And so the two weeks when I become interested in athletics every four years have drawn to a close, with a ceremony to mark the occasion. There were many ceremonies along the way, of course, and the Olympic Games are themselves a sort of ceremony writ large, a ritual against which the athletes of Earth measure their worth — though obviously they are busy with international competitions in the years between games, winning medals and trophies and setting world records. But the world has agreed that this is the Big Show, as the world agrees on little else.

Since this is technically a television review, let me just say, before we get to the spectacle, that what came between the opening and the closing, as something to see, was exceptionally well presented — at least if you were watching via Peacock. (I can’t speak to NBC’s broadcast coverage, apart from the opening ceremony, where the commentary was intrusive and uninformative, and the closing, about which more below.)

It was a platform one could dive from in any direction, a well-executed interface that allowed one to follow any sport in any number of ways — everything, anytime, from before the beginning of an event until well after the end, into what I think of as the hugging round. So many hugs! All that goodwill and affection, not just among teammates but between competitors, who represented diversity among and within nations, whatever the peculiarities of their individual governments and nativist movements. It’s a world you want to live in. (The Olympic spirit: It’s not just about the gold, silver and bronze.) An illusion, perhaps, but as Marlene Dietrich said, “You can’t live without illusions, even if you must fight for them.”

One of five giant Olympic rings moves into place during the closing ceremony of the 2024 Paris Olympics at Stade de France.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

As for Paris, the staging of the games — and “staging” feels like the right word — in and around the central city felt inspired, somehow at once very old-fashioned and brand new. To be sure, there were parts and people of Paris that remained unseen, if not intentionally hidden. But erecting temporary open-air stadiums below the Eiffel Tower, in the Place de la Concorde and in the gardens of Versailles demonstrated that a host city might have something to show the world outside — literally outside — its big arenas, something essential to the spirit of the place. (Though, with its many parks and large public spaces, it might be better fitted to the task than any other city.) Putting swimmers in the Seine might not have been the healthiest idea, but it had a look. Races run over crooked cobblestone streets, crowded with spectators, were doubly exciting for being run over crooked cobblestone streets, crowded with spectators.

At last to the closing ceremony: It was almost by definition an anticlimax, given that the games were over — if not yet “officially” over — and every race had been run, if only just barely. (The women’s marathon winners received their medals during the ceremony.) But given artistic director Thomas Jolly’s idiosyncratic opening show, set upon the Seine, one would have expected something interesting, if not on its own explicable. If the opening was an often confusing but certainly stimulating cavalcade of images and events, the closing was presented as a single, stately, snail’s-pace theater piece — something like Robert Wilson directing the Cirque du Soleil. It was bookended by a prelude in the Tuileries — where a choral rendition of Edith Piaf’s apropos “Sous le ciel de Paris” accompanied French swimming champ Léon Marchand taking a bit of Olympic flame to pass on to us — and a Gallic version of a Super Bowl halftime show, anchored by the band Phoenix.

Alain Roche plays a piano hanging vertically during the closing ceremony.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

The central piece had to do with the founding and revival of the Olympic games, and began with a golden winged figure descending to an abstract Earth to meet, after a solo dance passage, the silvery rider and still-mysterious hooded torch-runner we saw in the opening ceremony, the latter carrying a pole from which the Greek flag unfurled. The Voyager discovered the long-lost Olympic rings. Opera singer Benjamin Bernheim, in a robe made from recycled VHS tape, sang the “Hymn to Apollo” accompanied by Alain Roche, playing a piano suspended in the air, perpendicular to the ground. Numerous gray figures exhumed giant rings, which rose into the air, one by one, while performing tricks upon their interior scaffolding. An (inflatable?) replica of the “Winged Victory of Samothrace,” as famously found in the Louvre, rose from the floor. Lights in the stands — from wristbands worn by the audience — produced giant animated athletic events as one might find painted on a Greek vase. The five airborne rings arranged themselves in the familiar Olympic pattern.

