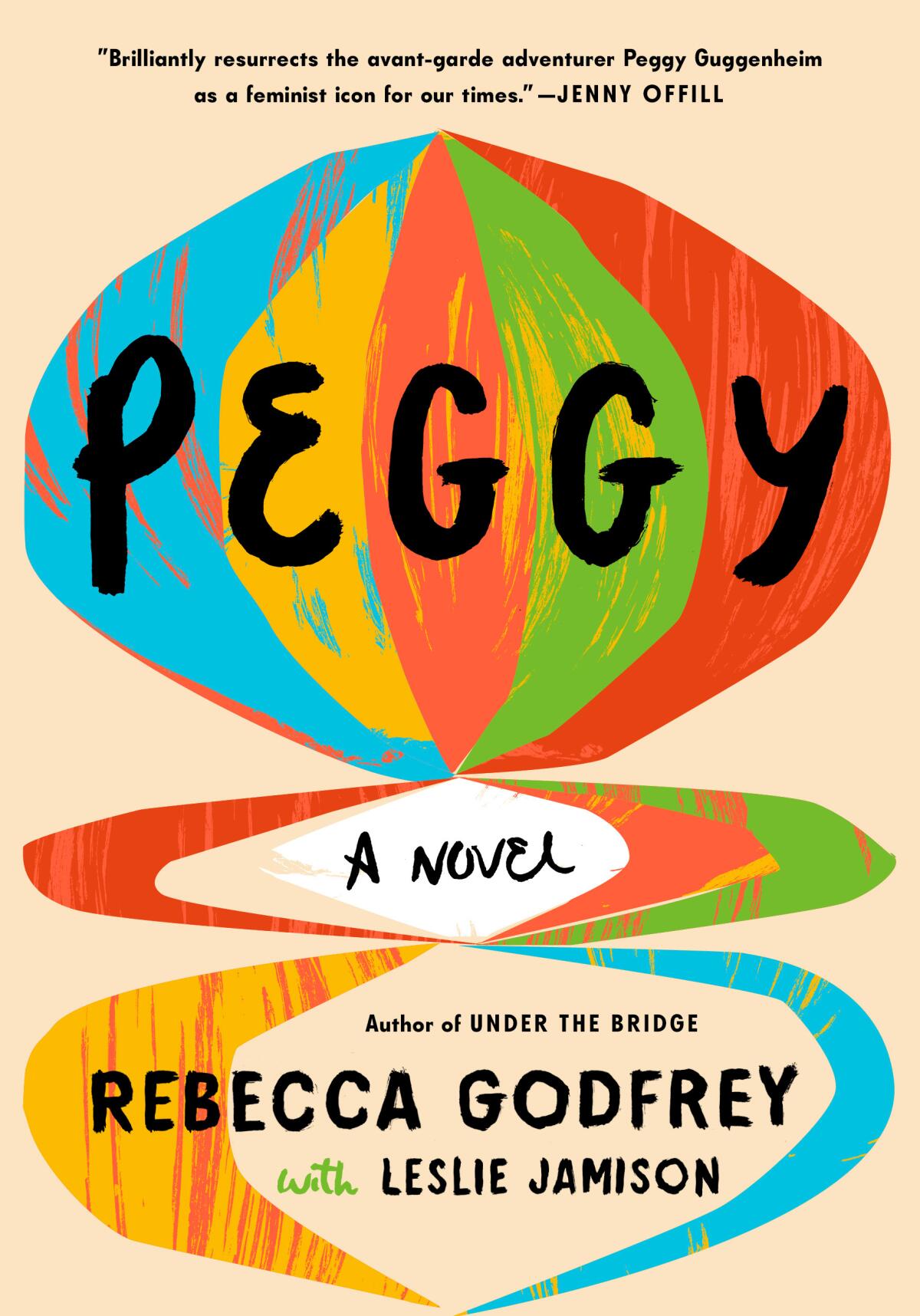

Peggy

By Rebecca Godfrey and Leslie Jamison

Random House: 384 pages, $29

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

How does one put aside grief to finish their late friend’s book? That was the conundrum Leslie Jamison faced when completing Rebecca Godfrey’s novel following her death from lung cancer in 2022.

Jamison is best known for her essay collections “The Empathy Exams” and “Make It Scream, Make It Burn” and her unflinching memoirs “The Recovering: Intoxication and Its Aftermath” and “Splinters,” published earlier this year. Godfrey was the author of the novel “The Torn Skirt” and the harrowing nonfiction book “Under the Bridge,” which was adapted this year into a Hulu limited series starring Lily Gladstone and Riley Keough — playing a dramatized version of Godfrey. “Peggy,” a fictionalization of heiress and gallerist Peggy Guggenheim’s life, is Godfrey’s third and final book, which she wrote during the final decade of her life. She died before she could complete the last act. That’s where Jamison stepped in.

