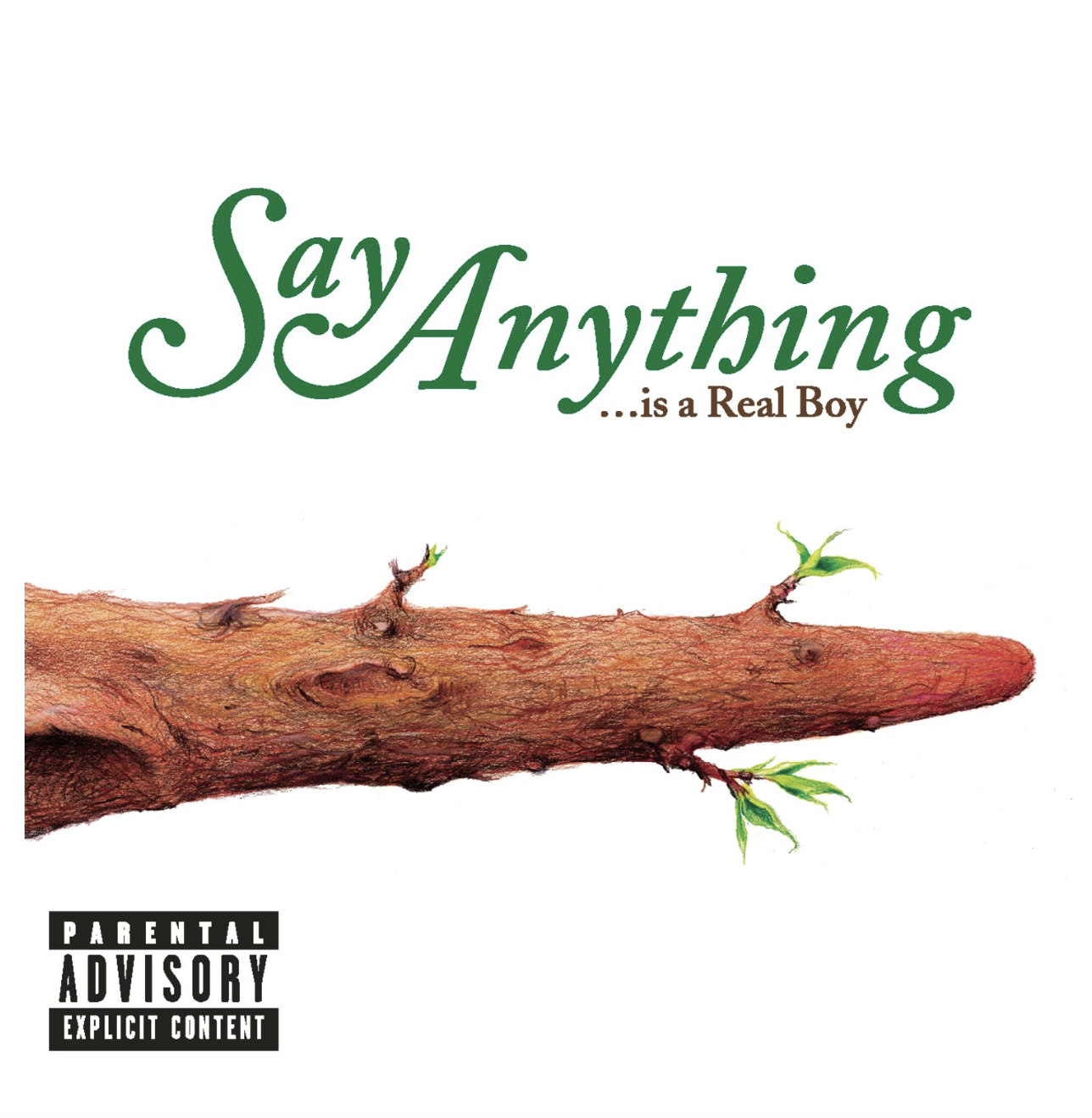

It was the early 2000s: emo music was making its mark on the world, and Say Anything’s Max Bemis was creating a masterpiece—while simultaneously losing his mind.

While the band has since cemented its place as an emo luminary, …Is a Real Boy was undoubtedly unlike anything else that came out of the scene around that time.

More from Spin:

- Universal Lands Film Adaptation Of Britney Spears Memoir

- Blood’s ‘Loving You Backwards’ Is Confounding and Often Thrilling

- Tomin Breaks Down the Building Blocks of Jazz

Between a self-proclaimed “fucking mess” singer, a fresh-out-of high school drummer, and two Broadway pros, Tim O’Heir and Stephen Trask, (Hedwig and the Angry Inch, anyone?) who had zero doubts about a certain 19-year-old’s talent, they created a beloved album that felt mature yet immature, serious yet sarcastic.

Musically, Bemis took things into his own hands, playing every instrument except drums (he left that to Coby Linder)––and pouring everything he had into this album as his mental health was plummeting, experiencing a mental breakdown, psych ward stint and all.

