What would happen if Raymond Chandler and H.P. Lovecraft wrote a novel together? Comic series “Fatale” by Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips offers an answer. Published from 2012 to 2014 across 24 issues at Image Comics, “Fatale” is named for the archetype every film noir needs: the femme fatale, the sultry knockout who wraps men around her fingers without a care for what happens to their twisted forms (phallic cigarette optional).

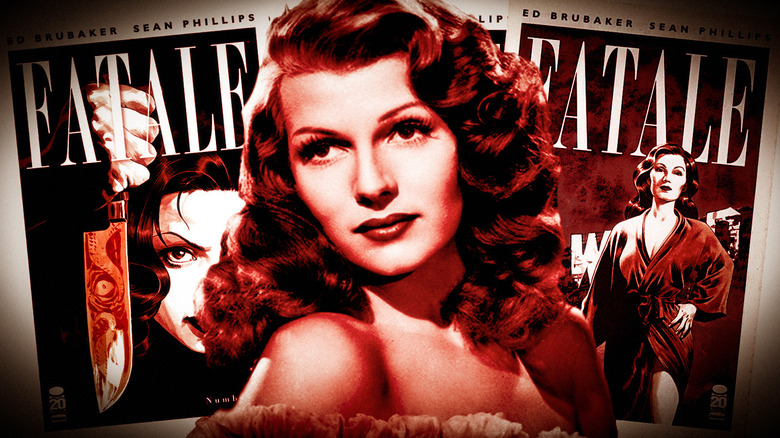

The center of “Fatale” is one such woman, named Josephine or simply Jo. Colorists David Stewart and Elizabeth Breitweiser give her blood red lips and hair as black as Ava Gardner. Is her raven hair the same shade as her heart? Not quite. You see, Jo simply can’t help making men desire and chase after her — especially men who want her for an occult sacrifice. Brubaker and Phillips mostly cook their comics hardboiled, such as “Criminal” (soon to be a Prime Video TV series) and their new “Reckless” graphic novels. In “Fatale,” they use their familiarity with the noir genre branch out, combining a pulpy mystery with supernatural horror.

A common motif in “Fatale” is tentacles (Cthulhu who?) and that image embodies the comic’s genre cocktail. Those slimy green tendrils represent not just the dark gods worshiped by the evil priest Bishop, but Jo’s invisible control that every man who meets her gaze walks into.

Horror and noir make for an elegant blend, and not just because of the comic’s craftsmanship. Noir and horror are one of the most seamless genre combinations out there. “Fatale” — rereleased in full this past July as a new compendium edition — is just one example that shows why.

Why film noir and horror movies blend together so well

Film noir goes back to Old Hollywood, and most of the genre’s classics are from that era. In the 1940s, studios often adapted pulp detective or crime novels. Though often lumped together, there are two common noir plots. Either a detective character discovers a larger conspiracy in what seemed like a simple case (“The Big Sleep,” “The Maltese Falcon,” etc.) or an everyman is dragged into the world of crime, whether by choice or bad luck (“Double Indemnity,” “Detour,” etc.) Both formulas leave room for a beautiful woman stringing the lead along.

The black and white photography of these crime pictures became as synonymous with them as the sardonic private investigators and duplicitous dames. Italian-French film critic Nino Frank is considered the one who coined “film noir” (“noir” meaning “black” in French) to refer to movies of this type. It’s a choice that stuck because noir evokes not just the pictures’ coloring, but their cynicism too.

Noir and horror may not typically share character archetypes, but they have common moods. Both employ mystery: noir for suspense and horror for fear, for the unknown is the scariest thing of all. That’s why so many horror movies use the same strong contrasts of bright light and dark shadow; you can’t see in the dark, and something evil could be lurking in there.

Building on the chiaroscuro style in traditional art, this use of darkness in film goes back to the German Expressionist artistic movement, and was most famously realized on film in the early horror film “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.”