The two met at Columbia University School of the Arts, where Jamison directs the Master of Fine Arts nonfiction concentration and Godfrey taught a unit on anti-heroines.

“Under the Bridge” author Rebecca Godfrey focused her final novel, “Peggy,” on the life of gallerist Peggy Guggenheim.

(Brigitte Lacombe)

Jamison describes the class as an “institution” within Columbia. “An anti-institutional institution,” she laughs.

It’s for this reason that Godfrey was drawn to Guggenheim.

“Rebecca was interested in women who disrupted things. Peggy was a bit of a disrupter. She liked artists that a lot of people didn’t like. She lived as she pleased.

“Part of what makes an anti-heroine an anti-heroine is that they’re not implicated in the same kinds of marriage plots that other heroines are implicated in,” Jamison continues. “They find their intimacies not necessarily in the stability and resolution of marriage but in love affairs and chosen family and friendships with women.”

Their admiration of unconventional women who prioritized sisterhood is what connected Jamison and Godfrey too.

“There was a way that friendship and intimacies with women in this novel [were] connected to Rebecca’s conception of an anti-heroine and how Rebecca lived her life,” Jamison says.

Though the two knew each other for less than five years, Godfrey and Jamison’s friendship was an intense one that spanned many “radio channels,” as Jamison puts it. “There was a kind of urgency and fervor to our friendship in those early days that had to do with the fact that she was already sick.” Godfrey was diagnosed with Stage 4 lung cancer in 2018 and given six months to a year to live. Godfrey survived for another four years, which Jamison, in a New Yorker essay, attributed to Godfrey’s “continual fight to steal another few months of life.”

One of those frequencies inevitably turned to discussion of “Peggy” — out Tuesday — and whether Godfrey would be able to complete it. “If she only had a limited amount of time, what did she want to do with it and how did she reckon with wanting to spend all of her time with her daughter and all of her time with her book?”

Though Godfrey never outright turned to Jamison to finish the novel, “it was an honor to be asked [by Godfrey’s literary agent and executor, Christy Fletcher], and a daunting task,” Jamison writes in the book’s afterword.

When it became clear that Godfrey likely wouldn’t see “Peggy” come to fruition, she left instructions with friends and family about how she envisioned it concluding.

“She didn’t want a truncated [version of it with a] note that says, ‘It ends here because Rebecca died.’ She wanted a version that could feel like a complete work of art,” Jamison says.

In order to do justice to that version, Jamison “steeped” herself not only in historical material about Guggenheim, but in Godfrey’s own voice and Godfrey’s version of Guggenheim.

“I’m not even trying to imagine Peggy’s subjectivity, I’m trying to imagine Rebecca’s subjectivity of Peggy’s subjectivity!”

“My worst nightmare was that I was going to drive Rebecca’s voice out of the book with my own work,” Jamison says. Ultimately, she had to push any hesitance or tentativeness out of her mind. “In order to inhabit her vision I had to leave deference behind and take a swing.”

Still, Jamison found the “triangle” of herself, Godfrey and Guggenheim easier than if she had been working alone within a “dyad” of Godfrey’s “fictive construction.”

“I would have felt like I was trying to crawl inside something that absolutely wasn’t mine,” she says.

“Finishing the draft was harder than writing the draft,” Leslie Jamison says. “Closing the document was the time that the grief felt most acute to me.”

(Grace Ann Leadbetter)

The hardest thing for Jamison, as one might imagine, was combating the grief she felt after the loss of her friend while “ghostwriting, in every sense.”

“[Working on the book] made me feel close to her,” she says, recalling times when she wished she could send a quote or anecdote from her research to Godfrey only to find that Godfrey had already discovered it and highlighted it, such as a 1938 letter Guggenheim penned to her friend, novelist Emily Coleman, about spending time in Paris “working hard on my gallery and f—ing.”

“I thought, ‘Rebecca would have loved this line.’ And she did!

“Finishing the draft was harder than writing the draft. Closing the document was the time that the grief felt most acute to me. I wasn’t expecting to feel this acute stab of bereftness when it was done.”

There’s a line partway through “Peggy” in which the titular character calls art “a living thing,” and one can’t help but think of this book as a living thing. Jamison agrees, adding that every work of literature is a living thing.

“There’s also a way that this book feels like a living thing insofar as Rebecca is no longer alive,” Jamison says. “This book is not her, ‘Peggy’s’ not her, but it is this thing that she made, it contains so much of her, and so it feels like it’s a part of her that’s very much still with us.”