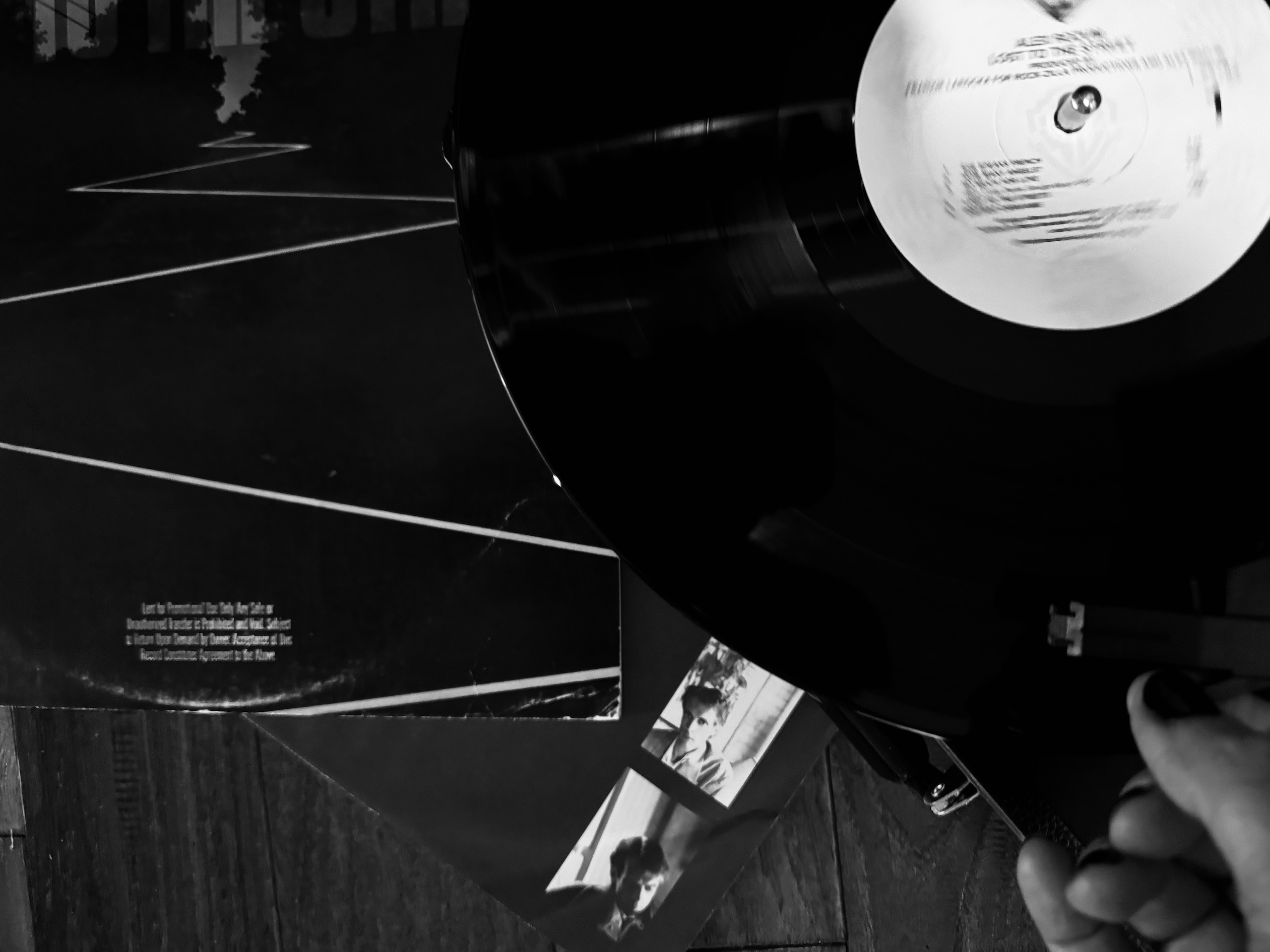

As befits its title, Lost to the Street, Alex Rozum’s debut album disappeared almost immediately after it was released three-dozen years ago this month, in September 1988. I haven’t owned a copy since Bill Clinton was president. Yet its songs still find their way into my head to this day.