The best horror/noir hybrid films

As horror and noir draw from a common artistic root, some films of either genre blur lines. Take Charles Laughton’s 1955 film “The Night of the Hunter” (pictured above), a Southern Gothic picture about a serial killer disguised as a preacher in Great Depression-era Appalachia. It’s undoubtedly a horror film, but because of how cinematographer Stanley Cortez extensively used shadows, “The Night of the Hunter” is sometimes called a noir despite its rural setting and child protagonists. Or Alfred Hitchcock’s “Psycho,” which begins as a crime picture and slowly morphs into a horror film once a serial killer enters the frame.

Serial killers especially are easy ways to bring these genres together. Such stories are often procedurals about law enforcement tracking the murderer — noir. But these stories reel you in with the promise of perverse violence, the kind that’s only fun to see vicariously onscreen — horror. It’s no wonder that so many serial killer pictures are both horror and detective films: “The Silence of the Lambs,” Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s “Cure,” and this year’s sleeper hit “Longlegs”

Author Megan Abbott, in her introductory essay “A Fatale Blow” in the new “Fatale” compendium, writes that, “Both noir and horror […] are driven in large part by the fear of monstrous women.” See Jacques Tourneur’s 1942 “Cat People,” about a European ingenue who terrorizes New York City by night with her suppressed other half (a feline monster). “Cat People” has been cited as another example of horror and noir meeting, and the way it uses both genres to tell a story about femininity being scary is just what “Fatale” did decades later.

“Fatale” understands how men can’t resist women’s power over them, a sensation that leaves them terrified. Issue #12 opens on a “witch” being burned at the stake in medieval France. That “witch” is Josephine’s predecessor in every way from the most to least literal.

Fatale acknowledges the noirs that came before it

“Fatale” opens with a funeral for writer Dominic H. Raines, one of Jo’s old flames. Attending the funeral is Raines’ godson, Nick Lash. A single conversation with Jo at that funeral makes him obsessed with her, especially when he finds an unpublished manuscript from Raines, armed men try to steal it, and he discovers that Jo may be far older than she looks.

Yes, Jo’s power doesn’t end at controlling men’s minds; she’s also immortal and unaging. The comic, using a non-chronological structure, documents a pattern across her long time on Earth: Jo enters a man’s life, attracts his obsession, and leaves him a wreck. “Fatale” doesn’t bog itself down in exposition but lets you read through the lines that Jo’s powers came from the same evil gods her pursuers worship. They want to sacrifice her because her powers make her all the more appetizing to their masters.

Abbott suggests that Jo’s eternal life is a representation of how the cruel seductress archetype endures across time and culture. The femme fatale has been with human civilization since its dawn — back then we called her Lilith and the Whore of Babylon. Since the 20th century, we’ve given her names like Gilda (in, well, “Gilda”), Kitty March (“Scarlet Street”), Raven Darkholme/Mystique (“X-Men”), and Ava Lord (Frank Miller’s noir comic “Sin City”).

Fatale is a comic about the horror of being a beautiful woman

Even Brubaker and Phillips once made a straightforward femme fatale noir. Volume 4 of “Criminal” — “Bad Night” — follows a down-on-his-luck cartoonist who falls for a lovely redhead named Iris, but discovers her only interest is in using him as a patsy. Brubaker writes in a 2015 essay afterword that with “Fatale,” he wanted to make a cliché into a character. “Think of [Jo] when you read fairy tales or watch movies from the ’40s and ’50s or hear tales of the girl sacrificed to the volcano…”

Jo’s supernatural qualities, the very thing which makes her unrealistic character, are also the key to her humanity. She’s not trying to ensnare men, but she can’t control the effect. She’s not so selfish that she toys with men for fun, but she’ll sometimes sacrifice them as a necessary evil. Better her than them.

