This post made me go down the rabbit hole, I needed to know the truth and this is what I found.

Russia NEVER had black slaves nor did the country create a market to trade black people. Russia NEVER participated in the Berlin conference to share Africa like some piece of meat. Russia NEVER colonized, underdeveloped, and looted Africa’s resources. Russia NEVER enabled a safety net for African leaders to hide stolen funds, use these stolen funds to develop themselves, and then grant the same funds back to Africa as loans. Russia never invaded and destabilized any African country, those who did the aforementioned are the ones pushing the narrative that “Russia” has become the Boogeyman… Those who colonized and for about 100 years refused to share their technology with Africa want Africa to be like those they like and hate those they hate. Nah! Never again! If Russia is the Boogeyman, then the west is the devil himself

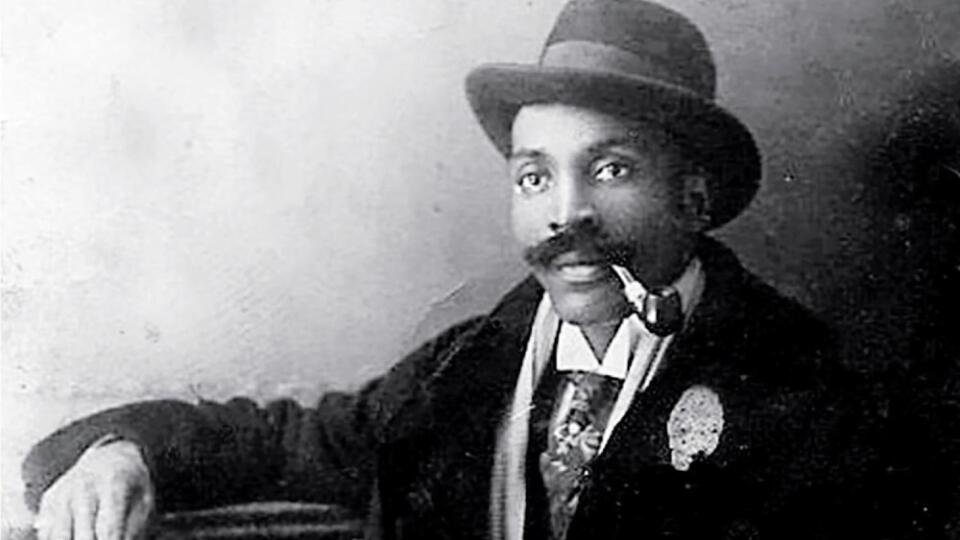

On Wednesday, March 10, at 3:30 p.m. join the Russian Area Studies program for “The Black Russian: How the Son of Mississippi Slaves Became a Millionaire in Moscow and the Sultan of Jazz in Constantinople” lecture by Dr. Vladimir Alexandrov, B. E. Bensinger Professor Emeritus, Slavic Languages and Literatures, Yale University. Co-sponsored by CLAS Dean, Africana Studies and the History Department

The book received numerous awards. I was preparing Alexander was a popular singer. I was in Constantinople and sang at a Black Russian club which took Author down the rabbit hole. He went to the National Archives USA and Fredrick Bruce Thomas was the owner of Constantinople. His father bought 200 acres for 20 dollars. 1870 5000 dollars in 1870. Very few cotton, corn and lumber businesses. Went from 200 acres to 600 acres African Methodist Church the second one. His stepmother was able to read and build a business. The rich white landowner wanted their land and they took this man to court and sold a lot of property to a lawyer to fight his father was killed by the tenant. Intervened in a Domestic fight and his tenant killed him. Thomas became a waiter in Chicago. Brooklyn was his next stop for very few black people in the north. He was a good waiter and valet and the head bellboy he had a passion for singing.

Color line in America and he went to London to pursue his music, English, Italy, French, German and he spoke these languages and this really interesting, Caught the Eye of a nobleman. They took him to Russia only a dozen black men in Russia, Jimmy Winkmen Jockey won the Kentucky derby. He was successful at his Job that Russian Aquarium was Disney for adults in 1911 they had 1 million dollars after the first year. Listen to the story below. He married his nanny and he married, Jacks Johnson and it was an exhibition boxing match. Thomas was not allowed because 1914 war. 10 million in property in Russia he had to leave it when the war started. So the soldiers wanted wine women and song. He struggled a bit he came out of his depts. He had trouble with Americans they would not help him. He did not get citizenship in America they did not want him in America. Racists did not want to deal with black Americans with white wives and mixed children. So racist America, Thomas became rich again in turkey Thomas had no citizenship at all.