With unforgettable songs like rock-opera-esque “Admit It!!!,” wistfully horny “Every Man Has a Molly,” and Holocaust-inspired “Alive with the Glory of Love,” this album has stood the test of time. Whether due to catchy melodies, unforgettable lyrics, or teenage nostalgia, …Is a Real Boy remains a fan-favorite and a staple in the emo scene. The band will perform …Is a Real Boy at When We Were Young 2024 (the modern-day answer to a lack of Warped Tour), and they are in the midst of the album’s 20th anniversary tour, picking back up this fall.

We spoke to key players in the inception of the album –– including the notorious Max Bemis, Broadway alums turned producers Stephen Trask and Tim O’Heir, Doghouse Records label founder Dirk Hemsath and employee David Conway ––to dive deep into their relationships and the making of this record.

Twenty years after its release, we look back on …Is a Real Boy.

Meet Max

Max Bemis, lead vocals: We’re talking about …Is a Real Boy, right?

Dirk Hemsath, founder, Doghouse Records: I got a CD-R in the mail with a courier. It was from a friend of mine that worked at a major label. She basically said that she loves this and she thinks this kid is a genius, but “it’s way too left of center for my major label that I’m working at…but I think it’s something special, and I think you should check it out.” It was Say Anything demos.

I talked to him [Max], and we talked a lot, and I told him how much I loved the music, and he sent me some additional music, and I think I signed him without even meeting him, which was the first time I had ever done that.

Tim O’Heir, producer: I’ll give you the introduction to Max. I have a loft in Williamsburg, and it’s 2002 or 2003. I think he’s still in school at Sarah Lawrence, and he’s very gregarious. I asked him if he wanted to play a couple of songs, and he says, “Yeah.”

So we give him an acoustic guitar, and he proceeds to break most of the strings on the guitar in the first song by basically attacking it. He would go to strum a chord, but his pick would go underneath the strings and pull up as hard as he could. I’m like, ‘What are you doing?!’

Stephen Trask, producer: Tim sent Max to me. I was living in New Haven at the time, and Tim and I had just built a one-room recording studio in my garage. I think he [Max] took a train to New Haven, and he came, and we hung out. He sat in my studio and played me songs on an acoustic guitar, and he was very frantic and super energetic and punk—and I just thought he was amazing, and I knew I was in.

Tim O’Heir: I said to him [Max], “Who do you want to be? I mean, do you want to be playing for high school kids, or do you want to be Springsteen?” And he looked at me, and he goes, “I want to be Springsteen.” And then I never heard from him. Maybe six months passed, and I got a call from Dirk from Doghouse, and he says, “Hey, Max, wants to make a record with you.” And I said, “Really? I thought I scared him away.”

David Conway, Doghouse Records: He slept on my parents’ couch in Boston for a while. The things that stand out are so unique. I remember he folded blankets when he left my parents’ basement, which stood out to me as something that I didn’t think a punk rock artist would do. I remember a somewhat terrifying habit of Slim Jims, and even at the age of 20, 22, whatever I was, I was like, “Can someone survive on this many Slim Jims?” But I remember seeing him work in my friend’s studio. That was the moment where I realized he was like, this kind of, I’ll say, mad genius.

Dirk Hemsath: He set up in the middle of a record store and just played. And I remember thinking, I mean, it sounds maybe a little hyperbolic, but I remember thinking like, “Oh my god, this must have been what it was like to see Bob Dylan when he was young,” with this lyrical content, and the way that he just was pure emotion and these super mature songs, as far as the way they were put together, and for being such a young person. I just remember being blown away.

…Is a Real Boy, The Musical?

Stephen Trask: Max really wanted the album to feel like a cohesive story, and he was really into Hedwig, and he liked that connection. In his mind, it [the album] was a bit of a musical. I mean, my background was as a songwriter, not as a record producer.

Max Bemis, singer/songwriter/multi-instrumentalist: It was definitely supposed to be a musical. We were writing a script, and it was going to be like War of the Worlds between the songs and talking and going like Rent, but fucked. I mean, Rent is already fucked, but I guess it would be like actually Fucked.

It kind of sounds like a Broadway Jewish musical, So I feel like there’s enough about it that is musical-ish. I remember when, like, My Chem[ical Romance] put out the Black Parade, and, this is embarrassing, but I actually called my agent. I’m like, “Did they just corner the market on, like, musical emo music? Because I think they just did it. I don’t know if there’s room for us.”

Tim O’Heir: We were going to use [Stephen’s] studio in Connecticut and move to Brooklyn and do most of the work at my house and do the pre-production up there. So Max and Coby, who was the drummer, he was 17. He was very young and naive, but an amazing drummer, just incredible. So the two of them were thrown into a rehearsal space, and we worked on some songs and whatnot. Played every day. Then I recorded, and we listened back to it. During those few days, I started to get an insight into Max and what he was about and what was going on in his brain, which was incredibly difficult.

