In a recent talk at the British Museum (BM), sitting between the two great Assyrian lamassu from Khorsabad, the Turkish writer Elif Shafak spoke about the role fiction can play in shedding light on otherwise forgotten moments of personal and historical trauma. Shafak’s recent novel There Are Rivers in the Sky explores questions of museum collecting through the story of the acquisition, by the BM, of remains from Nineveh, and the discovery of Assyrian culture thanks to George Smith (“King Arthur of the Slums and Sewers” in Shafak’s story), who decoded the cuneiform held at the museum, and discovered and translated into English The Epic of Gilgamesh. Shafak intertwines this story with that of two contemporary women, one of whom is a young Yazidi who experiences the genocide by Islamic State (Isis) of the Yazidi people on Mount Sinjar in 2014.

The Assyrian collection at the BM is largely the result of excavations by the 19th-century archaeologist Austen Henry Layard (whose 1849 book, Nineveh and its Remains: With an Account of a Visit to the Chaldaean Christians of Kurdistan, and the Yezidis, or Devil-Worshippers; and an Enquiry into the Manners and Arts of the Ancient Assyrians, plays a central part in Shafak’s novel). It is justly famous, heralded by the great lamassu from Khorsabad, despite being crammed into claustrophobic galleries in between Ancient Egypt and the Parthenon sculptures.

A poignant absence

Evidence of the other cultures mentioned in the title of Layard’s book, the Chaldaeans and the Yezidis (an alternative spelling of Yazidi), is much harder to find. The Yazidi people, in particular, are virtually invisible in museums in the West, an absence all the more poignant in light of their recent history.

Following the massacre of 2014, some 200,000 Yazidis still live in refugee camps in Kurdistan, unable to return to their destroyed homes. Hundreds of the women and children who were abducted and enslaved by Isis are still missing. Although many of the Yazidi shrines have been reconstructed, living Yazidi culture remains in a fragile state.

Museums in Iraqi Kurdistan are reported to be collecting Yazidi artefacts, notably the Slemani Museum in Sulaymaniyah, as well as the Ethnographic Museum at the Erbil Citadel, according to Sébastien Rey, the BM’s curator for Ancient Mesopotamia.

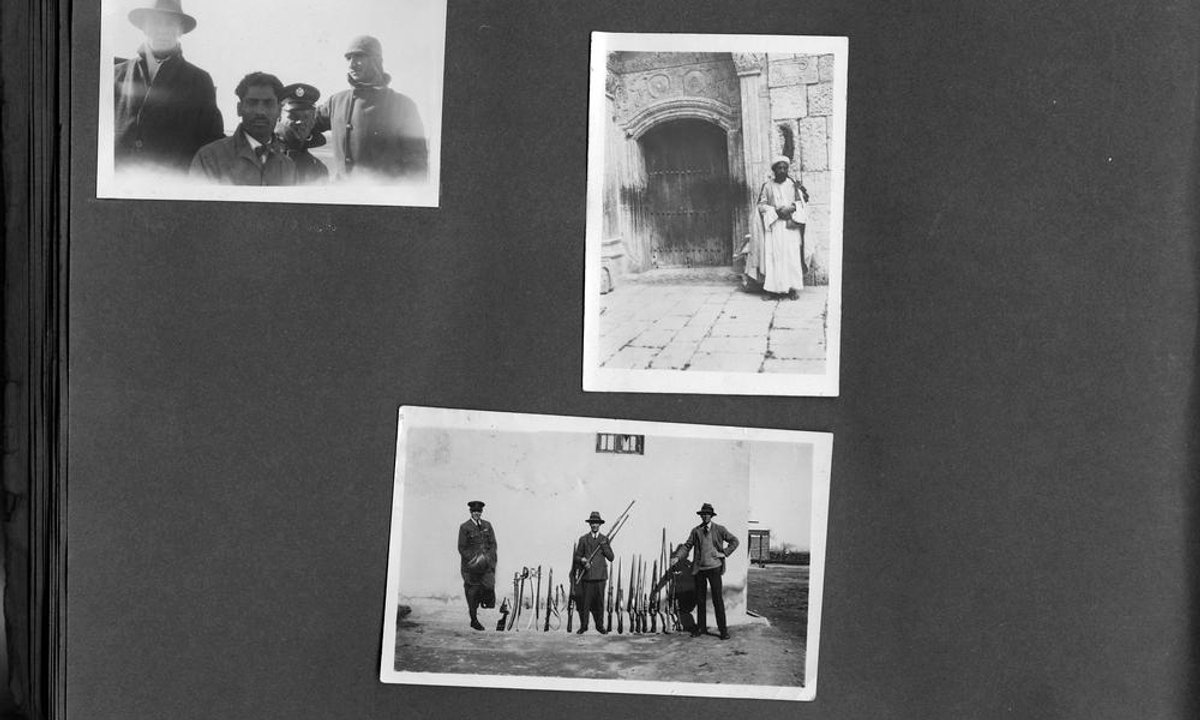

Outside of the Kurdish region it is a different story. A search on the BM database brings up a sole item, a photograph of a Yazidi man standing in front of the shrine of Shaikh ‘Adi ibn Mosāfer. It comes from the page of an album donated to the museum in 2012.

Noorah Al-Gailani, the curator of Islamic Collections at the BM, also points to two 18th-century drawings of Yazidis, and a Safavid metalwork peacock, that may well have been used by the Yazidi to represent Melek Taûs, the “Peacock Angel”. The lack of Yazidi material, Al-Gailani says, can in part be explained by the closed nature of the Yazidi community. When Layard wrote of his time with the Yazidis, he found them “naturally suspicious of strangers, and fearful of betraying the secrets of their faith”, an understandable characteristic in the face of a long history of persecution.

Historically, museum collections of artefacts from the Near East have not been acquired with the intention of representing minority groups, but rather acquired piecemeal and on the basis of individual interest—and naturally the spectacular nature of the finds from Nineveh, Nimrud and Khorsabad drew the attention more than artefacts from the Yazidi, or other ethnic-religious groups such as the Mandeans or the Arab Jews.

Any project collecting evidence of Yazidi material culture should begin with how the Yazidi represent themselves, suggests Paul Collins, the assistant keeper in the department of Middle East at the BM. The first answer to this question from the Yazidi is of course unlikely to be “by artefacts on display in the British Museum”—displays that very few Yazidis would have the opportunity to see for themselves. A richer form of identification might be given by intangible heritage—music, food, storytelling, the sort of thing that cannot be collected and preserved by museums and might for those thousands of Yazidis still living in refugee camps and away from their still ruined homeland of Sinjar be the most meaningful carrier of their tradition and culture.

Compared with the urgent ongoing need for humanitarian aid and political representation, museum collecting might seem a trivial issue. The BM in particular has little ethical credibility left in the light of its renewed sponsorship deal with the oil company BP, which recently announced the development of new oil and gas fields in Kirkuk, Iraq. And yet with their powerful cultural and political reach, museums have a moral duty for such representation.

• John-Paul Stonard is an art historian and author