Slavery is a tie that binds blacks and dissidents in pre-revolution Russia

In the mid-19th century, when the United States was still deeply involved in the slave trade, Russia was becoming a safer destination for black emigrants. Black writers such as Nancy Prince and Nicholas Said and black actor Ira Aldridge, who were vocal about their experiences there, helped lay the foundation for communism’s early appeal among black Americans, said Jessie Dunbar, Ph.D., assistant professor of English.

Prince, Said, and Aldridge and their words about Russian tolerance for black people likely led blacks in 19th century America to be more receptive to communist ideas, said Dunbar, who explores that influence in her forthcoming book, “Democracy, Diaspora, and Disillusionment: Black Itinerancy and the Propaganda Wars.”

“Twentieth-century black writers such as Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, and Ralph Ellison were certainly influenced by 19th-century Russian writers, but we need to investigate further back and ask why black people [in America] were so open to communist rhetoric,” Dunbar said. “It wasn’t just because of the rhetoric itself, but because there was already the foundation laid for having a certain level of respect for Russians. They didn’t participate in the American slave trade, and they had black heroes that they weren’t ashamed of — something that would take another hundred years for the U.S. to do.”

The first example

What Dunbar calls “ground zero” for this influence can be traced back to the rule of Peter the Great, who ruled Russia as its emperor and first czar from 1682 to 1725. Peter was desperate to convince western Europe to rethink its notions of Russia as a backward country and the idea that people are “born into royalty.” Essentially, Dunbar said, he believed everyone should start at the same point, only advancing if they contribute to society.

To prove this, the czar acquired a young African boy named Abram Gannibal, the son of a minor prince or chief, and raised him in his court as his godson. Gannibal was educated in the arts, science, and warfare, becoming fluent in several languages. He later joined the French Army to learn military engineering.

“It’s obviously terribly racist, but his point was to say, ‘If this black person from ‘savage Africa’ could start off as a slave and become a dignitary, obviously it could work out for everyone else,’” Dunbar said.

Even today, there are statues throughout Russia of Gannibal and his great-grandson, famed Russian poet, playwright, and novelist Alexander Pushkin, one of the first black Russian writers and who consistently expressed pride in his African ancestry. Seeing Gannibal’s and Pushkin’s prominence in Russia would have had a profound effect on blacks emigrating to Russia in the 1800s, Dunbar said.

“Black people coming to Russia from the U.S. would have been blown away by this — that they’d have a bust of a black man and that he was spoken about so favorably,” she said.

The beginnings of revolution

Dunbar’s research focuses on the ways in which Nancy Prince, Nicholas Said, and Ira Aldridge were influenced by the political stirrings in Russia in the 1800s and how they influenced American politics upon returning to the United States.

| “In a lot of ways, Nancy Prince became radicalized in a way that anticipates both [American] blacks’ interest in communism and also what’s going to happen in Russia later.” |

In 1825, a year after Prince’s arrival, members of the Russian army leads around 3,000 soldiers in a protest against Tsar Nicholas I’s assumption of the throne after his brother Constantine abdicated. Dunbar said the Decembrist revolt, as it would become known for the month in which it took place, is one of the first indications of Russia’s road to becoming a communist state following the 1917 Russian Revolution and an influence on Prince’s politics.

When Prince returns to the United States in the 1850s, she is treated horribly, despite the status she achieved in Russia. She joins the abolitionist movement and begins writing about her time in Russia. Dunbar said Prince is both honest and factual about how much better she is treated in Russia, while also being careful to criticize the Russian people for what she calls their “licentiousness.” In Prince’s opinion, the Russians gamble, drink, and dance too much; however, the impression Russian society leaves on Prince is a lasting one, Dunbar added.

“In a lot of ways, Nancy Prince became radicalized in a way that anticipates both [American] blacks’ interest in communism and also what’s going to happen in Russia later,” Dunbar said.

From prince to soldier

His new captors took him to Russia around the 1840s, where he was freed upon entry because Russia did not participate in the African slave trade, Dunbar said. Said took a job as a valet, and because having black servants were in fashion, he had more money and power than the Russian serfs, Dunbar said. Said stayed in Russia about a decade before choosing to return to his homeland, but decided on a whim at the docks to travel to the United States instead.

In America, Said struggled to find work, Dunbar said, mostly because of his aversion to manual labor. He later moved to the Southeast — settling at one point in St. Stephens, Alabama, according to “The Autobiography of Nicholas Said, A Native of Bourne, Eastern Soudan [sic], Central Africa” — where he was employed to open a school for black children. Few enrolled because educating black people was not well-accepted in the mid-1800s American South. “Openly receiving education was dangerous,” Dunbar said.

