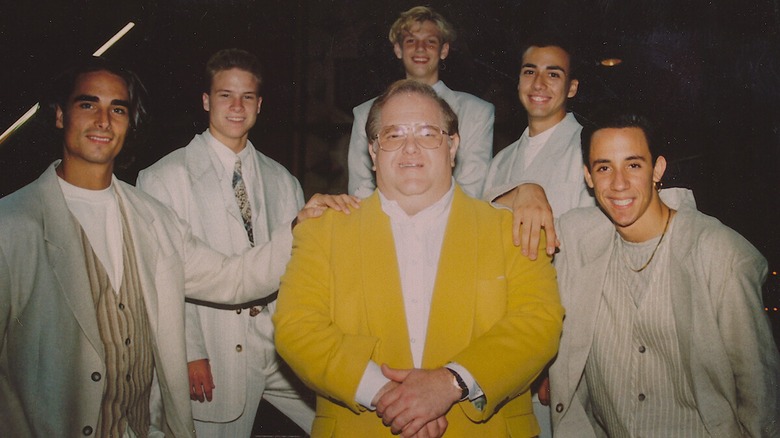

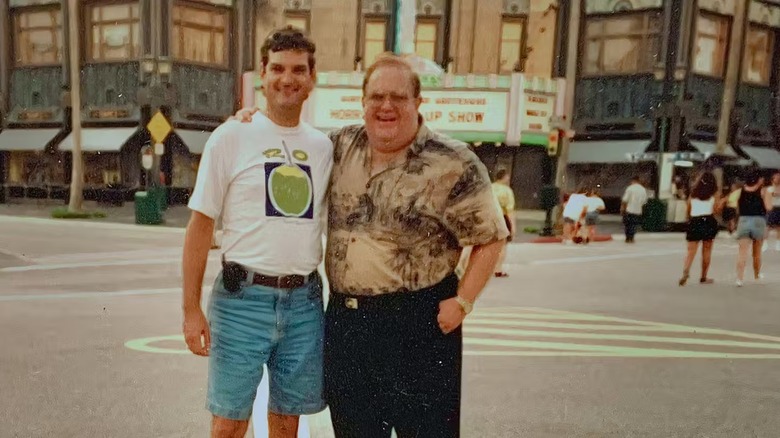

Netflix’s “Dirty Pop: The Boy Band Scam” is not the first documentary to chronicle the crimes of scam artist/music manager Louis Pearlman, who funded ultra-popular ’90s boy bands like the Backstreet Boys and NSYNC. Before Pearlman’s long-running Ponzi scheme was exposed, he was viewed as an ambitious businessman steering the boy band industry to new heights — until, of course, the walls of deception came crashing right down. It is not surprising that Netflix would release a documentary about an infamous scam artist who raked up debts of more than $300 million. However, it is odd that the showrunners have opted to use AI for voice and image-replication of the late Pearlman to create manipulated footage, which has been wedged between research-backed archival evidence and context-rich interviews peppered throughout the documentary.

The use of AI to create the altered footage is disclosed upfront. In fact, the first episode opens with genuine archival footage of Pearlman sitting at his desk, but we soon hear him speaking and addressing the camera. This is when the documentary discloses that the footage “has been digitally altered to generate his voice and synchronize his lips,” where the words uttered have been lifted directly from Pearlman’s book “Bands, Brands, & Billions.” Pearlman continues to “speak” via this AI-altered footage over three episodes, evoking an uncanny valley effect that does not feel warranted in the slightest.

This has not stopped the documentary series from sitting at number one in Netflix’s Top 10 U.S. TV Shows list. However, the implications of AI usage — both disclosed and undisclosed — in a narrative medium that hinges on objective fact-checking and corroborated evidence sets a dangerous precedent that should not be ignored. Let’s have a look at what the producers of “Dirty Pop: The Boy Band Scam” have to say about the matter.

How Dirty Pop: The Boy Band Scam used AI-altered footage

One of the docuseries’ co-executive producers, Michael Johnson, spoke to Netflix TUDUM to explain how the showrunners were “excited to push the envelope with new technology” to tell this important story “in the most ethical way possible:”

“First and foremost, we wanted to utilize this new technology in the most ethical way possible as an additive storytelling tool, not as a replacement tool of any kind. We secured Lou’s life rights; we only used words written by Lou himself; we hired an actor to deliver those words; we used real footage of Lou in order to capture his true mannerisms and body language; and we hired AI experts from MIT Media Lab, Pinscreen, and Resemble AI to execute our vision.”

Johnson went on to state that the AI-altered footage helped establish Pearlman’s subjective reality, which evoked a contrast to what his victims experienced, calling this juxtaposition “essential to understanding Lou as a human being as well as a devious con man.” Although the intention here seems sincere enough, the introduction of generative AI to alter existing footage and simulate a conversation — which could have been easily conveyed via quoted narration or dramatized re-enactment — feels like a major misstep.

Moreover, this is not the first time a Netflix true-crime docuseries has used AI to evoke an intended effect, setting a disturbing trend that jeopardizes the ethics of credibility while creating a distorted picture of truth within a medium that has always aimed to distill it. The subjectivity of truth can only be transmuted into objective verdicts with verified evidence and corroborated testimonies, and the presence of generative AI creates a slippery slope for a worrying filmmaking practice to take root.