[ad_1]

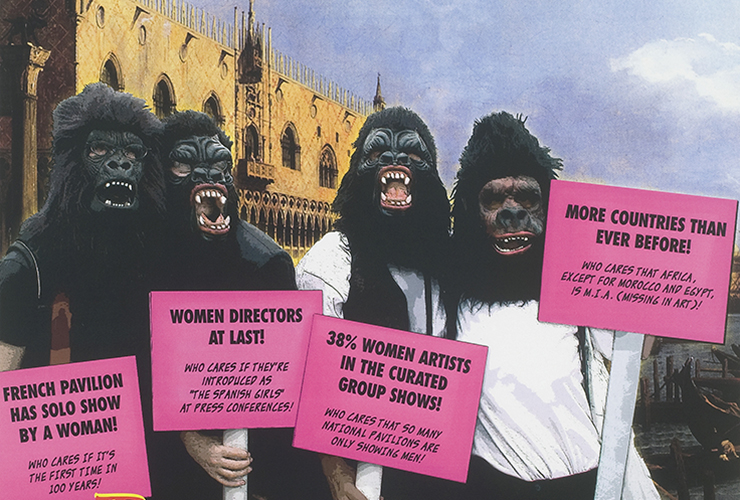

The founders of the movement and the other women artists who soon joined them wore gorilla masks in their public protests. To emphasize the collective nature of the movement, the identities of individual members were kept secret. As a spokesperson said, “We wanted the focus to be on the issues, not on our personalities or our own work.” Even the identities of spokespeople were kept secret; in addition to wearing their gorilla masks during news conferences, they adopted the names of famous deceased women artists. The secrecy of the group, which eventually grew to a high of about 30 members, was kept, adding an air of mystery to the protests. (There have been about 65 members over the years, with a handful still considered as members today.) A year after its founding, the Guerilla Girls broadened their cause to expose institutional racism, and women artists of color joined the movement.

I’ve sometimes wondered if Ellen Lanyon, an old friend who died in 2013 and about whom I have written in this blog, was among the founders of the Guerilla Girls. Born in 1926, she had certainly experienced her share of discrimination from artworld powers, and she was friends with many of the best-known female artists and feminist critics of the 1980s. But I never asked Ellen, and she didn’t volunteer the information.

Today, diversity and inclusion are the buzzwords for museums and other art institutions, so it might be assumed that the inequities highlighted by the Guerilla Girls almost 40 years ago are a thing of the past, but that is apparently not the case. According to Artnet News, a recent study of 350,000 works acquired by 31 American museums between 2008 and 2020 showed that works by women artists comprised only 11 percent of the acquisitions. For Black artists, the number was even worse: their works comprised only 2.2 percent of acquisitions and were included in only 6.3 percent of exhibitions.

In fairness to museums, it should be pointed out that many if not most of their acquisitions each year are donated, not purchased. If private collectors in the past century were unlikely to acquire artworks by women or persons of color, the pool of artworks available for donation to museums is going to be skewed toward works by white male artists. And no museum if offered a major painting by Claude Monet or Jackson Pollock is going to turn down the donation, explaining that they already have plenty of works by white males.

It is primarily by purchase of works of art by women and minorities that museums will be able to diversify their collections. As no museum in recorded history has ever complained about having too much money in its budget for acquisitions, the allocation of limited funds will need to prioritize the purchase of works by women and artists of color if injustices are to be rectified. Will such a policy lead to charges of reverse discrimination?

If just over 14 percent of the United States population self-identifies as Black, should 14 percent of all artworks purchased be by Black artists? Should a museum buying 50 works of contemporary art ensure that four of them are by Hispanic males and four by Hispanic females, as per current demographic data? What about gender and sexual preference? Should the artist’s being gay or transsexual factor into curators’ decisions? What about subject matter? If a museum has acquisition funds for only one Black artist, should it prioritize a realistic work that depicts Black life over an abstract work?

Here are two works done in the same decade by contemporary Black artists, the first by Sam Gilliam, a graduate of the University of Louisville who became a leading member of the Washington, D.C. group of artists who practiced what is now called the Color Field Painting. His artistic interests set him at odds with Black artists in the 1960s who advocated for art with a social message. He recalled Stokely Carmichael bringing him and several other Black artists together during this period to tell them, “You’re Black artists! I need you! But you won’t be able to make your pretty pictures anymore!” Gilliam, however, declined to change his style.

[ad_2]

Source link