To be sure, Lost to the Street is plenty tuneful in a post-Roxy Music Bryan Ferry sort of way. Rozum’s songwriting and voice are surprisingly assured for a rookie, and he’s supported by skilled session players and polished production. Perhaps the music is a bit slick, at times a little schmaltzy, but you could say the same of Bryan Ferry. Yet despite the lush romanticism and sonic fullness of Lost to the Street, there’s something oddly slight about it.

More from Spin:

- Linkin Park Unveil New Song, Expand Tour

- James’ Tim Booth Talks U.K. No. 1 Album, Touring With Johnny Marr

- For Cowboy Killer, It’s All About ‘the Love’ and ‘the Flowers’

So why is this album still with me? Why, on my favorite song, “Don’t Look Directly Into the Sun” (lamentably the album’s lone CD-only track) does its cautionary title, and his admonition that “you’ve got potential but no discipline,” sound like a dire, even mortal warning from an old soothsayer? Why, despite the album’s peculiar staying power, did Rozum never make another one? And why, when I searched online, did I find no trace of his existence outside of Lost to the Street? In the Internet age, no one disappears altogether.

Unless they were dead before it started.

“Alex had a rare form of cancer,” says his older brother Tom Rozum, also a musician—an illustrious bluegrass mandolinist (he plays on one of the tracks on Lost to the Street). The sarcoma was ravaging Alex during the recording sessions. He died about two months after the album’s release.

That’s why Lost to the Street feels slight. It’s the sound of a man turning into a ghost.

Alex was born in 1955 in Connecticut. He and Tom were self-taught musicians. Tom played guitar, Alex keyboards. They spent hours playing music in their basement, mostly English rock. “We were heavily into the Kinks in the late ‘60s,” Tom says, making a comparison to Dave and Ray Davies as his voice quavers with emotion over his late brother.

Tumors first showed up when Alex was in middle school. Treatment eliminated them, but later, when Alex was studying for a fine art degree at Connecticut College, they came back. This time they required surgery and chemo.

Alex recovered again. After graduating, he moved to New York City with a printmaking degree (the cover art on Lost to the Street is his), but he wanted to do music too. Tom had a close musician friend who lived in New York City with his wife. Her name was Laurie Manifold. She’s credited as Alex’s co-writer on Lost to the Street. I tracked her down in Arizona, where she’s a painter.

“When I met Alex, he was 18 and still in high school,” Laurie tells me. “He was very charismatic and charming and mysterious, much better looking in person than in photographs, which never did him justice. So many people—girls and boys—would throw themselves at him. After he died, all these people came out of the woodwork to say he was the love of their life. He needed somebody to protect him. Once he got to New York, I became his guardian dragon.”

Alex moved into the Upper East Side apartment Laurie shared with her husband, who had a piano and a reel-to-reel recorder. Alex and Laurie would sit riffing on lyrics together while he noodled on the piano. These cocktail-lounge improvs started turning into real songs.

Meanwhile, they’d go out clubbing. A favorite hangout was Tribeca’s ultra-hip Mudd Club (namechecked in Talking Heads’ iconic “Life During Wartime”). Ray Davies was living in New York at the time, so they were able to see a lot of Kinks shows. Alex also got into T. Rex. A cover of “Chrome Sitar” would wind up on Lost to the Street.

Alex was steeping himself in New York’s music scene, but he was too insecure about his musicianship and his singing to play in public. But he had songs and ambition. “He wanted to be famous,” Laurie says.

He found an ingenious way to get a record deal. There was an upscale florist in Laurie’s neighborhood called Persephone’s. Alex charmed his way into a job there—not because he wanted to do floral arrangements, although his art background made him a natural (“He was remarkable with flowers,” Tom says). He wanted to deliver them.

“He would take flowers to fancy parties and then get himself invited,” Laurie says. “He had this amazing thrift store wardrobe. He did flowers for Whoopi Goldberg and Oprah’s events for The Color Purple, and so he went to the premiere and afterparty.”

There was also at least one brush with musical royalty. Persephone’s had a standing order with John and Yoko. Alex regularly delivered their flowers to the Dakota. Yoko once threw a fit over an arrangement of all-white poinsettias because one had a splotch of red on it. “She said it looked like blood,” Laurie says. John’s tapes were usually lying around. “Alex really wanted to take some of them, but the only thing he ever took was a pencil that had John’s teeth marks in it.”