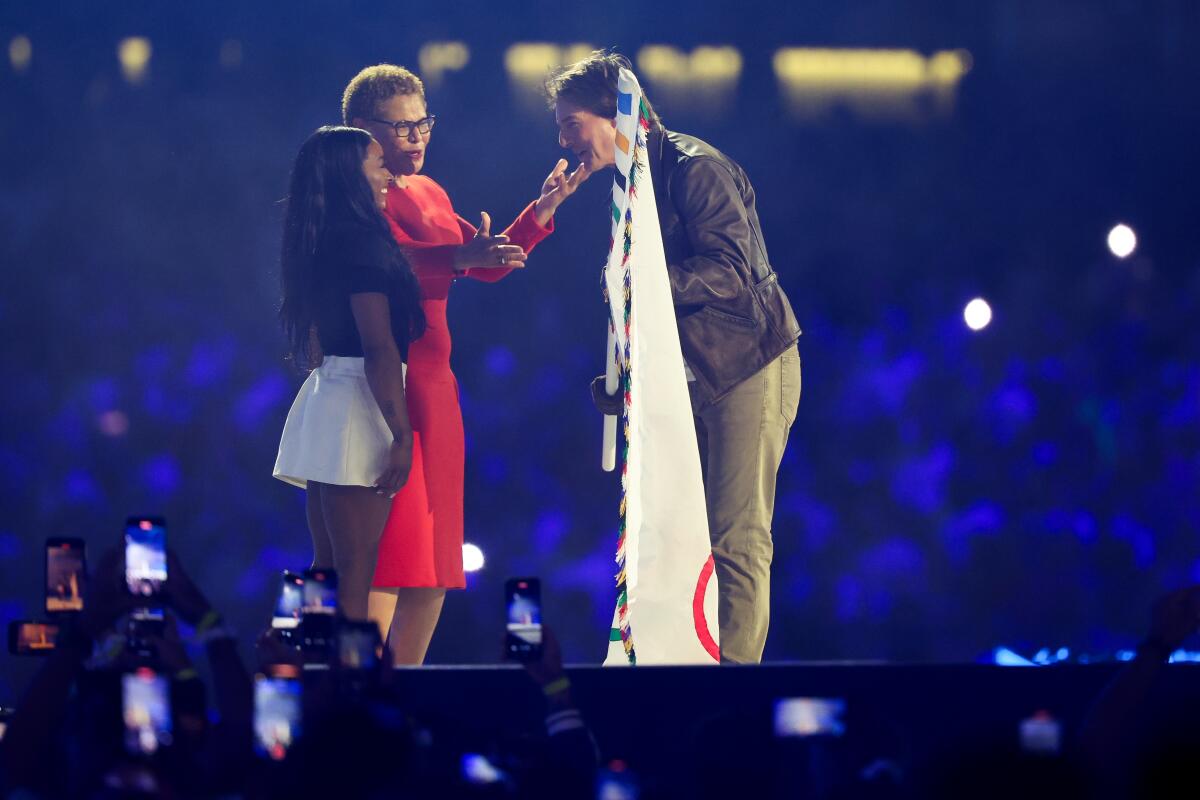

Then came pyrotechnics, the pop show and the protocol — speeches (lovely, generous), declarations, lowering the Olympic flag and turning the games over to the 2028 host. H.E.R., sporting a white Stratocaster like the one Hendrix played at Woodstock, performed “The Star-Spangled Banner,” demonstrating once again that it’s a song best handled by an R&B singer. Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo handed the flag to L.A. Mayor Karen Bass, accompanied by America’s gymnast sweetheart Simone Biles, and the show went jarringly Hollywood.

Tom Cruise takes the Olympic flag from Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass and gymnast Simone Biles during the closing ceremony.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

Tom Cruise, whose status as an international superstar was enough to excuse his presence, abseiled into the stadium, took the Olympic flag from Bass and Biles and drove off with it on a motorcycle, out of the Stade de France and into a filmed piece in which he rode into a cargo plane, skydived into the Hollywood Hills and affixed three extra O’s to the Hollywood sign to create an image of the Olympic rings. He passed the flag on to a series of Olympians: first, cyclist Kate Courtney, who passed it to Olympic sprinter Michael Johnson, who passed it to skateboarder Jagger Eaton, who arrived at Venice Beach. Then the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Billie Eilish and Olympics ambassador Snoop Dogg performed in another filmed piece — recorded in Long Beach, actually — that looked like nothing so much as an MTV “Spring Break” special. (I’m pretty sure those palm trees were trucked in.) Aesthetically, it was like leaving a dark theater after a mysterious foreign film and walking to bright sunlight in a noisy American mall.

Happily, things did not end there. We returned to the darkness of the Stade de France, where the French singer Yseult performed an unusually subtle, sensitive version of “My Way,” whose English lyrics are by Paul Anka, but whose music, by Jacques Revaux, is French. (The original, “Comme d’habitude,” has lyrics by Gilles Thibaut and Claude François.) In case you wondered, why “My Way”?

The commentary was no less inessential with the addition of Jimmy Fallon, who also has a show on NBC.

Yseult performs “My Way” during the closing ceremony.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)