Said, who ultimately enlisted as a soldier in the Union army, later wrote that, while in Russia, he thought extensively about European encroachment on Africa and was inspired to return home.

“He said he wanted to be of use to his people,” Dunbar said. “It seems this kind of revolutionary thought process is what impacted his decision to fight in the Civil War. If he couldn’t be useful to black people by educating them, he would fight in the war instead.”

Curtain calling

“When he gets to Poland and Russia, his reviews are amazing, and in fact, he’s getting awards for his talent,” Dunbar said.

As Aldridge’s troupe moves eastward through Europe, the favorable reception to his work emboldens him to be more vocal about his issues with racism and slavery, Dunbar said. He begins speaking more boldly during his curtain calls about the travesty of American slavery, and he even attends secret — and illegal — leftist meetings in Russia, where he discusses correlations between American slavery and Russian despotism.

“You can see how he was being radicalized in Russia,” Dunbar said.

A readiness to change

Aldridge wasn’t the only Russian artist drawing correlations between slavery in the United States and the treatment of Russian people by their monarchy. By the late 18th century and through the 19th century, Russian nonfiction authors and essayists were writing extensively about American slavery because “it was the only way they could write about despotism without being sent to Siberia,” Dunbar said. For example, Russian author and social critic Alexander Radishchev’s depiction of the country’s socio-economic conditions in his 1790 book “Journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow” earned him exile to Siberia until 1797. Prince, Said, and Aldridge lived in Russia shortly after or during the time these works were being published, and the influence on their politics — and ultimately the politics of black Americans in the United States — is easily seen, Dunbar said.

| “… seemingly disparate groups of people are moving in lockstep politically in terms of expectations for their governments and what they think might work, well before communism occurs.” |

“It explains why both these seemingly disparate groups of people are moving in lockstep politically in terms of expectations for their governments and what they think might work, well before communism occurs,” she said.

As Russia inched closer to its own revolution in the decades after Prince, Said, and Aldridge departed, the country became less hospitable for black people. Money and jobs were scarce, and Russians were wary and resentful of sharing, Dunbar said.

“People were exceedingly poor, so the last thing they wanted to do was share what little they had with outsiders, and black people were the clearest outsiders,” she said.

Outside Russia, however, proponents of the communist movement were interested in converting black Americans to their cause.

“They wanted it to spread, so they thought, ‘This is the weakest link within the United States,’ – or strongest, depending on your perspective,” Dunbar said. “[They thought,] ‘They are the ones who would benefit most from altering the government.’”

This theory proved true in Birmingham, Alabama, where the Communist Party USA established a headquarters in the early 20th century and gained a foothold during the Great Depression. History Ph.D. candidate Kimberly St. Julian-Varnon’s interest in all things Russian started with a childhood illness. It forced her to stay home from fifth grade for a few weeks at her family’s farm in the rural southwest Texas community of Dayton, a population of about 7,000. “To pass the time I watched this eight-hour miniseries on the History Channel called ‘Russia, Land of the Czars’ and it blew my mind,” she says. “In sixth grade, I was the only student in my little middle school to do a book report on someone who wasn’t American: I did mine on Joseph Stalin.” And so, a Russian historian was born. Her current research in the School of Arts & Sciences revolves around how the African American experience in the Soviet Union shaped the Black identity and how the presence of people of color shaped ideas and understandings of race, ethnicity, and nationality policy in the Soviet Union post-Soviet space.

Penn Today talked with St. Julian-Varnon to find out more about her research, how these seemingly disparate notions of race in Russia and the United States are connected, and a few surprising discoveries.

What does your research involve?

I am looking at how race functions and how people understand race in the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc. My project looks at how Soviet residents understood Black visitors and what they understood about race. The Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc were officially ‘raceless’ places; they didn’t recognize race, and you couldn’t identify as a race. How does race function in a place that says race is not a category?

How did you become interested in this course of study?

Ever since my sixth-grade report on Stalin, Russia has been a part of my life, but I never studied it until I started my undergrad at Swarthmore. My first history course in college was called ‘Angels of Death: Russia under Lenin and Stalin,’ and I fell in love with everything Russian and the Soviet Union. I did my master’s at Harvard in Russian, Eastern European, and Central Asian Studies. In the summer of 2013, I went to Ukraine to do archival research, and that is where it hit me. I was the only Black person most people there had ever seen before. When I was there, I met an Afro-Ukrainian woman. We didn’t know each other, but one day we just saw each other in the street, stopped and hugged each other. And she was like, ‘What are you doing here?’ and I asked the same of her and she told me she was Ukrainian. That’s where the kernel of my research idea came from. I wanted to know whether there were other people like me who came to the Soviet Union. I wanted to explore these stories that very few people know about the diaspora in Eastern Europe.