When Warner Brothers called Persephone’s about a party in the Hamptons, Alex showed up in his thrift store wardrobe with the flowers—and his demo tape, which he managed to get into the hands of an A&R executive. And just like that, this unknown from small-town Connecticut, who had never been in a band or a recording studio in his life, had a major-label record deal.

“When he called me and told me Warner Brothers was going to sign him,” Laurie says, “I thought he was joking.”

Right after they signed him, the cancer came back. Alex sat Laurie down and told her it was inoperable. Then he never mentioned it again. He went into the studio with only a few months to live.

“Alex was really ill. He looked like a ghost, with sunken eyes and a distended belly from medical treatment,” remembers Rob Mathes, a longtime session player who contributed guitar and keyboards to several tracks on Lost to the Street. “This was clearly a final work, a goodbye of sorts”—a strange quality for a debut.

Industry veteran Frankie LaRocka was Rozum’s producer-by-assignment, but Mathes says Lost to the Street “was a love project for Frankie,” who treated it like a baby left at his front door. He took the love project upstate from Manhattan to Mamaroneck, where his colleague Peter Denenberg had a studio called Acme. They often worked together. Shortly after recording Lost to the Street, they broke big as part of Spin Doctors’ early production team.

LaRocka died in 2005, but Denenberg still has a thriving production business—he’s a regular recording partner to Deep Purple bassist Roger Glover—and is Department Chair of the studio production and composition programs at SUNY Purchase, not far from Mamaroneck.

“Alex was a little wide-eyed at the whole [recording] process and all the people,” Denenberg says, “He was quiet, sweet, and polite, but also clear and eloquent—and he knew what he wanted his music to sound like. He was not just sitting there letting other people do it.” Alex is co-credited with LaRocka as Lost to the Street’s producer and arranger.

Laurie Manifold has bleak memories from a visit she made to the studio during sessions. “It was agony, absolutely horrifying,” she says, “This was his dream, and the studio guys were great with him, but he looked like hell, and it was hard for him to sing at all. He’d say, ‘I don’t know how many times I can sing this, so you’d better record now.’”

LaRocka and Denenberg had assembled an Acme house band of sorts from their musical circle (including Mathes, who still lives and works as a musician in the area). Many are still in touch, like a family. One, Billy Masters, is now a producer in Austin, Texas.

“I still get emotional just thinking about Alex,” he says. “It was understood that he was ill. That was a heavy thing, and I was only in my 20s, so that made it even heavier. But Alex had a gentle, beautiful light about him. I don’t think I was quite conscious of that energy at the time, but it made us all step up to the plate in a way that honored it.”

Billy still listens to Lost to the Street sometimes, less to hear his guitar parts than Alex’s singing. “His voice is very haunting,” Billy says, “and extremely smooth. He wasn’t belting. It’s real emotion, real stuff. He reminds me of that other New York guy who came right after Alex and died young.”

Jeff Buckley?

“Yeah, that’s it.”

Alex and Laurie co-wrote Lost to the Street’s lyrics over a span of several years while his cancer was in remission, but Alex’s tender, almost tenebrous delivery turns them into a departing soul’s last words. His weary desperation is audible in the propulsive but pensive “How Many Angels?”; the poignant, resigned “In Our Dreams”; and the Elton John-worthy “Somewhere,” of which engineer Denenberg says, “I get choked up on the first line of that song: ‘Sometimes I have had to wonder / Just where I’m going to?’”

By the time Lost to the Street came out in September 1988, the ailing Alex had moved out of New York and back to his parents’ house in Connecticut. “One of the last things he was able to do was drive us around listening to a tape of the finished product in the car,” Laurie says. “Right before Thanksgiving I saw him again, and it was really shocking. If my husband hadn’t been behind me, I might have fainted. But Alex still wouldn’t talk about it. As long as I didn’t say anything, everything was okay.”

Alex died two days before Thanksgiving. So many music industry people showed up at the memorial service that Laurie and her husband had no place to sit.

“There were people who really believed he was magical somehow,” Laurie says. “I think all he really wanted was to have already been famous, so he could walk into any bar in New York City and just sit down and start playing the piano.”

The ghost of a star who never got a chance to shine, serenading the living from beyond the grave.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.