Creating Art, Losing Mind

Max Bemis: I felt an unhealthy level of psychological torture, pressure that was beyond even, you know, when you see Dewey Cox or something, or you see Spinal Tap, and you’re like, “Damn, these guys have lost it.” I lost it. You know what I mean? But it was through this prism of irony and laughing at all of it and laughing at myself. I think I probably would have died and got addicted to a lot of drugs, but I would have carried it off longer if I didn’t find it very funny, alarming, and sad the whole time.

Certainly, I was lost in that ambition of making a great record—and technically, it was our second record, but it was our first record anyone would hear. I wasn’t sleeping with groupies every night and railing cocaine all the time. I just was an unstable person who really wanted to do something positive for the world.

Stephen Trask: I’m not an engineer like Tim. I mean, I can do it now, but I’m not like he is. But I’m good at things like arrangement ideas, although really, Max had it all in his head. So, some of it was suggesting, and some of it was editing. He had so many ideas, and almost everything worked. So it was, how do you add to it without ruining it? Or how do you say “no, not that bit” and encourage good vocal takes.

Tim O’Heir: I worked with a lot of really talented people, supremely talented people, and I’m very lucky to have worked with them, but I never worked with anybody like Max. I started to think, this guy is a real genius. He really is.

Tim and Stephen: The Surrogate Fathers

Max Bemis: Considering I lost my mind, and I was a fucking mess…me and Tim butt heads sometimes, but he was like a dad to me. He recognized my… I don’t really believe in the word “talent”…but whatever it is that I had going on. Him and Stephen were like big brother surrogate fathers…also we couldn’t fake how into it we all were. We were literally creating magic, whatever it was, in our room together, and it was just fun. So I do feel lucky.

Stephen Trask: Max became sort of like a surrogate son to me. I was just very emotionally invested in Max. By this time, he had lived in my house, and we had worked together every day for quite some time. At a young age…his mind is working at this genius level that I don’t think his heart could process everything that his mind was going through. His emotions weren’t able to keep up with how fast his brain was spinning.

Lyrical Genius (But Maybe Not God’s Gift To Earth )

Max Bemis: Man, I was so just loving it, and just high on marijuana the whole time. I wasn’t like, “I’m God’s gift to songwriters.” I was like, “This is the best thing I could do right now, and it sounds exactly the way I wanted to fucking sound. Jesus, these people are good at their jobs. Actually, I’m doing pretty good too. This might actually fucking work.” And that was an exalting feeling.

Tim O’Heir: I even listen back now and I’m still totally satisfied with all the sounds that we got. He would kind of tell me where he was going, and I would do my best to facilitate that for him. So my role as a producer was helping him kind of tighten up the arrangements, but trying to figure out how I could facilitate everything he wanted to do.

I’d never worked with anybody that had that much foresight and vision into what they had come up with. I was kind of “Mr. Indie Rock,” and if the magic happened, it was magical. Not methodical as this kind of thing. This man [Max] was like Mozart. He was a composer. It was in his head. If he could write music, he would have written reams of it, but it was all in his head, and the only way he could get it out was via his instruments.

Max Bemis: [about “Alive With the Glory of Love”] Any person in a band has had the thought, when you write your best song, “This is the best song I’ve ever written,” and if you’re a good person, it’s within an objectivity that they actually prove to be true…It wasn’t just like, “I have God’s gift for writing this poignant Holocaust song.” I remember—and I still feel like this when I write something I’m really proud of—feeling, like, tired. Just good, fuck. I’m gonna have to really pursue this because there’s no denying that this is good. This is good.

I had to sit there for like, three hours writing. It came out all in one go. All the lyrics came out, and I was, like, crying, but it’s always been, like, a sense of some kind of irony to it. You know, that song is about the Holocaust, but it’s self-consciously, you know, I guess maybe toying with the fact you’re not supposed to sing about the Holocaust, or make a love song, or sex song about the Holocaust, especially.

And, Scene.

Stephen Trask: I thought people were going to flip the fuck out when they heard this [the album]. It was so smart, just the arrangements and the imagery and the metaphors and the poetry. It had the verbosity of what Tim would call “word rock,” except it was actually very concise and organized and smart.

Max Bemis: It’s a very humanistic album. It’s not nihilistic. It’s not about “Fuck the world. I’m crazy. This is my mission statement, where I go to the hospital.” It’s about having hope…whatever that means.

Stephen Trask: Recently, I was getting a piece of equipment repaired in New Haven, and I’m talking to the repair guy, and he says, “It says here, Sinjin studio,” and I said, “Yes, just a name I made up.” He said, “Oh, because my favorite album in the world was partly recorded at a place called Sinjin Studio. And I said, “Is it Say Anything …Is a Real Boy?”

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.