Much of my earlier work has looked at the African American experience. A paper I just finished for Dr. Daniel Richter for a first-year seminar looked at how African American visitors to Soviet Central Asia in the 1930s racialized Uzbeks as Black people, and they developed these ideas of racial solidarity with them. What I’m really interested in now is to understand how Soviet people and Eastern Europeans understood Blackness and race. So, I’m kind of flipping it over.

To the casual observer, it might seem like race relations in the U.S., Russia, and Ukraine would have very little overlap. What are the links you’ve found?

There are a lot of interesting connections between Russia, America, and race, even going back to the imperial period in Russian history when Russians were paying attention to slavery in the United States. You also had people who were descendants of slaves in the U.S. who went to live in pre-revolutionary Russia. During the Soviet period is when you start seeing African American artists like Langston Hughes and Paul Robeson go to the Soviet Union, but the Soviets themselves in the early 1930s were recruiting American workers, and they recruited African American agricultural and industrial specialists to help them build the Soviet project.

There was heavy Soviet interest in American race relations, particularly for Lenin and Trotsky in the ‘20s; they were looking at Jim Crow America, and they were producing propaganda showing how racist the United States was. There was a lot of interest in African Americans as an oppressed people but also as oppressed workers.

Here’s one interesting connection from the 1930s. An African American woman’s son had disappeared, and then she received a letter from him saying he was in Moscow and she should join him because there were so many jobs. She picked up, left New York, and moved to Moscow. In 1936, a famous Stalinist film came out called ‘Tsirk,’ or ‘Circus,’ and the plot involves an American actress who runs to the Soviet Union and she’s hiding some terrible secret. She has an evil German manager who is always threatening to reveal her secret and eventually he does, and that secret is that she had a Black son. But the baby is embraced by all the Soviet community in the film, showing how welcoming they are to all people. That little baby actor is an Afro-Russian, and his grandmother was the woman who took the boat from New York to Moscow to find work. The baby’s name is James Lloydovich Patterson. He’s still alive and is a famous Afro-Russian poet and actor. His father stayed in the Soviet Union and was a radio presenter during the war and was killed when the Germans bombed the building he was working in. It’s so interesting to me that all this comes from these two people during the Jim Crow era who thought, ‘America’s not great. What could Russia offer us? It couldn’t be any worse.’

In the Cold War and into the ‘60s and ‘70s, the Soviets were trying to influence newly independent African states, and they were using what was happening in the United States and the treatment of African Americans to say, ‘Do you really want to align with the United States considering how they treat people who look just like you?’

In 2016, we had Russia using different race issues in the United States to make these fake Facebook accounts and take out big ads. What Russia is doing now is not new in terms of inflaming racial issues and bringing those to the forefront. Even in the 1960s, the United States knew that race relation were a security problem because it could be exploited.

Why is it important to study how African Americans experienced the Soviet Union?

American race relations tend to define how race is understood around the world. When people like me go to Eastern Europe and we run into a skinhead or are told not to go out at night for our safety, people there will say, ‘Oh, that’s just xenophobia, it’s not because you’re Black.’ Or they’ll say, ‘We can’t be racist; we didn’t have slavery.’ I want to understand how Russia and Ukraine went from being a beacon for African Americans and Africans in the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s to a place where if you have dark skin you can’t go out at night.

I want to show that race functions on different levels. A long-term goal of mine is to be able to be an expert witness in asylum cases for like Afro-Russians and Ukrainians who are seeking asylum. It’s happened before that they can’t get asylum because people think there’s no race problem in Russia.

What is the most surprising thing you’ve come upon during your years of research into this topic?

The most famous American visitors to the Soviet Union were Langston Hughes and Paul Robeson. But there was a group of Black agricultural specialists recruited from Tuskegee Institute and they went to Soviet Uzbekistan. One of them was Joseph Roane who was from a small town in Virginia called Kremlin, if you can believe it, and he helped Uzbeks improve cotton production. He and his wife had a baby there and named him Yosif Stalin Roane, and they eventually moved back to the U.S.

Those are the things that stand out to me, and those are the voices I want to show: voices of regular people who just took a chance.

What is the most important thing for people to understand about this topic and your research?

To paraphrase a Stephen King quote, ‘Go then. There are other worlds than these.’ That’s what draws me to the Soviet Union, especially in the 1920s and 1930s. There were so many terrible things that happened in the Soviet Union then, but there were these little pockets of time where people were thinking about remaking the world. I find it fascinating that that’s something these African American travelers got to do there: to help remake the world.