The phrase “So beautiful, it’s a curse”? That is literally Jo’s existence. Men who see her want to possess her more so than love her, and some will act on that urge violently. Even the good ones can’t truly love her; she’s a walking fantasy girl to them, one they can never say no too. One can compare Jo to Marvel Comics villain The Purple Man (played by David Tennant as “Kilgrave” in “Jessica Jones”); if you hear his voice, you’re compelled to obey him. Instead of showing how terrifying such a person would be to others, “Fatale” is about how isolating it would be to have that power (unlike Kilgrave, Jo has a conscience).

Abbott writes that Brubaker succeeds in his goal of making his reader root for a femme fatale because, with Jo, he flips the usual noir villain into a noir hero, i.e. the scrappy anti-hero just trying to survive while on the run.

How horror films use color

I previously mentioned how noir and horror both use dark shadows. That said, it’d be dishonest to imply every horror film out there eschews bright colors. Sometimes, ostentatiousness can be scary as any long shot of a dark hallway. See Dario Argento’s giallo film “Suspiria,” or Hitchcock’s technicolor film noir “Vertigo.” The moment in the latter that feels most like a horror film is during Scottie’s (James Stewart) psychedelic dream sequence, where different colored flares flash across the screen, adding to the effect of the montage.

Brubaker has cited Hammer horror films as one of the inspirations of “Fatale.” Those films (mostly made in the late 1950s and then the 1960s) took the 1930s Universal horror films and remade them in technicolor instead of ghastly black-and-white. Hammer’s films feature lurid blood and nudity, as does “Fatale.” It’s one of Brubaker and Phillips’ bloodiest comics and the color red often pops up when the occult is afoot, whether as background coloring in a panel, robes, or good old blood splatters.

Having read most Brubaker/Phillips’ books, “Fatale” has some of the most experimental art in any of them. Especially the penultimate issue #23, featuring a “cosmic sex” scene between Jo and Nick when she lets him inside her soul.

Phillips is often conservative with page layout: square panels neatly aligned in rows, matching his realistic character designs and settings. In “Fatale,” he lets loose, using more collage style framing. It couldn’t be a more fitting choice for a series all about adding a dash of supernatural to lowkey pulp.

Ed Brubaker’s comics love all types of pulp

As Jo is undying, “Fatale” jumps around to different times, and in the process, different genres. It’s not quite an anthology because there’s a single framing device and characters that link each story but the series’ premise could sustain one. (Brubaker initially pitched “Fatale” as only 12 issues, but decided he needed more. You can feel the fun he’s having playing around with this world as you read.)

Volume 1, “Death Chases Me,” takes place in the 1950s and is a noir about police corruption a la “The Big Heat.” Volume 2, “The Devil’s Business,” jumps ahead to 1970s Hollywood, where Jo is a shut-in living in a huge old mansion. The influence of “Sunset Boulevard” is obvious, down to the story ending with a dead man lying face down in a pool.

Volume 3, “West of Hell,” is when Brubaker really lets loose, telling one-shot issues set in different points of history. Issue #11 sees Jo meet pulp writer Alfred Ravenscroft in 1930s Texas, whose stories resemble her dreams. Ravenscroft appears to be inspired by Robert E. Howard, creator of Conan the Barbarian — especially since issue #12 shifts to sword and sorcery, following a girl named Mathilda who had the same curse as Jo centuries ago. Issue #13 becomes a Western, then issue #14 becomes a World War 2 serial about occult Nazis (a la “Indiana Jones”).

Brubaker loves all types of pulp fiction, from superheroes to spy thrillers. His defining run on “Captain America” at Marvel Comics is about merging those two genres, just like “Fatale” does horror and noir. His and Phillips’ latest book, “Houses of the Unholy,” is a satanic panic detective thriller once more merging horror and mystery, just like “Fatale” did. It’s such a natural recipe that even pulp aesthetes like Brubaker and Phillips couldn’t resist trying it twice.

The new “Fatale” compendium edition is available from digital and physical retailers. The series has also been published in five paperback volumes and two “Deluxe” hardcover volumes.